Collecting the Collectors

Magnificent Obsessions: Why We Collect explores our human urge to gather stuff

“Magnificent Obsessions” is the latest exhibition from Smithsonian Libraries.

At the core of Magnificent Obsessions, the latest exhibition in the Smithsonian Libraries Gallery at the National Museum of American History (1 West), is the universal yen to collect. The exhibition highlights the fascinating stories of the sometimes eccentric book collectors whose varied interests helped form and contribute to the Smithsonian Libraries.

“Everybody collects something,” says Mary Augusta Thomas, deputy director of the Smithsonian Libraries and co-curator of Magnificent Obsessions. Aside from the pure pleasure of amassing cherished items, collections “give you a sense of people’s private passions and reflect our cultural heritage.”

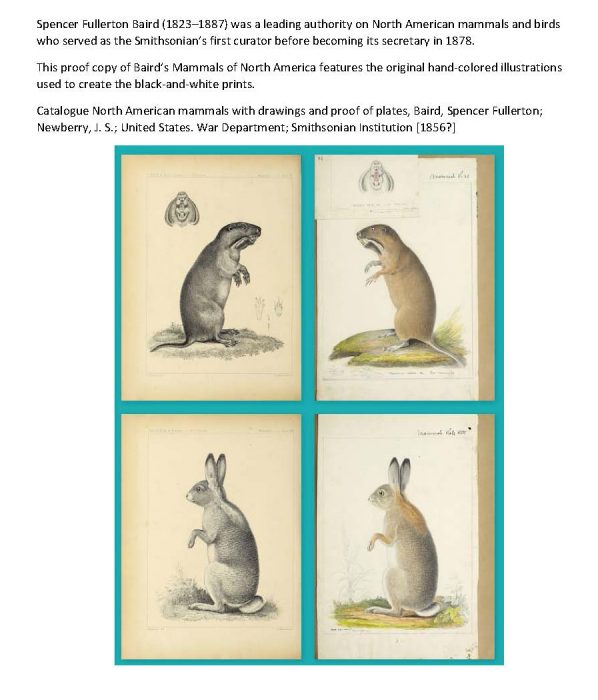

In this exhibition, seemingly disparate themes—a sheaf of vintage Tupperware ads sit near detailed drawings of North American mammals assembled by former Smithsonian Secretary Spencer Baird— underscore the gigantic range of interests that have captured American imaginations since the country’s founding.

The collections celebrated in Magnificent Obsessions were drawn from several of the Libraries’ 21 branches around the Smithsonian, Thomas says. A cache of sheet music with aviation themes from the Air and Space Museum Library appears alongside “Le Jazz,” an issue of Le Point magazine (1952), a jazz publication from Ella Fitzgerald’s personal collection housed at the National Museum of African American History and Culture Library.

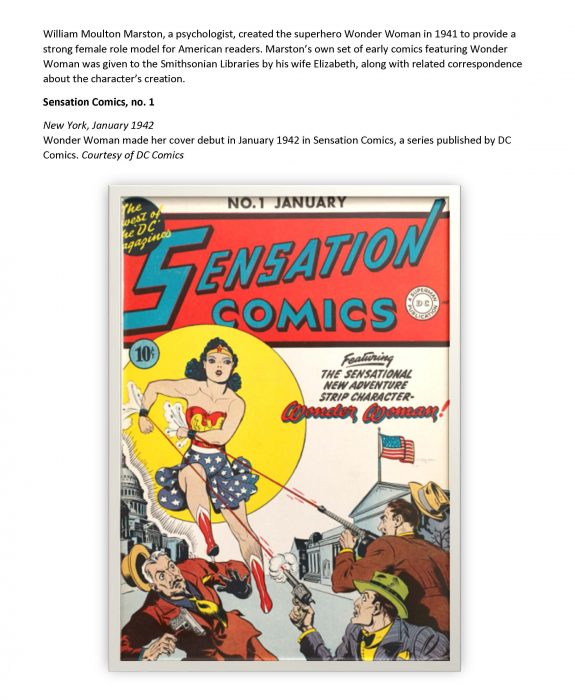

“[Visitors] understand why we have beautifully illustrated books,” Thomas says. “It may be less clear why” the Libraries also possess a trove of Wonder Woman ephemera.

No matter what collectors seek out, the act of gathering itself is telling. “If people did not have a passion for saving these things, they would not have survived,” she observes—and an invaluable window into popular culture would be lost. The power of possession can fire a passion for acquisition limited only by the collector’s imagination. “Someone put these things together in a way that was valuable to them,” Thomas continues.

Items from the Libraries’ renowned World’s Fairs collection are well represented, but a lesser-known collection of books about grasses (gathered by former Smithsonian botanist Mary Agnes Chase) is no less intriguing.

Mary Agnes Chase (1869-1963), sitting at desk with specimens via Smithsonian Institution Archives

Collections humanize their collectors and add new details to our perceptions of them. For example, Chase had no formal education beyond grammar school but nonetheless became one of the “world’s outstanding agrostologists,” according to the National Museum of Natural History’s biography. Our admiration of her scientific accomplishments is only enhanced by learning that she was also an ardent suffragist who was jailed multiple times fighting for the right of women to vote.

Another hallmark collection here is that of Bern Dibner, an immigrant who donated his massive collection of science and technology books to the Smithsonian at the time of the nation’s bicentennial in 1976. Dibner’s considerable gift established the Smithsonian Libraries’ first rare book library. This led to the creation of the Libraries’ flourishing Special Collections Department, now overseeing a vault of over 50,000 rare books and manuscripts.

Magnificent Obsessions, which opened in November, was co-curated with Stephen Van Dyk, librarian and department head of the Smithsonian Libraries’ five art libraries. It will be on display through 2020, rotating four times. Interactive programs based on the theme of collecting will kick off in the gallery this summer, and a related lecture series begins May 31 with Celebrating Women Book Collectors: The Early Years of the Honey & Wax Prize.

-end-

Posted: 13 May 2019

-

Categories:

Art and Design , Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories , History and Culture , Science and Nature