Neither rain, nor snow, nor heat of summer, can stay Janet Draper from her appointed rounds

Betty Belanus takes a stroll down the garden path with self-professed “hort nerd” Janet Draper.

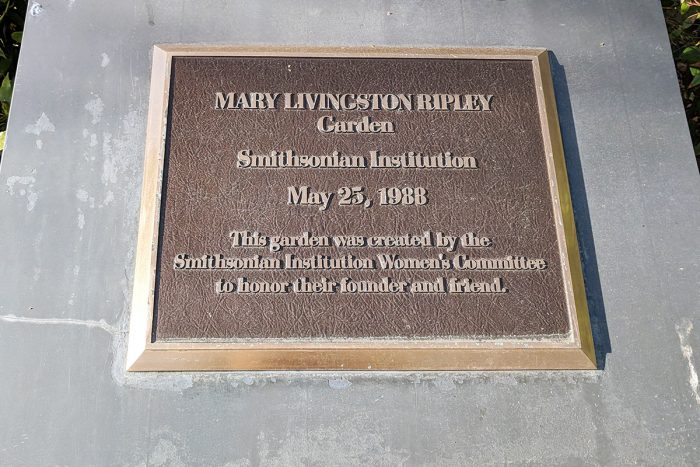

The Mary Livingston Ripley Garden, which winds its way between the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and the Arts and Industries Building, is a popular shortcut from our office to the National Mall. This garden not only has a name, but it also has its own lead horticulturalist and self-proclaimed “hort-nerd,” Janet Draper. As part of the staff at Smithsonian Gardens, she has been planning and tending this plot for the past twenty years.

The Mary Livington Ripley Garden is located between the Arts and Industries Building and the Hirshhorn Museum. (Photo by Betty Belanus)

To unlock the secrets of this oasis, we joined a daily tour of the garden, which Draper offers seasonally every Tuesday at 2 p.m. Several interested—and definitely better informed—members of the public joined the tour as well. Starting at the National Mall side of the garden and ending at Independence Avenue, Draper speaks of her plant choices as though she is the casting agent of a seasonal pageant. Some plants take the spotlight while others fill out the supporting cast, but she chooses each with care and an immense knowledge of how they play out their roles.

Janet Draper is the supervisory horticulturist for the Ripley Garden. (Photo by Betty Belanus)

Her description of one plant begins prosaically, veers into the sensual and poetic, and ends up firmly based in practicality:

“That’s one of our natives—a Midwestern prairie plant. It’s getting ready to bloom. The flower is so-so; it’s a milky blue-white flower. What I really grow it for is, after it flowers, it continues to emerge. It will get up to waist-high on me and has this feather-boa foliage. You want to touch it. You want to fondle it! It’s just this glorious feathery wispy foliage that moves around in the wind, and then in the fall turns golden yellow. And then all of the foliage falls off after about three weeks of the golden color. Then you have the stems, you break those off, and that’s your maintenance for the year.”

Tree peony in the Mary Livingston Ripley Garden (Photo by Betty Belanus)

Tree peonies are blooming white and yellow at center stage. Draper describes the gigantic flowers as “Dolly Parton Double-D’s” as she points out the subtly placed supports holding the plant upright. She motions to an almost hidden Jack in the Pulpit given to her by a fellow horticulturalist, pulls a handful of foliage, and passes it around for tour-goers to note the garlicky smell. She admonishes a gentleman about to climb into a flower bed with a sharp, “Hey, honey, all parts out!” It is clear that she knows this garden like the back of her hand and takes great pride in it.

A self-described “Indiana farm girl,” Draper earned a degree in horticulture from the state’s land grant university, Purdue. “Purdue gave me a really good foundation, but it wasn’t based in reality,” she said. “As soon as I was working hands-on, on the job, that’s when my true education began.” Her professor and mentor, Dr. Harrison Flint, helped her secure the first of several internships; “like a passalong plant,” she thrived in the gardens she worked in, from Delaware to Illinois, New York to Germany, absorbing knowledge along the way.

The fountain (not yet in operation for the season in this photo) is the centerpiece of the Ripley Garden. (Photo by Betty Belanus)

A secluded bench invites contemplation. (Photo by Betty Belanus)

The garden is designed to attract birds and pollinators. (Photo by Betty Belanus)

A winding path invites visitors to linger. (Photo by Betty Belanus)

A seasonal container garden brightens a corner of the Ripley Garden. (Photo by Betty Belanus)

The Smithsonian is fortunate to benefit from all this experience, but to hear Draper’s side of the story, she’s the fortunate one. She calls the Ripley Garden her “playground.” Wearing her Carhart jeans and Smithsonian Gardens polo shirt, or some variation of this uniform, she spends her day planting flora, maintaining the gardens, and chatting with visitors. Her go-to tools are her cell phone (which she uses to check everything from her emails to the bloom color of a certain flower), her Swiss-made Felco #2 clippers, and her Japanese hori hori digging knife. She describes her condition at the end of the day as “filthy, dirty, and tired…and my hands look ridiculous and nasty.” But she wouldn’t have it any other way. “My poor husband has an office job, and he comes home and he’s just sad.”

At home in Arlington, Virginia, her hobby is—you guessed it—gardening. When she gets home, she “does the stroll” to see how her plants are doing, and often gets so absorbed that she forgets about dinner preparations. She speaks fondly of her fellow “hort-nerds” and says that when they get together they typically talk about plants and complain about the weather. She calls them “kind, hard-working, salt-of-the-earth, the best people on the planet.”

Draper waxes philosophical about what will become of the Ripley Garden when, someday, she turns it over to a new lead horticulturalist. “A garden dies with the gardener,” she mused. “I’m unique, my personality is mine, so the next person here might have different ideas and different visions, and that’s really cool. So, the garden will change. I know it will change. It needs to change.”

Until then, Draper can be found, rain or shine, happily keeping her charges healthy and looking good.

“I’m literally paid to play in the dirt and talk to people from around the world,” she concludes. “Does it get any better than that?”

Janet Draper loves “playing in the dirt” as supervisory horticulturist for the Mary Livingston Ripley Garden. (Photo by Betty Belanus)

Betty Belanus likes to play in the dirt of her backyard garden and aspires to take the Master Gardener course someday. She has been an education specialist and curator at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage since 1987. Interns Emily Brooks and Marie-Louise Orsini helped with this piece, which was originally published by the CFCH magazine, Folklife.

Posted: 25 June 2018

- Categories: