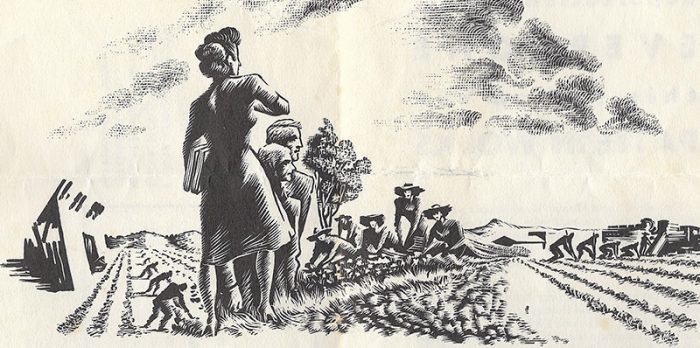

The work of many hands

We do our best work when efforts and ideas can flow across positions, titles, offices, and departments, when we value the work of every hand, when each person recognizes how their labor contributes to our larger mission.

For a historian like myself, Labor Day evokes a rich tradition of American labor activism. Earlier this year, our American Enterprise exhibition at the National Museum of American History included a case on the life of Luisa Moreno, a Guatemala-born civil rights activist and labor organizer. Throughout the 1930s and ’40s, Moreno advocated for immigrant laborers across the United States, bringing attention to overlooked issues around fair wages, workplace abuse, and more. In 1938, she brought together over 100 groups to form El Congreso de Pueblos de Habla Española, the Spanish-Speaking People’s Congress. Her story sticks with you, in part for her remarkable achievements and vision, but also for her approach to making change:

“One person can’t do anything,” Moreno said. “It’s only with others that things are accomplished.”

The FBI harassed her. The U.S. government deemed her an un-American communist. The Immigration and Naturalization Service nearly deported her. But Luisa Moreno dedicated herself to civil rights and to improving working conditions for laborers, especially Latinas. (Courtesy National Museum of American History)

Well, maybe the small tasks we can get done on our own. But for other, more ambitious endeavors, we all need some help. And at the Smithsonian, our ambitions are certainly grand. So, as we buckle back in for what’s sure to be a busy fall, I’ll remember her advice: the work that matters most happens in collaboration with others.

As a curator, a museum director, and now as Secretary, my career at the Smithsonian has been one of great visibility. But the moments I’m most proud of in my career—a key acquisition, a new exhibition, a museum opening—are due to those whose work is far less visible. Every day, a legion of creative, determined, talented individuals enable our core mission: to increase and diffuse knowledge.

This includes the people who ensure that doors are open and facilities safe for the tens of thousands of visitors we host each day; people who keep our grounds bright and lush; people who steer us through the nuanced legal structures of the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex; people who ensure that each one of us sees a paycheck at the end of the month; people who design, construct, and fabricate our stunning buildings; people who swoop in to save the day when a system crashes or equipment breaks; people who organize our acquisitions into exhibitions; people who show up in the snow or on federal holidays, when others of us have the day off; people who preserve and protect our most treasured objects. In sum, the whole village.

Most of this work isn’t flashy or readily apparent to the public. But it’s the backbone of this Institution.

One of the great joys of working at the Smithsonian is the opportunity to learn from our professionals across so many areas of expertise. The best education in my time as a curator was getting to know the specialists in collections, exhibitions, preservation, visitor services, and more. I’d open a drawer, not sure what it held, and someone would invariably step up and explain to me that I was looking at Lewis and Clark’s compass. They’d show me how to read it and understand it, describe how to preserve it and protect it, and most importantly, remind me not to drop it. (An important skill for any aspiring curator.)

In 1993, then-specialist Bill Yeingst and I traveled to North Carolina to collect the Greensboro Lunch Counter, the site of the historic, six-month long sit-in that led to the desegregation of the F.W. Woolworth lunch counter in 1960. This protest drew national attention and sparked the youth-led movement against segregation across the South.

On February 1, 1960, four African American college students sat down at a lunch counter at Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina, and politely asked for service. Their request was refused. When asked to leave, they remained in their seats. Their passive resistance and peaceful sit-down demand helped ignite a youth-led movement to challenge racial inequality throughout the South. (Photo courtesy of Greensboro News and Record)

A section of the Woolworth lunch counter from Greensboro, N.C., installed in the National Museum of American History. (Photo courtesy NMAH)

In Greensboro, Bill and I negotiated with the Greensboro City Council, employees of Woolworth, and representatives of the African American community for a piece of this lunch counter. I was dizzy with excitement, talking about the moment and the scholarship and the historical importance to the Civil Rights movement. It was Bill who connected that vision to action, leading conversations around transport, preservation techniques, and exhibition spaces. And during a follow-up trip, it was a broader set of Smithsonian staff who supervised the dismantling, crating, and transport of the counter back to Washington, DC.

I view this as one of the most important acquisitions of my life. It would not have happened without collaboration across all these different skill sets.

This process hammered home a lesson that I now see everywhere across the Smithsonian, from the security guards who lend me some morning verve to the maintenance staff who share with me their opinions about a new initiative. We do our best work when efforts and ideas can flow across positions, titles, offices, and departments, when we value the work of every hand, when each person recognizes how their labor contributes to our larger mission. That’s One Smithsonian in action.

About us: The Office of Facilities Management and Reliability

Posted: 10 September 2019

-

Categories:

Collaboration , Education, Access & Outreach , From the Secretary

I for one think that Secretary Bunch has already proven to be one of the greatest Secretary’s the Smithsonian has ever had. This, even though he has only been in his current position for a very short time. In many ways it’s not how much time you’ve spent in a position, what matters most is what you did while in that position (the uplifting and hope filled praise he gives to the many whom often never hear such words).

I was an Officer with The Office of Protective Services for over 15 years. It puts a smile on my face and in my heart when I hear Secretary Bunch mention the contributions of members of OPS. Then again, not only OPS does he mention, but other departments who are for the most part marginalized at the Smithsonian (but not anymore).

Thank you Secretary Bunch.

Peace and Blessings