Thinking about impeachment like a historian

This week, the third impeachment trial of a sitting U.S. president is unfolding. Amelia Grabowski, acting social media manager at the National Museum of American History, spoke with with political history curator Jon Grinspan about how historians look at impeachment.

What is impeachment?

Impeachment is actually a vote to put the president on trial, not a trial or a conviction. The sitting president can be impeached for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors,” as defined in Article 2, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution. Conviction and removal from office, following an impeachment trial, has never happened.

And what about President Richard Nixon?

“The mechanisms were going with Nixon to impeach him,” Grinspan explained. But Nixon stepped down before the vote to impeach (that is, the vote to put him on trial—not the vote to remove him from office).

In U.S. history, two other presidents have been impeached: Andrew Johnson in 1868 and Bill Clinton in 1998.

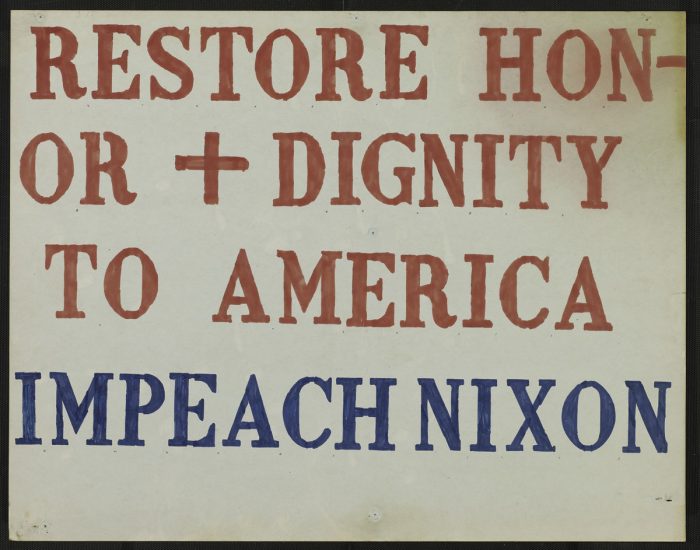

Several protest posters in the collections of the American History Museum include calls for impeachment. Impeachment has happened so rarely in U.S. political history that some mistake “impeachment” for removal from office—when it actually means to vote to put on trial.

Impeachment marks a unique moment that shifts how the U.S. government is normally structured.

“The whole point of our architecture of a system of government is separation of powers. . . . They’re supposed to balance each other out to prevent tyranny,” Grinspan said. “But this is one point where there’s a clash in powers. All the powers suddenly are involved: the House votes for impeachment, the Senate has a trial, the chief justice of the Supreme Court runs the trial, and the president is on trial. All the sudden, all these carefully balanced checks and balances come crashing into each other.”

Robe worn by Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist during the impeachment trial of President William Clinton. Rehnquist added the gold stripes to the sleeves a few years earlier after seeing the costume worn by the Lord Chancellor in a production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s “Iolanthe.” (Courtesy National Museum of American History)

What do we learn when we look at impeachments (and Nixon’s near-impeachment) together?

“Every impeachment is a microcosm of a larger cultural conflict,” Grinspan said.

“The Johnson impeachment is about Reconstruction, the future of the country after the Civil War, and race in America,” Grinspan said.

After the Civil War, the Radical Republicans in Congress championed an ambitious plan of Reconstruction that aimed to both end slavery and secure the civil rights of African Americans nationwide. Johnson, in contrast, supported a much more lenient plan for reintegrating Confederate states back into the Union. Under Johnson’s proposal, former Confederate states had free rein to institute Black Codes—laws that maintained white supremacy by stripping formerly enslaved African Americans of many of their hard-won freedoms. As president, Johnson used all the powers of his office to oppose Congress’s efforts to push Reconstruction in a more transformational direction.

While Johnson’s high crime and misdemeanor (which allowed Congress to bring articles of impeachment) specifically revolved around his firing of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Grinspan said, tensions over race and Reconstruction is “what gets Congress and the presidency to go at it with each other.”

“Johnson and Congress are in this huge feud. A lot of the feud turns on who holds offices—the former people under the Lincoln administration, including Edwin Stanton, or can Johnson put up his new people who will follow his line more,” Grinspan said. “Congress puts a trap where they made it illegal to fire Edwin Stanton, and when Johnson fires Stanton he steps right in that trap.”

This ticket to President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment trial tells both the story of the impeachment and post-Civil War life in Washington, D.C. D.C. blossomed into a bustling city during the Civil War. “It’s also this point where D.C. has its own society, and so everyone is trying to be seen there—there are all these prominent public figures and activists,” Grinspan said. “They made 800 tickets and there was a huge war in D.C. to try to get into the trial.” It’s another way the story of Reconstruction is playing out in the Johnson impeachment trial. (Courtesy National Museum of American History)

Even though Johnson was never removed from office, his story provides an example of how impeachment can leave a lasting impact on a presidency and his agenda. After Johnson’s impeachment, “Congress is able to usher in their vision of Congressional Reconstruction, where you get things like African American voting rights and African American citizenship,” Grinspan said, including the Fifteenth Amendment.

This 1870 lithograph celebrates the rights and opportunities that African Americans stood to gain under the Fifteenth Amendment, part of Congress’s Radical Republicans’ vision of Reconstruction.

In the 20th century, we again see how impeachment can reflect larger cultural clashes. Nixon’s potential impeachment reflects what was going on in the nation at that time.

At a time of massive protest, “Nixon is obsessed with protestors and he’s obsessed with the idea that there is dissent,” Grinspan said. “There’s a climate of paranoia and that’s what prompts his illegal action.” The House was considering impeaching Nixon for misdeeds including break-ins, unauthorized wiretappings, hush-money payments, and wrongful use of the Internal Revenue Service.

But even Nixon’s actions reflect the era.

“Dirty tricks make sense during the Cold War,” Grinspan said. “They’re doing dirty tricks all around the world. They’re doing them in Vietnam, and Iran, and Guatemala.”

Nixon’s pending impeachment is often pointed to as the beginning of an era of distrust in government, but it is a key episode in a process of losing trust that started long before, Grinspan explained.

The Nixon administration established a secret-operations unit known as the Plumbers. On September 3, 1971, they broke into the office of Dr. Lewis Fielding, Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist. They were looking for damaging information against Ellsberg, who had leaked Pentagon papers concerning the Vietnam War to the press. This file cabinet was damaged in the search. It was the first in a series of the Plumbers’ break-ins—including the famous incident at the Watergate.

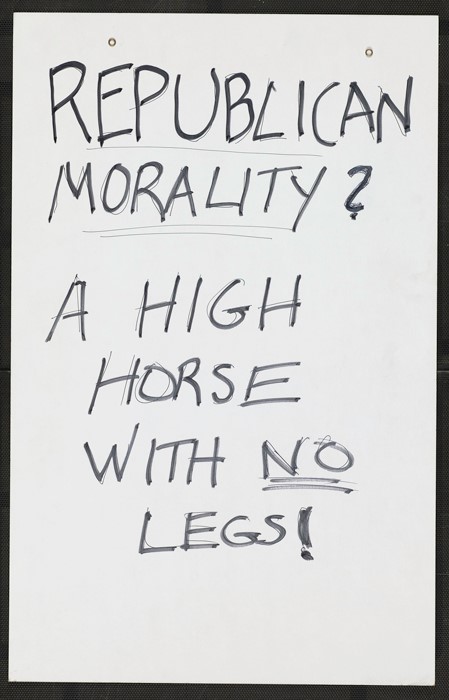

According to Grinspan, Clinton’s impeachment reflects the culture wars of the 1990s, where “there’s this conservative ‘family values’ Congress that suddenly has a lot more power versus this president who is seen as this permissive, relaxed, baby-boomer guy.” Clinton was impeached with charges of perjury and obstruction of justice stemming from the president’s testimony in a civil suit and whether he misrepresented his relationship with a White House intern.

This pro-Clinton poster pokes fun at the conservative response of Republican members of Congress to Clinton’s indiscretions.

Grinspan and other curators at the museum are following the impeachment proceedings of President Donald J. Trump closely. Again, it provides insights into larger national issues.

“The actual concrete thing the whole impeachment is about is partisan campaigning,” Grinspan said. “That’s what President Trump is accused of doing—using federal power to fight a personal campaign.”

As events unfold, curators will determine which objects best represent this historic moment, for inclusion in the national collection. Contemporary collecting allows us to ensure this story can be told in the future. For instance, some of the objects above were collected during previous impeachment proceedings. This is one way in which the museum actively engages with the history, spirit, and complexity of the United States’ democratic experiment: by collecting, documenting, and sharing the U.S. political system, including presidential history.

This post was originally published by the American History Museum’s blog, “O Say Can You See?”

Posted: 23 January 2020

- Categories: