Collecting today for tomorrow

Our obligation to future generations is to ensure that when they seek the lessons of transformation and resilience from our moment, they have the record to do so.

In a period of deep instability, I have been searching for precedent. For many of us, the clear analogue is the Civil Rights movement of the ’60s: the buses and boycotts, the March on Washington, the uprisings in cities across the country, the Poor People’s Campaign of ’68.

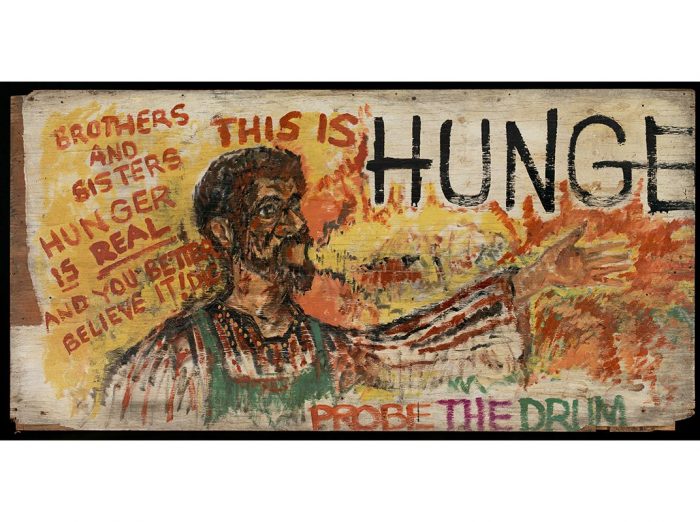

Jesse Jackson address the crowd at Resurrection City during the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968. (From the collections of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, gift of Gift of Robert and Greta Houston © Robert Houston)

There’s a story about this time that we hear a lot at the Smithsonian. How in 1968, despite concern from those around him, Secretary Ripley opened the doors of the Smithsonian up to protesters of the Poor People’s Campaign to make our buildings places of rest and recuperation. Like all stories that we choose to remember, this one tells us a great deal about who we hope to be and how we want to serve our public as an Institution.

During tumultuous times, it is easy to find guidance and comfort in the stories of those times the Smithsonian got it right. But just as important, I think, are the times when we didn’t. When our staff and our public pushed us to learn and to grow, to become better stewards of our past and better storytellers for our present.

When the Museum of History and Technology (now the National Museum of American History) opened in 1964, many staff were frustrated by the lack of African American representation in the museum. As curator emeritus Harry Rubenstein points out, this reaction was compounded by what these staff felt was a failure of the Smithsonian to collect or address the March on Washington, only one year prior.

A mural salvaged from “Resurrection City”, the encampment on the National Mall created by the Poor People’s campaign of 1968. The mural is now on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

A painter creates a mural on the boarded-up windows of the Park at 14th nightclub in Washington, D.C., on June 6. (Toni L. Sandys/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

As a former curator who has often felt stymied by a dearth of items from such a consequential event in our collections, I have always been drawn to the story of curator Keith Melder, who passed away in 2017. I knew Keith when I first worked at NMAH in the late ’80s. In 1968, driven in part by what they saw as a botched response to the March on Washington, a group of staff from the museum including Melder and photographer Clara Watkins took the initiative to collect the Poor People’s Campaign that was camped on the museum’s doorstep. They gathered banners, placards, and murals, collected pieces of tents, and took photographs.

Because of the creativity and conviction of these individuals, the Smithsonian boasts a robust archive that can convey the story of the Poor People’s Campaign and Resurrection City. In the decades since, this vital trove has been used in exhibition after exhibition to share an essential piece of American history.

As thrilling as it is to see Harriet Tubman’s shawl or Abraham Lincoln’s top hat, we know that the role of museums isn’t just to acquire and celebrate those items already venerated in history. We also recognize that history happens around us; that we collect today so that we can tell the story tomorrow. There have been so many times in my career when we didn’t have the necessary objects to tell a story that I wanted to. And at this critical juncture in American history, the need to collect and interpret is especially significant.

That’s exactly why I’m so thrilled by the collaborative collecting efforts we have going on right now. A joint effort between ACM, NMAAHC, and NMAH to collect a cross-section of items from the protests today will be a vital resource in the future: Homemade protest signs collected from outside the White House, personal protective equipment from participants, and the voices of the people who have made this moment a movement. Each piece can tell a unique story and offer a window into what I hope future generations will view as an inflection point in American history.

Our impulse in this moment has been to look back. To find lessons from 1918 or 1968, to seek inspiration from the past to help us move forward. Our obligation to future generations is to ensure that when they too look back, when they seek the lessons of transformation and resilience from our moment, they have the record to do so.

The historical details about the Smithsonian rely on research by Harry Rubenstein, curator emeritus at the National Museum of American History.

Posted: 30 June 2020