Digging deeper to find Freer’s final resting place

Rosalie Litt became so fascinated by the life of art collector Charles Lang Freer while transcribing his letters, she decided to use her skills to unearth the solution to a minor mystery about where he is buried.

It’s easy to feel connected to the past when you transcribe correspondence as a Smithsonian digital volunteer. That’s what led my husband and me to visit Wiltwyck Cemetery outside Kingston, N.Y. on a sunny afternoon in October 2017, during a trip to the Hudson Valley.

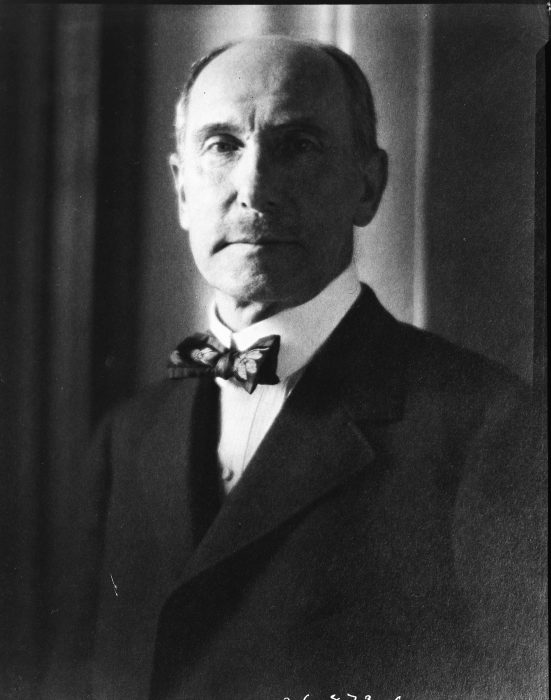

Charles Lang Freer, 1916. (Courtesy Smithsonian Institution Archives)

We wanted to pay our respects to the industrialist and art collector Charles Lang Freer, whose writings I started transcribing for the Smithsonian earlier that year. Freer (1854-1919) was the founding donor and namesake of the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which opened in 1923, and which houses one of the nation’s most important collections of Asian art, along with James McNeill Whistler’s famous Peacock Room.

Freer’s letters include vivid descriptions of his travels in China, Japan and Egypt, his scrapes with overseas customs officials, and his urgent requests to his friend and business manager, Civil War veteran Colonel Frank J. Hecker, for transfers of money to pay for his acquisitions.

Freer’s letters are both lively (“wondrous day”) and businesslike (“Price of jade sword too high. I cannot offer more than six thousand dollars gold…”).

Born in Kingston in February 1854, Freer rose from poverty to wealth. His invalid father was a failed jockey, stable owner and innkeeper. His mother died when he was 14, causing him to leave school to work at a cement factory and a general store.

Freer later found work as a clerk at the New York, Kingston & Syracuse Railroad, where Hecker, then the firm’s superintendent, noticed Freer’s accounting abilities. Hecker and Freer joined forces and moved to Detroit where they became fabulously wealthy manufacturing railroad cars.

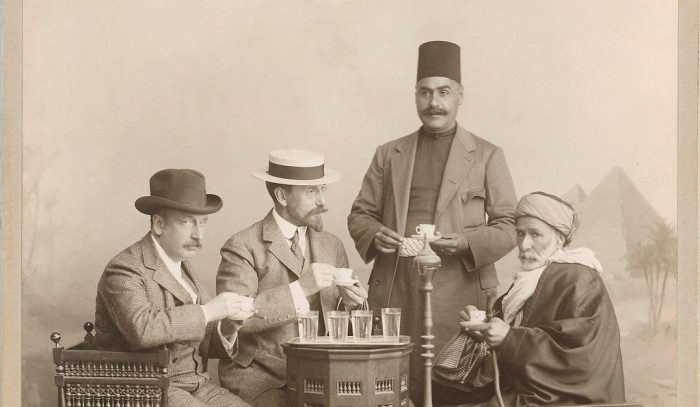

Charles Lang Freer (second from left) and colleagues at a photography studio in Cairo Egypt, 1909 (Courtesy Freer Gallery of Art)

Freer retired in the 1890s due to stress and ill health, and began traveling and collecting art. Contemporaries considered him “staid,” “reticent” and extremely private, particularly about his sexuality [Freer Sackler blog, 2013].

A 1970 memoir published by Agnes Meyer, mother of Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham, outed Freer as gay, according to a 2013 post on the Freer Sackler blog. The author of the article cautioned that Meyer’s tales were questionable, having been “told through the filter of memory.’’

A full biography has yet to be written that would illuminate Freer’s life, showing how he became a great collector, and how he navigated the mores of his time. Curiosity about him led me to want to know more, even if it simply meant finding his grave.

We thought that it should have been easy to locate that final resting place of one of Kingston’s most illustrious natives. That wasn’t so. The website findagrave.com provided the section and lot number of the Freer family plot, but we couldn’t find it by searching on foot or by car among the vast thicket of Gothic spires and Greek and Roman temples in the cemetery’s oldest sections.

Charles Lang Freer (Feb. 25, 1854 – Sept. 25, 1919), Wiltwyck Cemetary, New York county, New York. (Photo by Scott Davies)

After two hours, we steered for the exit, but not before making one final pass. That’s when we spotted the angel. A winged angel atop a gravestone near the railroad tracks at the western edge of the cemetery resembled a similar carving visible in the distance far behind the Freer marker in the photograph on findagrave.com we had been studying by enlarging it on our cell phones.

We reasoned that if we couldn’t find Freer’s tombstone itself, we could triangulate its location by identifying adjacent gravesites. Sure enough, after a few minutes of matching lines of sight with the angel and adjacent trees and tombs, we found ourselves standing in front of the collector’s headstone.

The main slab in the family plot stands about five feet high with the Freer name inscribed above two florettes. Freer’s own stone, set behind the main marker and to the right, is about half as high, with a slightly curved top.

Stains and deterioration have nearly obscured Freer’s name and his birth and death dates. The contrast between the modest gravestone and the museum and collection Freer donated to the United States is striking.

Finding the grave gave us the satisfaction of solving a minor mystery. It also made me appreciate how much more there is to know about Freer and the fascinating life he led. I hope my work as a digital volunteer adds to that understanding.

Rosalie Morss Litt retired from healthcare to raise her children and is now a dedicated volunteer for the Smithsonian Transcription Center. She’s especially interested in first-person, handwritten correspondence or diaries that shed light on personality and character and also the historical context out of which the writings arose.

Posted: 28 August 2018

- Categories: