Drawing on a half-century’s experience

A self-taught illustrator, Vichai Milikul has been creating meticulous scientific drawings of the minutiae of mosquitoes and other insects for more than 50 years.

LBJ was in the White House, the opening of the National Air and Space Museum was nine years away, and Elvis Presley was still the King when Vichai Malikul moved from Thailand to Washington, D.C. in 1967 to take a job as a scientific illustrator for the U.S. Army’s South East Asia Mosquito Project.

A year earlier, Malikul had contributed his first major professional illustrations to “The Key to The Female Anopheles Mosquitoes of Thailand,” a U.S. Army publication authored by his supervisor, Col. John E. Scanlon.

When Scanlon was reassigned to the U.S. after his stint in Thailand, he established a mosquito research laboratory at the Smithsonian and immediately asked Malikul to join him to continue their work studying malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Soon after, entomologist Yiau-Min Huang, an expert in dengue fever mosquitoes, joined them. Huang is still working at the Smithsonian’s Department of Entomology, stationed in a laboratory in Suitland, Md.

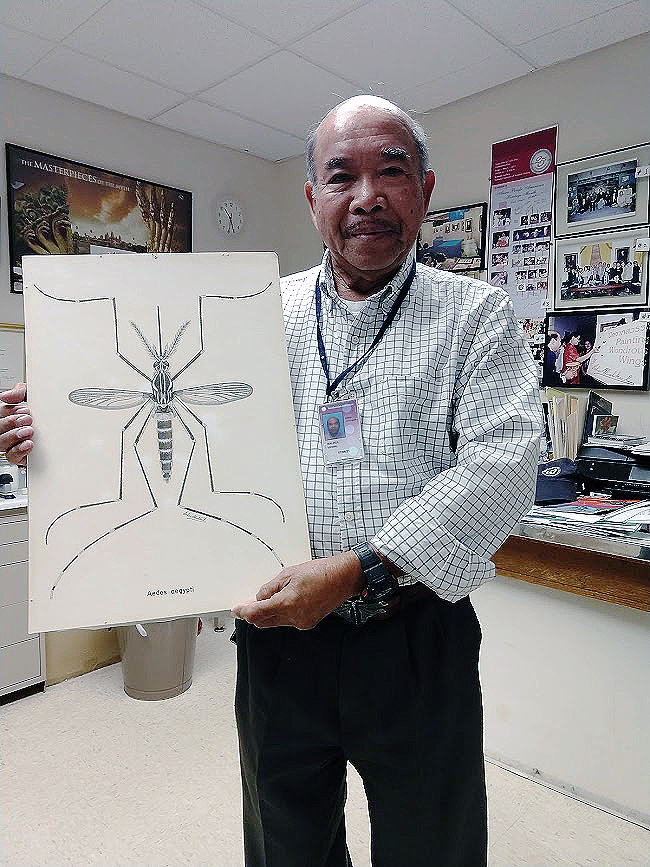

In his office Vichai Malikul holds a very early illustration he did of the yellow fever mosquito: “Aedes aegytpi.” It can also spread dengue fever, chikungunya and Zika. (John Barrat photo)

Malikul’s first office was in a small rented building at 7th and Lamont Streets, N.W., called the Laundry Building. “I never knew if it had a laundry in it or not,” he laughs, “but it is still there.” After a number of buildings in the neighborhood were burned during riots sparked by the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Malikul and his colleagues were moved to the Natural History Museum.

From 1967 to 1982 Malikul worked for the U.S. Army, creating illustrations to accompany scientific publications describing new mosquito species, specifically those that carry malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever and other human pathogens.

In fact, Dr. Huang named one new species of mosquito Aedes (Stegomyia) malikuli to honor of the illustrations he contributed to the research they published in many volumes of Contributions of the American Entomological Institute.

Since 1984 he has been working with Smithsonian entomologists Don Davis, Robert Robbins, and others, drawing illustrations for scientific journals.

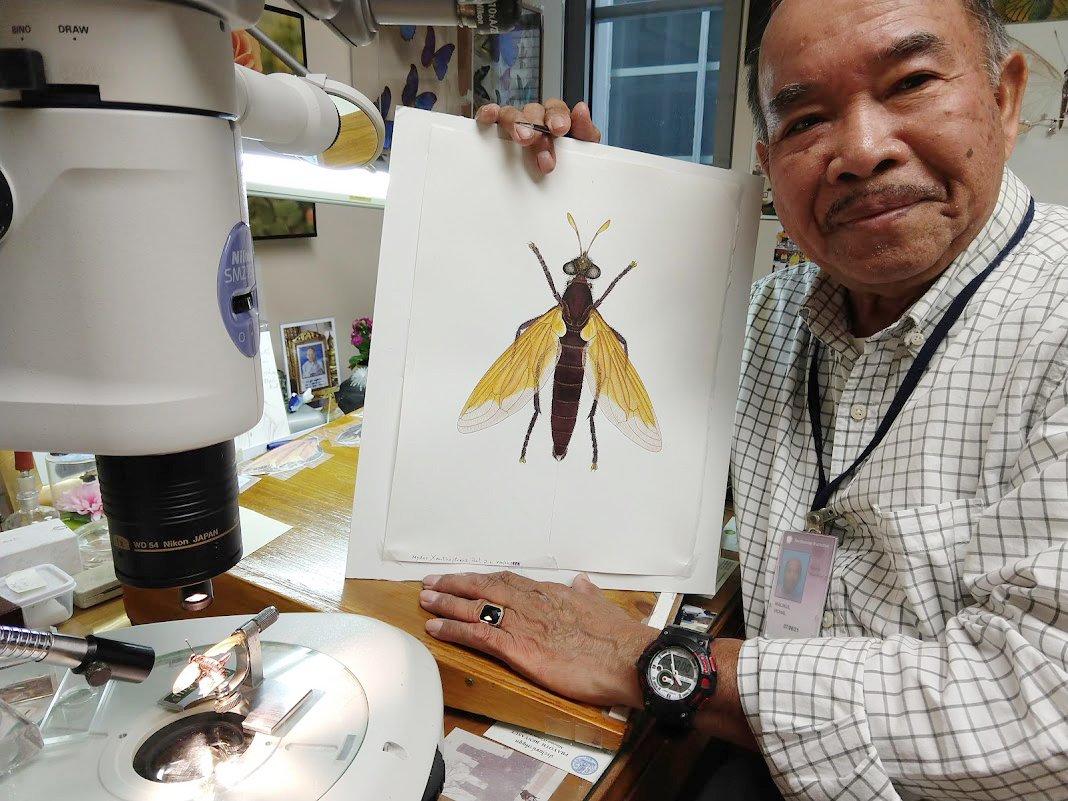

Describing a new insect species is an exacting science requiring close examination and comparison of the new species with known and previously described species. After taking precise measurements and describing a new insect in scientific terms, an entomologist turns the specimen and its written description over to Malikul. Reading the description carefully, Malikul begins to create a drawing of the specimen using ink and acrylic paint and very fine sable brushes.

All work is done gazing into a microscope, enlarging the insect’s features so they are exact and easily viewable to the naked eye. “A specimen or parts of a specimen are usually broken, so it is my duty to make it perfect again in an illustration,” Malikul says. “Also, a specimen I am given may be the only specimen in the world and the only known example of a new species, so I must be careful not to damage it.”

Peering through the eyepiece of a stereo microscope Vichai observes the characteristics of a fly he is drawing meticulously transfers them to paper with his right hand. (Photo by John Barrat)

Vichai Malikul holds a completed drawing. (Photo by John Barrat)

For most publications Malikul creates drawings for each stage of an insect’s life—larva, pupae and adult—using specimens from each stage provided by the scientist. Once complete, Malikul’s drawings are reviewed by the entomologist describing the insect. Each illustration is a remarkable achievement of detail. Malikul estimates he has completed detailed illustrations of some 800 different insect species.

In a field that is increasingly becoming dominated by high-resolution digital photography, scientific illustration still has a place.

Malikul’s mosquito illustrations, for example, are still used by medical staff and others across the world to identify mosquito species in the field that over the centuries have killed millions of humans.

In 2016, two black-and-white illustrations by Malikul of mosquitoes that carry the Zika virus—Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus—were printed on the front page of the New York Times.

“My mosquito illustrations are still worthwhile,” Malikul says. “I am very proud of how they have been used to help detect disease carrying mosquitoes and how my other illustrations, such as those of micro moths called leaf minors, have been used to benefit agriculture.”

A self-taught illustrator, Malikul has returned regularly to Thailand on vacation to give week-long workshops in scientific illustration at various universities and science museums in Bangkok and other providences in Thailand.

“Illustrating is a good type of work if you like it,” he says. “If you don’t, I don’t think you will last long. Even now there are many other entomologists, such as Smithsonian butterfly expert Robert Robbins and fly expert Torsten Dikow, who have specimens for me to illustrate.”

In a February 2015 paper in the journal Insect Systematics and Evolution entomologists Robert K. Robbins of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and Robert C. Busby, named this new Panamanian butterfly Lathecla vichai, after Vichai Malikul. In their paper they stated: “It gives us great pleasure to name this species in appreciation of Vichai Malikul. With a trained eye and enormous native talent, Vichai has illustrated genitalia and other eumaeine structures for decades. The name is a noun in apposition.” Illustration by Vichai Malikul.

Link to paper: (https://entomology.si.edu/StaffPages/Robbins/2015_lathecla2ndarySexStructures.pdf)

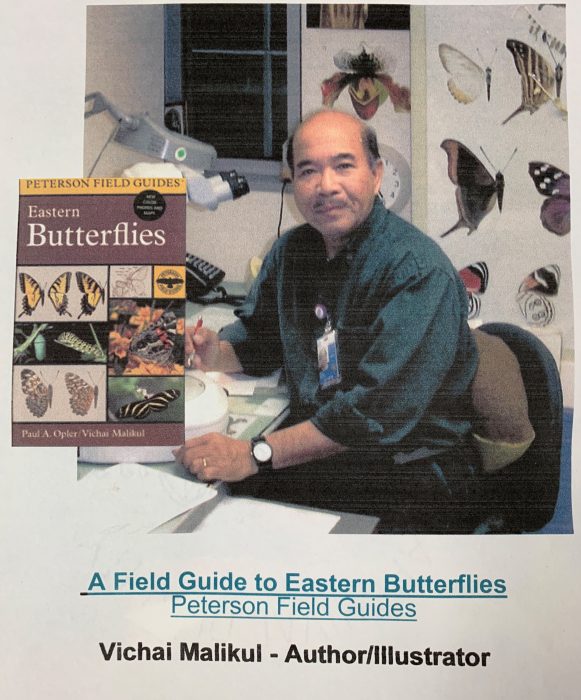

In 1982, Malikul started a side project illustrating the “Peterson Field Guide to Eastern Butterflies.” It took him more than six years to complete, working on his own time at home to create the guide’s 541 color paintings of butterfly wings. The guide is still widely used for identifying butterfly species and as a field guide by nature lovers.

Malikul illustrated more than 300 butterfly species for this book.

Looking over illustrations that he did more than 30 to 40 years ago, Malikul marvels today at how he made them so small, yet detailed.

“That was back then my eyesight was good,” he laughs. “It’s fun–when you like what you are doing it is timeless. I was lucky all my life, good connections, working with good friends at the Smithsonian.

“I learned to draw these illustrations by myself. There was no school teaching this in Thailand back in the 1960s,” he adds. “I learned by studying the mosquito illustrations of a Japanese scientific illustrator from a publication. Now that I know just how difficult it is, I sometimes find it incredible. I don’t know how I did it.”

In February 2010 Vichai Malikul visited the North Chevy Chase Elementary School in Kensington, Maryland to present a scientific illustration workshop on butterfly illustrations. The activity involved four sessions for 5th graders, with some 150 students involved. (Photo courtesy Vichai Malikul)

Today, Malikul can still be found a few days each week calmly gazing into a stereo-microscope in his office in the Entomology Department at the Natural History Museum, despite having officially retired in June 2018 after 51 years on the job.

He carefully adjusts the pinned specimen of a tiny moth on the microscope’s viewing stage with his left hand, while drawing the insect’s miniscule features with his right hand. Adorning nearly every vertical and horizontal surface in his office are dozens and dozens of illustrations, photographs and awards that document his long career observing and drawing perfectly detailed illustrations of the world’s tiniest creatures. He is particularly proud of the 2007 Unsung Hero Award he received—a recognition of the important work done behind-the scenes that many, many staff perform to enable the Smithsonian’s mission.

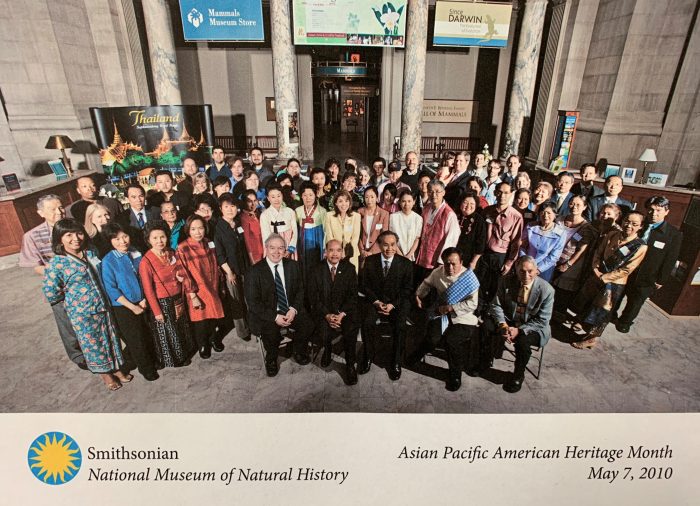

Vichai organized Asian Pacific American Heritage Month celebrations for many years.

Among Malikul’s many contributions and achievements, he has directed Asian and Pacific American Heritage Month activities and programs at the Smithsonian, raised thousands of dollars to assist victims of the 2004 tsunami in Thailand, served as commissioner to the state of Maryland for Asian and Pacific American affairs and has led numerous scientific illustration workshops in the United States, Canada and Thailand.

Vichai Malikul with the award he received in 1996 from the Human Relations Society of Bangkok for his many years of promoting Thai culture in the United States

In 2010, Malikul was awarded the Order of Direkgunabhorn Silver Medal Decoration from His Majesty the King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand in honor of his lifetime of service to the Thai and Asian American community.

From left Vichai and Nit Malikul, Ambassador to the United States Don Pramudwinai, and the Malikul daughters at the Thai Embassy in 2010. (Image courtesy Vichai Malikul)

When Malikul moved to Washington, has asked his fiancée to join him. Vichai Malikul and Phuangthong Fuangarom “Nit” were married by the ambassador of Thailand at his D.C. residence in 1968. This year marks their 50th anniversary. Nit retired three years ago after 34 years working as lab technician at the USDA Systematic Entomology Laboratory in Beltsville, Md.

Nit and Vichai live in Silver Spring, have two grown daughters, and are active in the Thai Temple for Thai American and the Asian American communities of Maryland, Virginia and Washington, D.C. He also plans to spend time teaching scientific illustration workshops with the intention of passing on his knowledge, experience and passion to others.

In the clip below, Malikul and his wife share their expertise in the traditional Thai art of fruit and vegetable carving as part of a program at the 2009 Asian Pacific American Heritage Month celebration.

Posted: 29 November 2018