It does not take many words to tell the truth

On June 25, 1868, Native Americans won a great battle. And lost their longest war.

It is said that history is written by the victor, but in the case of the Battle of the Greasy Grass, the story we all learned as children was written by the defeated.

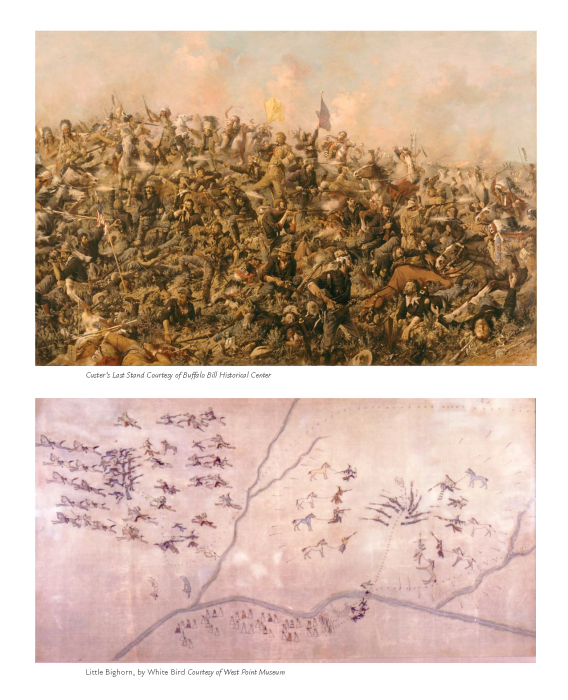

Custer’s Last Stand at the Battle of the Little Big Horn (Greasy Grass) is an iconic moment in the history of the American West—the brave soldiers, led by their gallant, golden-haired general, fighting to the last man against insurmountable odds. That’s the white version, anyway. But like any story shared, it all depends on who’s doing the telling.

The facts are straightforward:

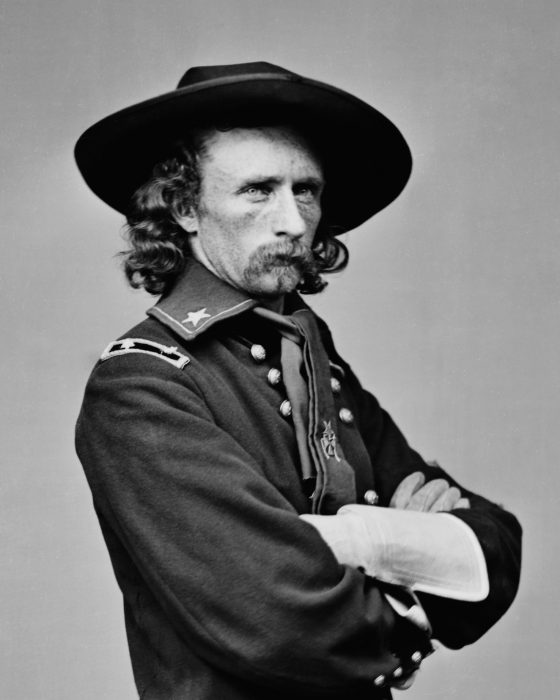

In 1868, the United States made a treaty with the Sioux nation—a loose confederacy that included the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota peoples—that confined them to a reservation in South Dakota and Nebraska. The Treaty of Fort Laramie promised that the Black Hills, which the Sioux considered sacred, would forever be part of their reservation and closed to white settlement. In 1874, however, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer led an expedition that verified rumors of rich gold deposits there in the Black Hills. Prospectors quickly began to trespass on Indian land and stake illegal claims—then demand that the army protect them from Indian attacks. In the summer of 1876, the U.S. Army deployed troops to the Black Hills to trap a group of roaming Sioux and force them back to their reservation. Custer’s Seventh Cavalry and his Crow Indian allies were supposed to coordinate operations with other units of the expedition. But on the morning of June 25, Custer found an Indian village and decided to attack on his own. In the ensuing battle, the Seventh Cavalry was overwhelmed: more than 200 troops, including Custer, were killed.

Brevet Major General George Armstrong Custer in field uniform.

Date 23 May 1865

Source Civil war photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Sitting Bull, Hunkpapa Lakota holy man and leader ca. 1883

David F. Barry, Photographer, Bismarck, Dakota Territory

For most Americans, Indian conflicts still existed, but they were a distant problem, not an existential threat to an industrializing nation of thirty million. So it was inconceivable for Americans to wake up one July morning, just days after celebrating the country’s 100th birthday, to learn that Indians in Montana had wiped out the famous general George A. Custer and 200 of his men. The whole country went through shared disbelief, grief, and rage. For Americans of that time, the U.S. Army’s defeat at Little Bighorn was as shocking as JFK’s assassination a century later.

… At the Rosebud, General Custer with twelve companies of cavalry, left Terry to make a detour around by the Little Horn. This was on the 22d of June. On the 25th he struck what was probably the main camp of Sitting Bull. He had pushed forward with greater rapidity than his orders directed and arrived at the point where a junction of the forces was intended, a day or two in advance of the infantry. Without waiting for the rest of the troops to come up, General Custer decided upon an immediate attack. The Indians were posted in a narrow ravine, about twenty miles above the mouth of the river… The Indians poured a murderous fire upon them from all sides, and not one of the detachment escaped alive. General Custer himself, his two brothers, his brother-in-law, and his nephew were all killed… A survey of the disastrous battle-ground disclosed a dreadful slaughter. Two hundred and seven men were buried in one place, and the total number of killed is estimated at three hundred and fifteen, including seventeen commissioned officers. The bodies of the dead were terribly mutilated. The Indians are supposed to have numbered from 2500 to 4000, and all the courage and skill displayed by our troops was of no avail against such overwhelming odds…

(From Harper’s Weekly, July 22, 1876, 598)

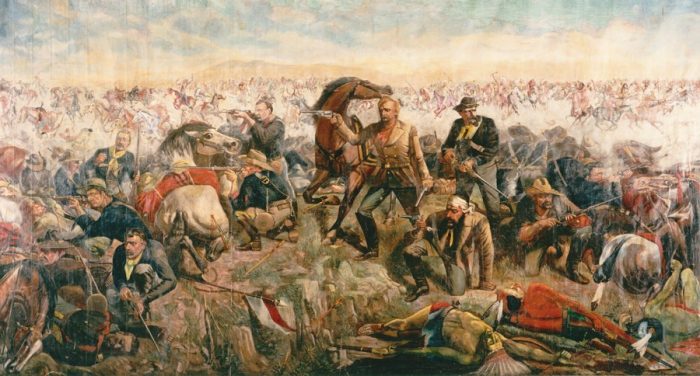

“Battle if the Little Big Horn” John Mulvany (1881) Private Collection/The Stapleton Collection/Bridgeman Images

Five years after the battle, John Mulvany completed the first major painting of it. His work toured the country for 17 years.

The experience of Custer and his men can be reconstructed only by inference. However, long-neglected accounts given by more than 50 Indian participants or witnesses provide a means of tracking the fight from the first warning to the killing of the last of Custer’s troopers—a period of about two hours and 15 minutes. In his 2010 book, The Killing of Crazy Horse, veteran reporter Thomas Powers draws on these accounts to present a comprehensive narrative account of the battle as the Indians experienced it. Crazy Horse’s stunning victory over Custer, which both angered and frightened the Army, led to the killing of the chief a year later.

Crazy Horse, (c. 1840 – September 5, 1877), a Lakota war leader of the Oglala band in the 19th century

Here he describes the “last stand” of Custer’s troops from the perspective of those who were there:

From their position on Calhoun Hill the soldiers were making an orderly, concerted defense. When some Indians approached, a detachment of soldiers rose up and charged downhill on foot, driving the Indians back to the lower end of Calhoun Ridge. Now the soldiers established a regulation skirmish line, each man about five yards from the next, kneeling to take “deliberate aim,” according to Yellow Nose, a Cheyenne warrior. Some Indians noted a second skirmish line as well, stretching perhaps 100 yards away along the backbone toward Custer Hill. It was in the fighting around Calhoun Hill, many Indians reported later, that the Indians suffered the most fatalities—11 in all.

But almost as soon as the skirmish line was thrown out from Calhoun Hill, some Indians pressed in again, snaking up to shooting distance of the men on Calhoun Ridge; others made their way around to the eastern slope of the hill, where they opened a heavy, deadly fire on soldiers holding the horses. Without horses, Custer’s troops could neither charge nor flee. Loss of the horses also meant loss of the saddlebags with the reserve ammunition, about 50 rounds per man. “As soon as the soldiers on foot had marched over the ridge,” the Yanktonais Daniel White Thunder later told a white missionary, he and the Indians with him “stampeded the horses…by waving their blankets and making a terrible noise.”

“We killed all the men who were holding the horses,” Gall said. When a horse holder was shot, the frightened horses would lunge about. “They tried to hold on to their horses,” said Crow King, “but as we pressed closer, they let go their horses.” Many charged down the hill toward the river, adding to the confusion of battle. Some of the Indians quit fighting to chase them.

The only survivor of the U.S. 7th Cavalry at Little Bighorn was actually a horse of mustang lineage named Comanche. A burial party that was investigating the site two days later found the severely wounded horse. He was then sent to Fort Lincoln, 950 miles away, to spend the next year recuperating from his injuries. Even though the horse remained with the 7th Calvary, it was ordered that he never be ridden again and be formally excused from all duties. The horse’s primary responsibility going forward was at formal military functions where he was draped in black, with stirrups and boots reversed, at the head of the Regiment.

Comanche eventually died at the age of 29 of colic on November 7, 1891. The officers of the 7th Calvary wanted to preserve the horse, so after the taxidermist completed the project, Comanche was put on display in the Chicago Exposition of 1893.Most Indians claimed that no one really knew who the leader of the soldiers was until long after the battle. Others said no, there was talk of Custer the very first day. The Oglala Little Killer, 24 years old at the time, remembered that warriors sang Custer’s name during the dancing in the big camp that night. Nobody knew which body was Custer’s, Little Killer said, but they knew he was there. Sixty years later, in 1937, he remembered a song:

Long Hair, Long Hair,

I was short of guns,

and you brought us many.

Long Hair, Long Hair,

I was short of horses,

and you brought us many.As late as the 1920s, elderly Cheyennes said that two southern Cheyenne women had come upon the body of Custer. He had been shot in the head and in the side. They recognized Custer from the Battle of the Washita in 1868 and had seen him up close the following spring when he had come to make peace with Stone Forehead and smoked with the chiefs in the lodge of the Arrow Keeper. There Custer had promised never again to fight the Cheyennes, and Stone Forehead, to hold him to his promise, had emptied the ashes from the pipe onto Custer’s boots while the general, all unknowing, sat directly beneath the Sacred Arrows that pledged him to tell the truth…

Every Cheyenne woman routinely carried a sewing awl in a leather sheath decorated with beads or porcupine quills. The awl was used daily, for sewing clothing or lodge covers, and perhaps most frequently for keeping moccasins in repair. Now the southern Cheyenne women took their awls and pushed them deep into the ears of the man they believed to be Custer. He had not listened to Stone Forehead, they said. He had broken his promise not to fight the Cheyenne anymore. Now, they said, his hearing would be improved.

(Adapted from The Killing of Crazy Horse, by Thomas Powers. Copyright © 2010. With the permission of the publisher, Alfred A. Knopf.)

The Lakota and Northern Cheyenne won the battle. But eight months later the United States won the Great Sioux War and confined to reservations nearly all their Plains Indian adversaries. Little Bighorn, however, never really ended. We are still trying to make sense, sometimes in strange ways, of a complicated and powerful history. And the country is still coming to terms with a hard and enduring reality: the United States was built at great cost to Native Americans.

Posted: 25 June 2019

-

Categories:

American Indian Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture