Artist at Work: Jackson Tanner

His pointillist style and even his first name may evoke Jackson Pollack, but artist Jackson Tanner has developed his own unique mode of artistic expression. John Barrat profiles one of our Smithsonian colleagues whose work is on display in the Artists at Work exhibition.

“When people first see my paintings, many of them assume I must use a very tiny triple 000 paint brush to cover a canvas in tiny dots,” says Jackson Tanner, a supervisory collections manager at the National Museum of African American History and Culture and longtime artist. “But that would take forever! Some of my paintings are as large as 36 x 72 inches and I like to consider myself still sane.”

Still, he says, his works are created entirely by hand with basic painting tools—no automated presses or pneumatic processes. “I just figured out how to make a whole bunch of dots at one time. If I had to compare how I do it with a technique, I’d say it is very similar to what Jackson Pollock was doing, I just use a different set of tools.”

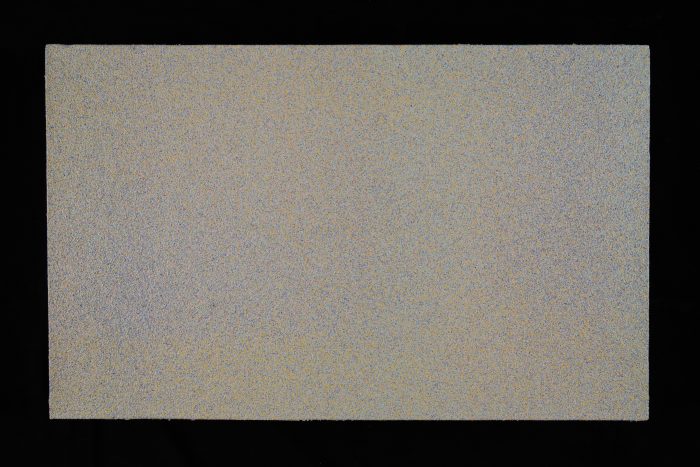

“Galazios ourranos” April 2018

G. Jackson Tanner

Golden Fluid Acrylic

One of Tanner’s paintings “Galazios Ouranos (Blue Sky)” is now on view in the S. Dillon Ripley Center in “2019 Artists at Work,” a juried exhibition of artworks by Smithsonian staff. “The unique paint application creates a surface texture that is inviting to our tactile natures, as though it wants to be touched,” its caption, written by Tanner, explains.

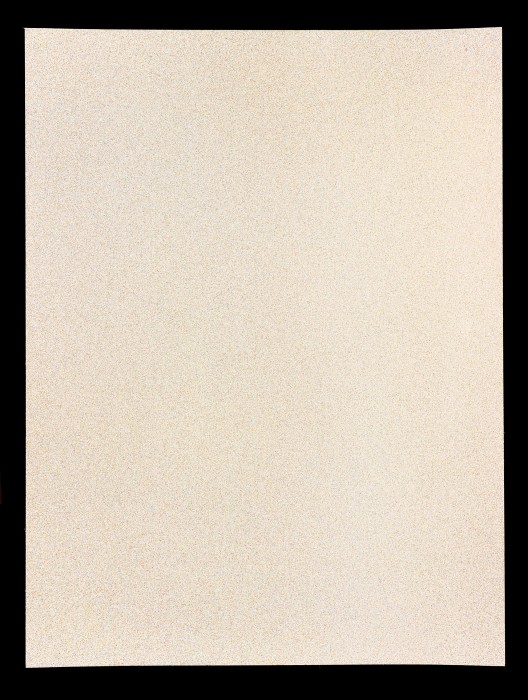

“Galazios ourranos” April 2018

G. Jackson Tanner

Golden Fluid Acrylic

“I control every transition of color in my paintings by building multiple chromatic layers—as many as 50 different layers—to create the image that you see,” Tanner says. “This repetitive process produces highly complex color fields that overlap and work together to evoke the sense that the image could have been manufactured through a mechanical automated process.”

“I tend to be a very instinctual, visual painter. I come up with some ideas and concepts, but I just generate these dots with regular painting tools.”

After studying at the Art Institute of Chicago and earning an art degree at the University of Illinois, Jackson’s early work in the 1980s was much different: he used oils and his work was more figurative.

It was while refurbishing a house in Delaware in 2011 that the concept for his dot-filled paintings planted itself in his imagination.

“One thing leads to another, discounts are offered on building materials you need and not necessarily in any logical order, so I put down floor before I had the walls done,” Tanner recalls. “I then painted the walls and ended up with a lot of dots all over the floor and it just kind of stuck with me.”

“Ashes to Ashes” by G Jackson Tanner, Supervisory Collections Manager, National Museum of African American History and Culture. Acrylic, 2012.

“Soon after that my daughter was born, and while I was home on paternity leave, I got to thinking that as she’s sleeping there’s stuff I could do. So, I went out into the garage and kind of figured out how to do it on a larger scale.”

Tanner’s tactile art has been likened to pointillism, he says, were small dots of color are put down in patterns that form a representational image. But his work is distinctly different. “Pointillists purposely take colors on the end of a brush and put two specific colors next to each other, so your eye would blend together a blue and a yellow dot and from a distance see green,” he says. “I sort of do that, because my dots end up next to each other obviously. But, when I’m choosing a color, I think more in terms of a layer of dots in an area. I make stencils to block out areas. So, I’m focusing on the area that I’m trying to put dots down on in a new layer. Looking at what is the overall color coming back and choosing colors in that manner.

“What I’m doing might also be compared to a real high-end woodcut or linocut printer that is creating 15 or 20 different color layers,” he adds.

One practical aspect of Tanner’s paintings that has benefited from his employment at the Smithsonian is their durability. “I’ve long had access to various conservators and I just kind of gleaned a lot of information over the 20 years I’ve been working at SI,” he says.

To hold his paints Tanner uses sturdy panels called apple-ply, which consist of 13 layers of maple hardwood that is three-quarters of an inch thick. He also uses high quality Golden Artist paint and the powder-coated frames are made by journeymen metalworkers.

Jackson Tanner in his studio. (Photo by Vanessa Pham @ https://www.vanessapham.com/)

When talking about his progress and evolution as an artist Tanner mentions a letter written by painter Sol Lewitt to fellow artist Eva Hesse. Hesse was having a kind of “painter’s block,” Tanner says, and in Lewitt’s letter he tried to inspire her by saying something like “Just go out and create. Sometimes you just have to make bad art.”

“That really was kind of what was going with me at one time,” Tanner recalls, and a friend said to me something very similar, and I was like, ‘Well, OK.’ And I started going out to Home Depot and Lowe’s and buying rejected home paints and using them. That’s when I learned to generate all these dots,” Tanner says. “That was my purpose, to literally go out and make some bad art. And then I got good at it.”

“Now I am making some really interesting highly detailed images which I hope everyone else thinks are great too, and if I have to keep answering that same question of how do you do that, with a really small brush? I’ll just keep rolling with the punches and giving out clues to help them figure it out” and then we can both have a great laugh together when the big reveal is finally made.”

Posted: 9 January 2020

- Categories: