Knowing the Past Opens the Door to the Future

Lonnie Bunch III, the founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, offers a thoughtful look at the continuing importance of Black History Month.

No one has played a greater role in helping all Americans know the black past than Carter G. Woodson, the individual who created Negro History Week in Washington, D.C., in February 1926. Woodson was the second black American to receive a PhD in history from Harvard—following W.E.B. Du Bois by a few years. To Woodson, the black experience was too important simply to be left to a small group of academics. Woodson believed that his role was to use black history and culture as a weapon in the struggle for racial uplift. By 1916, Woodson had moved to DC and established the “Association for the Study of Negro Life and Culture,” an organization whose goal was to make black history accessible to a wider audience. Woodson was a strange and driven man whose only passion was history, and he expected everyone to share his passion.

Carter G. Woodson. (Scurlock Studio Records, ca. 1905-1994, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

This impatience led Woodson to create Negro History Week in 1926, to ensure that school children be exposed to black history. Woodson chose the second week of February in order to celebrate the birthday of Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. It is important to realize that Negro History Week was not born in a vacuum. The 1920s saw the rise in interest in African American culture that was represented by the Harlem Renaissance where writers like Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglass Johnson, Claude McKay—wrote about the joys and sorrows of blackness, and musicians like Louie Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Jimmy Lunceford captured the new rhythms of the cities created in part by the thousands of southern blacks who migrated to urban centers like Chicago. And artists like Aaron Douglass, Richard Barthe, and Lois Jones created images that celebrated blackness and provided more positive images of the African American experience.

Woodson hoped to build upon this creativity and further stimulate interest through Negro History Week. Woodson had two goals. One was to use history to prove to white America that blacks had played important roles in the creation of America and thereby deserve to be treated equally as citizens. In essence, Woodson—by celebrating heroic black figures—be they inventors, entertainers, or soldiers—hoped to prove our worth, and by proving our worth—he believed that equality would soon follow. His other goal was to increase the visibility of black life and history, at a time when few newspapers, books, and universities took notice of the black community, except to dwell upon the negative. Ultimately Woodson believed Negro History Week—which became Black History Month in 1976—would be a vehicle for racial transformation forever.

The question that faces us today is whether or not Black History Month is still relevant? Is it still a vehicle for change? Or has it simply become one more school assignment that has limited meaning for children. Has Black History Month become a time when television and the media stack their black material? Or is it a useful concept whose goals have been achieved? After all, few—except the most ardent rednecks – could deny the presence and importance of African Americans to American society or as my then-14 year old daughter Sarah put it, “I see Colin Powell everyday on TV, all my friends—black and white—are immersed in black culture through music and television. And America has changed dramatically since 1926—Is not it time to retire Black History Month as we have eliminated white and colored signs on drinking fountains?” I will spare you the three hour lesson I gave her.

I would like to suggest that despite the profound change in race relations that has occurred in our lives, Carter G. Woodson’s vision for black history as a means of transformation and change is still quite relevant and quite useful. African American history month, with a bit of tweaking, is still a beacon of change and hope that is still surely needed in this world. The chains of slavery are gone—but we are all not yet free. The great diversity within the black community needs the glue of the African American past to remind us of not just how far we have traveled but lo, how far there is to go.

While there are many reasons and examples that I could point towards, let me raise five concerns or challenges that African Americans — in fact — all Americans — face that black history can help address:

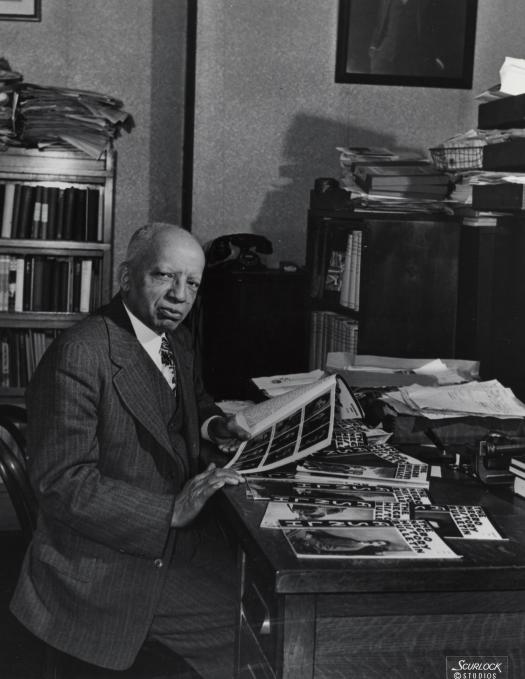

Dr. Carter G. Woodson, late 1940s (Scurlock Studio Records, ca. 1905-1994, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

The Challenge of Forgetting

You can tell a great deal about a country and a people by what they deem important enough to remember, to create moments for — what they put in their museum and what they celebrate. In Scandinavia — there are monuments to the Vikings as a symbol of freedom and the spirit of exploration. In Germany during the 1930s and 1940s, the Nazis celebrated their supposed Aryan supremacy through monument and song. While America traditionally revels in either Civil War battles or founding fathers. Yet I would suggest that we learn even more about a country by what it chooses to forget — its mistakes, its disappointments, and its embarrassments. In some ways, African American History month is a clarion call to remember. Yet it is a call that is often unheeded.

Let’s take the example of one of the great unmentionable in American history — slavery. For nearly 250 years slavery not only existed but it was one of the dominant forces in American life. Political clout and economic fortune depended on the labor of slaves. And the presence of this peculiar institution generated an array of books, publications, and stories that demonstrate how deeply it touched America. And while we can discuss basic information such as the fact that in 1860 — 4 million blacks were enslaved, and that a prime field hand cost $1,000, while a female, with her childbearing capability, brought $1,500, we find few moments to discuss the impact, legacy, and contemporary meaning of slavery.

In 1988, the Smithsonian Institution, about to open an exhibition that included slavery, decided to survey 10,000 Americans. The results were fascinating — 92% of white respondents felt slavery had little meaning to them — these respondents often said “my family did not arrive until after the end of slavery.” Even more disturbing was the fact that 79% of African Americans expressed no interest or some embarrassment about slavery. It is my hope that with greater focus and collaboration Black History Month can stimulate discussion about a subject that both divides and embarrasses.

As a historian, I have always felt that slavery is an African American success story because we found ways to survive, to preserve our culture and our families. Slavery is also ripe with heroes, such as slaves who ran away or rebelled, like Harriet Tubman or Denmark Vessey, but equally important are the forgotten slave fathers and mothers who raised families and kept a people alive. I am not embarrassed by my slave ancestors; I am in awe of their strength and their humanity. I would love to see the African American community rethink its connection to our slave past. I also think of something told to me by a Mr. Johnson, who was a former sharecropper I interviewed in Georgetown, SC:

Though the slaves were bought, they were also brave. Though they were sold, they were also strong.

Dwayne Wilson of Delaware, who was on his first visit to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, sits in the Contemplative Court. The room, which features an indoor water cascade, has become a favorite spot in the museum for many. (Evelyn Hockstein for The Washington Post)

The Challenge of Preserving a People’s Culture

While the African American community is no longer invisible, I am unsure that as a community we are taking the appropriate steps to ensure the preservation of African American cultural patrimony in appropriate institutions. Whether we like it or not, museums, archives, and libraries not only preserves culture they legitimize it. Therefore, it is incumbent of African Americans to work with cultural institutions to preserve their family photography, documents, and objects. While African Americans have few traditions of giving material to museums, it is crucial that more of the black past make it into American cultural repositories.

A good example is the Smithsonian, when the National Museum of American History wanted to mount an exhibition on slavery, it found it did not have any objects that described slavery. That is partially a response to a lack of giving by the African American Community. This lack of involvement also affects the preservation of black historic sites. Though there has been more attention paid to these sites, too much of our history has been paved over, gone through urban renewal, gentrified, or unidentified, or un-acknowledged. Hopefully a renewed Black History Month can focus attention on the importance of preserving African American culture.

There is no more powerful force than a people steeped in their history. And there is no higher cause than honoring our struggle and ancestors by remembering.

The Challenge of Maintaining a Community

As the African American Community diversifies and splinters, it is crucial to find mechanisms and opportunities to maintain our sense of community. As some families lose the connection with their southern roots, it is imperative that we understand our common heritage and history. The communal nature of black life has provided substance, guidance, and comfort for generations. And though our communities are quite diverse, it is our common heritage that continues to hold us together.

The Power of Inspiration

One thing has not changed. That is the need to draw inspiration and guidance from the past. And through that inspiration, people will find tools and paths that will help them live their lives. Who could not help but be inspired by Martin Luther King’s oratory, commitment to racial justice, and his ultimate sacrifice. Or by the arguments of William and Ellen Craft or Henry “Box” Brown who used great guile to escape from slavery. Who could not draw substance from the creativity of Madame CJ Walker or the audacity and courage of prize fighter Jack Johnson. Or who could not continue to struggle after listening to the mother of Emmitt Till share her story of sadness and perseverance. I know that when life is tough, I take solace in the poetry of Paul Lawrence Dunbar, Langston Hughes, Nikki Giovanni, or Gwendolyn Brooks. And I find comfort in the rhythms of Louie Armstrong, Sam Cooke or Dinah Washington. And I draw inspiration from the anonymous slave who persevered so that the culture could continue.

Let me conclude by re-emphasizing that Black History Month continues to serve us well. In part because Woodson’s creation is as much about today as it is about the past. Experiencing Black History Month every year reminds us that history is not dead or distant from our lives.

Rather, I see the African American past in the way my daughter’s laugh reminds me of my grandmother. I experience the African American past when I think of my grandfather choosing to leave the South rather than continue to experience share cropping and segregation. Or when I remember sitting in the back yard listening to old men tell stories. Ultimately, African American History — and its celebration throughout February — is just as vibrant today as it was when Woodson created it 85 years ago. Because it helps us to remember there is no more powerful force than a people steeped in their history. And there is no higher cause than honoring our struggle and ancestors by remembering.

Lonnie Bunch, founding director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. (Jahi Chikwendiu / The Washington Post)

This post was originally published by the National Museum of African American History and Culture blog, Our American Story.

Posted: 1 February 2019