Your IMPACT | Your Smithsonian: Healing a Nation

Race, Community and Our Shared Future

In a year marked by widespread protests against racial injustice and calls to reckon with America’s racial past, the Smithsonian is taking a big step toward helping the country heal. A new initiative, Race, Community and Our Shared Future—launching nationwide this winter with generous support from founding partner Bank of America—will explore how Americans understand, experience and confront race.

The initiative is an ambitious commitment to the nation that will draw on the full breadth of Smithsonian expertise, research and collections. Through virtual town hall conversations, in-person and digital exhibitions, film screenings, teacher training programs and more, the Smithsonian will provide context and tools for Americans to talk openly about their personal experiences of race and take action against racism and intolerance.

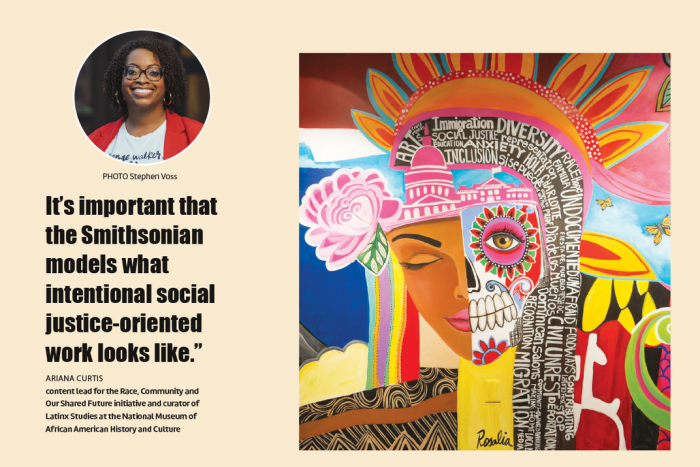

We sat down with Lonnie G. Bunch III, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and Ariana Curtis, content lead for the initiative and curator of Latinx Studies at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, to discuss the Smithsonian’s unique ability to address race in America and define a more hopeful future for all of us.

Why is it important for the Smithsonian to lead a national conversation on race and identity at this moment?

Lonnie Bunch: At a time when the nation is in crisis, all of our institutions need to contribute to making the country better. The Smithsonian is a place that is trusted, and it’s also a place that has expertise—scholarship and collections on issues of race. This is an opportunity for the Smithsonian to demonstrate that it is of value, not just as a place that looks back but as a place that looks forward. We will do everything we can to provide understanding and contextualization as the country tries to better understand who it once was and point it toward who it can become.

Ariana Curtis: I second that—the Smithsonian is unique as a trusted national and international institution. We need to use our collections and scholarship to provide the necessary historical context. At the National Museum of African American History and Culture, we tell the unvarnished truth. That extends beyond just one museum to who we are as a country and who we have been. This is the moment to use our public trust. There is a great desire to understand our current moment as a consequence of history and how we support each other collectively moving forward. We can lead in that way.

Bunch: The country tends to live in bubbles. We talk to the people we think we understand. The Smithsonian can bring together people who don’t normally talk to each other. That ability to blur boundaries is what’s special about the Smithsonian and why this initiative is so important.

How will this new initiative change the Smithsonian, both internally and externally?

Curtis: The Smithsonian is a great convener but it is also a value leader. People believe us and they believe in us. It’s important that the Smithsonian models what intentional social justice-oriented work looks like and reaffirms that this work is critical for museums and cultural centers. This is part of who we are. A lot of our engagement has centered on people coming to Washington, D.C., or to other Smithsonian spaces. This is an opportunity to rethink how we operate and collaborate. We want to co-create with local communities and co-lead discussions about the world. The Smithsonian always should take the dual role of educator and learner.

Bunch: I’ve spent my career pushing institutions to be fair and more inclusive. I think the Smithsonian has done wonderful work in some areas but really needs to be a model for valuing diversity and inclusion. This initiative shines a light on all our dark corners. It’s going to be uncomfortable. It will make us grapple with big questions. One of the things I want to do is put together a scholarly anthology that looks at how the Smithsonian has dealt with interpreting race and how we have been affected by the racial attitudes of the day. At the installation ceremony when I became Secretary of the Smithsonian, I thought about how Frederick Douglass wasn’t allowed to speak at the Smithsonian. At that moment, I felt that Douglass was speaking now that I was there. If we understand who we once were, we can use that to propel us forward—to be a model for how cultural institutions treat their own staff.

How will this initiative reach and have impact on communities across the country?

Curtis: We want to reach communities where they are. Scholarship and collections are our strengths but our conversations need to have a deep, local resonance for people to understand how issues of race impact their lives. We will start with town hall conversations across the country. We want these to be a dynamic mix of local and national activists and educators. We will have people skilled at providing frameworks talking to people who have place-based knowledge. We want to grow engaged, intergenerational communities of learners and doers. We want these conversations to spark community involvement and a sense of purpose.

Bunch: This is the moment for museums to be of value. At a time when people are fearful, it’s the role of a museum to give comfort. At a time of pain, museums can remind us of beauty. We can help communities grapple with the things that scare them, that divide them. Part of our collaboration will be creating an environment where museums recognize they have this greater role. This initiative will also give us a chance to take full advantage of programs like the Smithsonian Affiliates and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES). I’ve spent a lot of time in museums and cultural institutions across the country. Often, we don’t take full advantage of what these partners bring to the table. I don’t think we can get to the local conversations without drawing on their expertise.

How can the Smithsonian improve education on issues of race and identity?

Bunch: One of the Smithsonian’s major platforms is education. We realize that there is great interest in understanding how to use education to reshape the way race is taught in elementary school, or how to make sure educators are comfortable talking about race. We have a great array of material on these issues, but we should also illuminate the good work on education being done at places like Harvard or in the District of Columbia, for example.

The Smithsonian’s greatest success will come as a network collaborator. We should be a portal—a place to draw on the best thinking on education and race, adding our own expertise to help the public grapple with these issues.

Curtis: The Smithsonian can move the conversation beyond individual racial identification to talk about structural racism and how race operates. We think about race from multiple perspectives, from the individual to the institutional. The resources we provide help set that framework, so people understand the power of race and how justice is collective.

What does this institutional commitment to explore race mean to you on a personal level?

Bunch: It’s personal in terms of saying: A country is in crisis—how do I help? It’s also personal because I am someone who has experienced the kinds of issues that have been shaped by race in this country. This is an opportunity to give back. It is our responsibility—as scholars, educators and cultural leaders—to help the country. By doing that—I hope—we will make sure that my grandson won’t get thrown over the hood of a police car like I did at age 14. It should be personal for all of us.

Curtis: I know I’m lucky to have the Smithsonian career that I have, from a personal and professional standpoint, as a Black Latina scholar and as a curator. I am lucky in the timing. Previously, spaces like the Smithsonian were not available to someone like me. I know that a series of institutional commitments made my career possible. I have benefited from the Latino Curatorial Initiative and the building of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. I understand how institutional commitments can be life changing at an individual level. I get excited imagining the transformative impact of a long-term commitment like this and its legacy on the Smithsonian, the museum field, for our visitors and for future museum professionals.

This post by Abigail Croll and Julia Ross was published November 2020 in IMPACT Vol. 6 No. 3 and republished by the Smithsonian magazine blog, Smithsonian Voices.

Abigail Croll is a graphic designer, photo researcher and content manager and Julia Ross is a writer, editor and communications specialist for the Smithsonian’s Office of Advancement.

Copyright 2020 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.”

Posted: 30 November 2020

-

Categories:

Collaboration , Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories , History and Culture