The Mammal Fossil in Dinosaur Hall and What We Did Not Know

The Smithsonian’s Brian Huber, who at the time headed the paleobiology department, wanted my visit to begin in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History dinosaur hall, where the sloth was on view, so that I could first see a giant sloth as a completed whole. (The exhibition closed in 2014 for renovations and will reopen June 8 under the name “The David H. Koch National Fossil Hall—Deep Time.”)

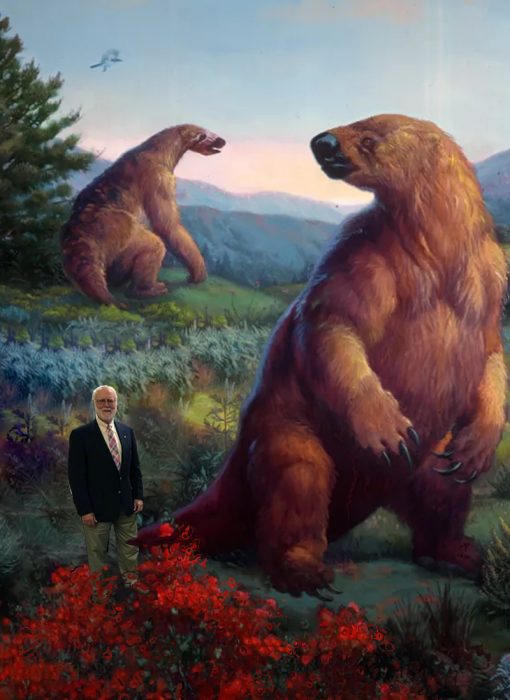

Smithsonian paleobiologist Brian Huber (Photo by Donny Bajohr)

Then he took me into the museum’s paleontological collections to see some of the “spare parts.” The giant sloth skeleton on display was actually only partly authentic, since it was constructed using skeletal remains that were incomplete. Plaster parts made to look like the real thing completed the skeleton, and it is here that south Georgia enters the equation.

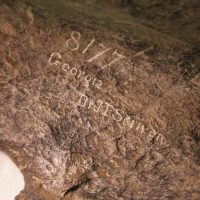

Screven’s paper provided the documentation that he was the donor of the fossils; “Seriven” was a misspelling on the specimen tag. (Photo by Donny Bajohr)

Leaving the hall, we made our way through several floors containing hundreds of large collection cabinets; the dim halls are only fully lit when in use. We walked into a central area where paleontologist David Bohaska had arrayed a selection of bones on a metal table. Among the odd joints and leg bones was the lower jawbone of a large creature with molars about 20 times bigger than those of a human. The collection tags were yellowed with age and indicated the remains had been classified as those of a Megatherium and had been obtained from “Skiddaway” Island by Dr. J. P. Seriven. This fossil find was important to science not just because it was an intact jawbone of the creature, but also because it was the first to show that the Megatherium had existed in North America. (Hang on to this thought, because it turns out there is more to this story.)

While we were viewing the fossil bones, I noted that “Skiddaway” was probably Skidaway, an island that is almost a suburb of Savannah, Georgia. I had visited it several times during my tenure as president of Georgia Tech, because it has a marine station that university scientists use as a base for research. I felt sure of my conclusion because the state park on the island has a small museum that features an exact copy of the Natural History Museum’s giant ground sloth.

The fossil was from south Georgia. And it was an important one, since it firmly establish the presence of the genus Megatherium, which had previously been unknown in the United States. However, as would turn out to be the case more than a few times in my search, what seemed to be a done deal was not done at all.

First, there was the word “Skiddaway” on the collection tag. Could it be more than a simple case of misspelling? Then, Huber told me that what was written on the collection tag as the genus of the specimen reflected the state of the art at the time. More recently, changes had been made in the classification of giant ground sloths. As a result, Huber said, the Georgia fossil was most likely an Eremotherium, not a Megatherium as the collector had thought.

Most people who wander into a museum to look at fossils for fun would have a hard time noticing any difference between Eremo and Mega sloths, but to experts significant differences exist. The two were similar in size (i.e., big), but according to the British paleontologist Darren Naish, the former genus [Eremotherium] is “characterized by a shallower maxilla with reduced hypsodonty of the upper teeth compared to the latter species [Mega].”

- When I came up with the notion for my new book connecting my south Georgia home to the Smithsonian collections, I had no idea it would lead me to giant ground sloths. (Photo by Donny Bajohr)

- We walked into a central area where paleontologist David Bohaska had arrayed a selection of bones on a metal table. (Photo by Donny Bajohr)

- Among the odd joints and leg bones was the lower jawbone of a large creature with molars about 20 times larger than those of a human. (NMNH)

- This fossil find was important to science because it was an intact jawbone of the creature. (Photo by Donny Bajohr)

- The collection tags were yellowed with age and indicated the remains had been classified as those of Megatherium and had been obtained from “Skiddaway” Island. (Photo by Donny Bajohr)

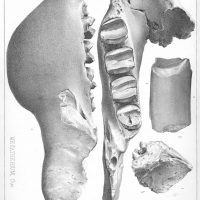

- Joseph leidy named the fossil Magatherium mirabile and published this illustration in the 1855 Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge series. (NMNH)

I had no idea what “reduced hypsodonty” is, but I learned that the Eremotherium was the North American descendant of the South American Megatherium. The two began to separate into different species some three million years ago when a group of adventurous Megas moved north across the newly formed land bridge between North and South America, which later became known as the Isthmus of Panama.

This movement of species from South America to North America and vice versa is known among paleontologists as the Great American Biotic Interchange, but it was an unequal exchange. The creatures that headed south from North America were typically more successful than those going north, so what would become our giant sloth, the Eremotherium, was an exception. As to the south Georgia collector who misidentified the fossil remains in the 1800s, we can absolve him, because the difference between the two species was not understood until 1948.

When I reviewed the documentation in the fossil records with the help of the Smithsonian Archives, I found that the jawbone originally had been donated in 1842 to an organization called the National Institute for the Promotion of Science in Washington, D.C. The Smithsonian Institution did not open its doors until 1846, but it soon eclipsed the National Institute, which folded in the 1850s and gave its collections, including the fossil from “Skiddaway” Island, to the Smithsonian.

To find out about the collector, I did an online search for J. P. Seriven and found a number of people with that name, but none seemed to fit the bill. Related names did keep popping up, however, namely Dr. J. P. Screven or Scriven. Regardless of the spelling, these references pointed to a man who had lived in Savannah about the same time as the fossil discovery.

I located a 1913 source in the Chatham County Archives by William Harden about Screven. According to Harden, Dr. James Proctor Screven, who was born in 1799 in Bluffton, South Carolina, came from a family with deep roots in the area. He had relatives who fought in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 and the Indian Wars of Andrew Jackson. Family members operated rice plantations in the area, but Screven was cut from a different cloth than most of his contemporaries, and he chose to attend medical school at the University of Pennsylvania.

After receiving his degree in 1820, Screven was supported by his father for two years while he lived first in England and then in France to observe the medical practices in different countries. While in Europe, he spent time studying geology and natural science as a matter of personal interest. It was an enlightened era when scientists were in high pursuit of discoveries. New developments were frequently announced, leading to improved understanding of mountain building, the effects of glaciation, and the evolution of species. After he returned to the United States, Screven set up a medical practice in 1822 in Savannah, but he kept up his interest in science and history.

An 1846 memoir written by William Hodgson provided the details of Screven’s involvement with fossils. Hodgson reported that Screven was a friend of another medical doctor in Savannah, John C. Habersham, who was an avid fan of fossils and antiquities. According to Hodgson, in 1823 Screven and Habersham were invited by a plantation owner named Stark to examine fossil bones that were exposed at low tide in a soil bank adjacent to a tidal pond on his property. Hodgson stated that the plantation was on “Skiddaway” Island, confirming my hypothesis.

Skidaway Island State Park (photo copyright 2015 Eric Champion for Atlanta Trails)

Screven and Habersham acquired a set of fossil bones from the plantation, and after Screven had studied them, he identified them as a species of Megatherium. He moved quickly, reporting his findings to the Georgia Medical Society in 1823. Poor Habersham may have gotten the short end of the stick in this business, since it would turn out that he was by far the more committed of the two to paleontology. Regardless, Screven’s paper provided the documentation that he was the donor of the fossils to the National Institute; “Seriven” was a misspelling on the specimen tag.

Screven’s interests soon moved away from fossils and toward his medical practice and, in 1835, to full-time work on his inherited South Carolina and Georgia landholdings and rice plantations. But rather than living a life of leisure, he moved to downtown Savannah and set about doing all he could to improve the city. Serving as an alderman and eventually mayor, he is credited with developing a clean water system, a gas supply system and the public schools of Savannah. He died in 1859.

We don’t know much about what Screven did with the fossil bones after he identified them as Megatherium in 1823, but in 1842 he presented drawings of them to a meeting of the National Institute for the Promotion of Science in Washington, D.C. Soon he also donated the fossils to the organization, a gift that I confirmed through the Smithsonian Archives with the help of Smithsonian historian Pam Henson. She also tracked down an article in the National Intelligencer dated September 9, 1842, which contained a letter from Screven to the National Institute for the Promotion to Science:

I have this day shipped three boxes of fossil remains to your address care of William Habersham of Baltimore [perhaps a relative of John C. Habersham]. . . . The bones in the upper part of the box (the largest one) are fragments of the bones of the extinct animal called by comparative anatomists Megatherium. . . . These remains of the Megatherium were found by Dr. J. C. Habersham and myself on Skidaway Island fourteen miles southeast of Savannah.

A corresponding member, Dr. E. Foreman, wrote:

This Institution has received recently a noble donation from Dr. J. P. Screven of Savannah, Georgia, consisting of his entire collection of gigantic remains of the Megatherium which belong to an extinct race of animals, discovered by him on the coast of Georgia many years ago, and for the first time in North America.

While it would be about a hundred years before these fossil bones were identified as Eremotherium, at least one scientist recognized their distinction from Megatherium early on. Joseph Leidy, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and a collaborator with the Smithsonian, named them Megatherium mirabile in the 1855 Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge series.

In his brief biography of Screven, Harden reported that after being moved to the Smithsonian when the Institute for the Promotion to Science closed its doors, the fossils were lost in a fire. Fortunately, at least some of the important parts of the collection were spared, because I saw them myself.

Things New and Strange: A Southerner’s Journey through the Smithsonian Collections

G. Wayne Clough demonstrates in the most exemplary way how any American, or for that matter any citizen of the world, can use the Smithsonian Institution’s increasingly digitized collections for self-discovery and find in them their own deep, personal connections to natural history, world events, and the American experience. Things New and Strange is beautifully written and inspiring to read.

Dr. Clough will discuss his book with Smithsonian Associates Director Frederica Adelman June 20 at 6:45. Tickets and more information are available from Smithsonian Associates.

This article was originally published by Smithsonian.com