The making of Labor Day

Find out why we celebrate the American worker by taking the day off.

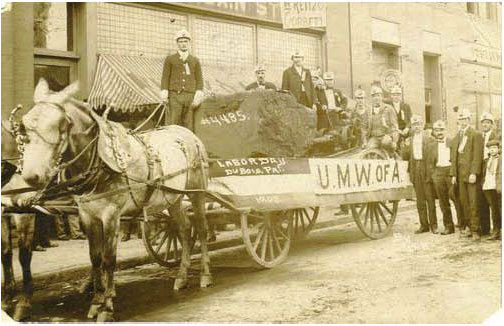

The Women’s Auxilliary Typographical Union float in a Labor Day parade in New York, Sept. 6, 1909. (Via Library of Congress)

Labor Day, in its origins a 19th century celebration of the dignity of work, swiftly evolved into today’s pleasant pause at the end of summer before the coming of new, chillier seasons and life indoors. Arguably a response (in the United States, Canada, and an assortment of other countries) to the widespread socialistic celebration of Mayday, which coincides with the age-old rituals of spring, Labor Day sets off the New World, or at least North America, from the traditions of the Old.

Conflicting accounts trace the first American Labor Day to the inspiration of a local New Haven, Connecticut machinist, Matthew Maguire, or to that of the influential leader of the Carpenters’ union, Peter McGuire. In both accounts, 1882 became the key moment when the American Federation of Labor, a movement of craft unions and local central labor federations, solidified their young and fragile institutions. Largely German and Irish in most places, these unions and federations had traditions of summer holidays, and the institutional support to make the day’s events successful combinations of speech-making, beer drinking, and family fun.

John L. Lewis, one of America’s foremost labor leaders, wore this badge at the 1936 United Mine Workers of America convention. (Via National Museum of American History)

In the era of bitter and often violent conflict between labor and capital, Republican and Democratic parties competed, especially at the local level, for workingmen’s votes. These votes had been especially crucial for Democrats, who claimed the loyalty of the lower classes since at least the presidency of Andrew Jackson. This loyalty was later reaffirmed by the connections of craft unions with local political decisions on urban construction projects of all kinds. However, waves of strikes from the early 1880s to the middle 1890s found Democratic officials, at the behest of manufacturers and merchants, calling out the police against strikers, thus threatening political loyalties. The Pullman Strike of 1894, where the army was used for the first time against striking workers (including the highly organized railroad engineers), seemed to push the problem to the breaking point.

The Pullman Strike, led by future Socialist presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs, was crushed, and Debs himself imprisoned. Within days of the strike’s end, Democratic President Grover Cleveland rushed a bill recognizing Labor Day through Congress. Not a single elected official in Congress voted against this measure—a fitting symbol for the claim, accurate or not, that American society was unique for its social compact between rich, poor, and middle classes.

President Cleveland himself chose the September date in order to set the American holiday off from European Mayday. An AFL resolution of 1909 declared the first Sunday to be the proper Labor Day, perhaps because Sunday holidays had long been popular for workers enjoying beer in picnic areas outside cities where Sunday sales were banned. Eventually, all states and the District of Columbia affirmed the holiday status for their residents. Although Labor Day was originally celebrated on Sunday, in 1968 Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act. The act moved several federal holidays, including Labor Day, to Mondays.

This post by historian Paul Buhle was originally published on the American History Museum’s blog, “O Say Can You See?” Buhle is a retired Senior Lecturer at Brown University and a longtime labor historian. He lives in Madison, Wisconsin, and edits non-fiction, historical comic art books.

Posted: 1 September 2018

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture