Solomon Brown’s Verses and Vision

A country creates its history not only by what it chooses to remember but also by what it chooses to forget. As we strive to tell more complete stories of this country’s history, we at the Smithsonian must reflect on our own past, as well. Here is the story of a man of unique and wide-ranging talents: Solomon Galleon Brown, the Smithsonian’s first African American employee.

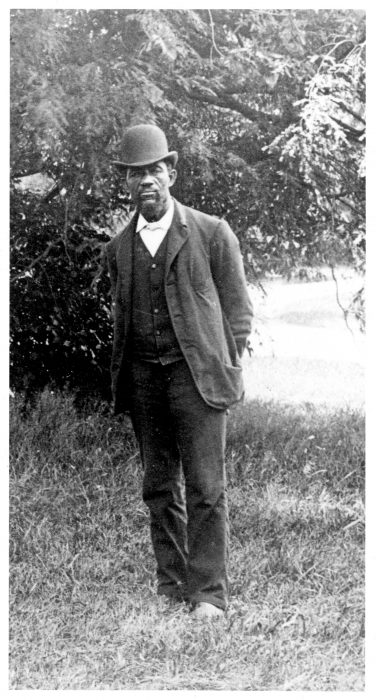

Today’s Smithsonian Castle, a frequent entry point to families planning their visit to the Smithsonian, has changed quite a bit in form and function since its inception. In the 1870s, for instance, the Castle provided the living quarters for the Smithsonian’s first Secretary, Joseph Henry, his family, and the burgeoning taxidermy collections. While staff battled an ensuing rat and flea problem (not to mention a lovely odor), Undersecretary Spencer Baird and his associates worked in offices on the first floor of the East Wing. (Baird, the prolific naturalist and collector who was responsible for those tempting specimens, would eventually become Secretary upon Henry’s death in 1878.) Among these associates, in an adjacent office, worked a man of unique and wide-ranging talents: Solomon G. Brown, the Smithsonian’s first African American employee.

Lonnie Bunch, Secretary of the Smithsonian, has written that “You can tell a great deal about a country and a people by what they deem important enough to remember… Yet I would suggest that we learn even more about a country by what it chooses to forget.”

The same, I think, is true of the Smithsonian. As we focus on our commitment to tell more complete stories of this country’s history, we must reflect on our own past. What aspects of Smithsonian history do we choose to remember, and what have we overlooked?

As large as Henry and Baird loom in early Institutional history, Brown’s tenure at the Smithsonian dwarfed both of theirs. He retired in February of 1906 after 54 years of employment. During this time, he’d served in roles that spanned the Transportation Department, the International Exchange Service, the Zoo, and the Bureau of American Ethnology as a laborer, a clerk, a registrar, an illustrator, a lecturer, and more.

As he wrote to Baird in 1862, ten years after he’d joined the Institution, “I have engaged in almost every branch of work that is usual and unusual about the S.I.”

A true Renaissance man, Brown’s talents in science, administration, and civic leadership were matched by his skill in poetry. Throughout his later decades, Brown’s poems frequently appeared in the Washington Bee and other newspapers aimed at the African American community. I am particularly interested in Brown’s poems for the insight they offer into the growth of the young Smithsonian, the successes and challenges of a talented black man, and the ways that we remember each.

“50 Years Today”

Brown wrote “50 Years Today” in 1902, commemorating his five decades at the Institution, the changes he’d witnessed, and those who’d shaped his time here. The poem opens with a panoramic view of people and moments across those decades:

‘Mid all the changes I have seen

Since fifty years have rolled between,

My eyes can rest on only few –

Whose faces once could daily view,

And kindly greet in passing.‘

Throughout the poem, Brown celebrates “all the changes” at the Smithsonian—massive trees growing from seeds on the Mall, the creation of the Fish Commission and the Weather Bureau, and a new National Zoo. Among all those “whose faces once could daily view,” Brown eventually singles out two for particular praise: Henry, “a man whom all regarded,” who first hired Brown, and Baird, a chief of “justice, truth and grace; a scientist of great renown,” with whom Brown forged a particularly close relationship.

Born free in 1829 near what is now 14th and U streets, N.W., Brown was apprenticed to a clerk in the D.C. City Post Office when his father’s death left the family destitute. At age 15, he secured a position in the post office as a technician, helping Joseph Henry, Samuel Morse, and Alfred Vail install wiring for the first telegraph line from Washington to Baltimore. This connection with Henry ultimately led to Brown’s hiring in 1852 as a general laborer at the Smithsonian, three years before construction of the Castle was completed. “A man of pious, Godly fear / Affording all his friendly care; / ‘Twas he who first appointed me,” Brown wrote of Henry in “Fifty Years Today.”

Despite this friendliness toward Brown, Henry (along with some other Smithsonian leaders) expressed attitudes deeply hostile toward African Americans. Henry considered African Americans a “child race,” unsuited to intellectual pursuits. On the Board of Regents at the time was Roger Taney, the Chief Justice who authored the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, which held African Americans “so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” So too on the Board was Henry’s close friend Jefferson Davis, future president of the Confederacy.

In this profoundly inhospitable environment, Brown built a name for himself. Although “Fifty Years Today” focuses largely on the work of others, Brown contributed significantly and rose quickly in his first decade. The progress and growth of the Smithsonian that the poem describes (“improvements seen on every hand”) seem to parallel Brown’s own life during the 1850s, ‘60s, and ‘70s: a steady, upward path toward leadership and status across a remarkable variety of fields and interests.

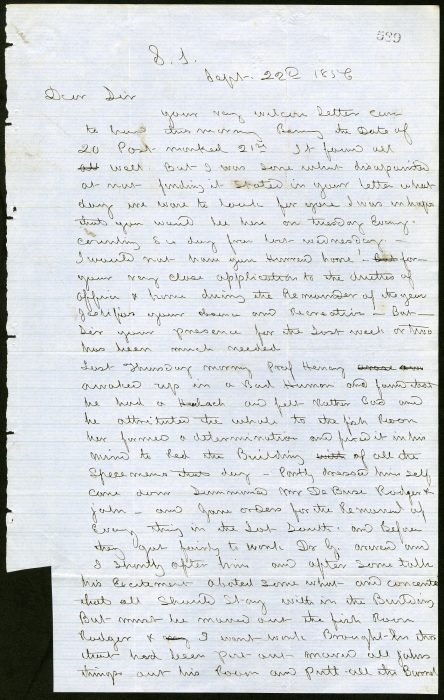

By the 1860s, Brown was supervising teams of both black and white workers, negotiating with Secretary Henry for pay raises, and taking on a wide portfolio of tasks, including managing collections and illustrating scientific lectures. Brown’s advancement was aided by the close relationship that he cultivated with Baird, becoming indispensable as Baird’s “eyes and ears” when Baird was away from the Smithsonian. The two corresponded closely; much of what we know about the day-to-day goings on of the Institution during this period comes from Brown’s letters to Baird.

Brown’s rise at the Smithsonian matched his rise in the Washington community and local politics. In the 1860s, Brown served on the Board of Trustees of Colored Schools, the newly established primary schools for black children. He became superintendent of both the Pioneer Sunday School Association and the North Washington Mission Sunday School, and later a trustee of Wilberforce University, the country’s first college owned and operated by African Americans. Before Congress abolished home rule in the District, Brown was elected to serve three consecutive terms on the DC House of Delegates, representing both black and white Anacostians from 1871-74.

“He is a Negro Still”

Yet while “Fifty Years Today” often serves as the official record of Brown’s years at the Smithsonian, the poem elides significant and tragic aspects of his life. Brown himself acknowledged this story as incomplete; as he wrote in the final stanza of the poem, “much has passed I have not told.”

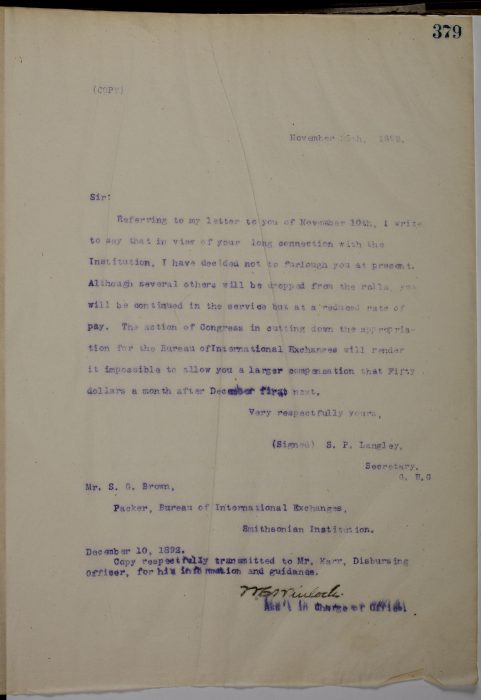

As the promises of Reconstruction fell to the rising discrimination of Jim Crow, so too did Brown’s position at the Smithsonian deteriorate. Secretary Baird’s death in 1887 led to the election of a new secretary, Samuel Langley. In 1890, despite Brown’s decades of experience at the Smithsonian, Langley stripped Brown of his senior duties and sent him back to the basement of the Castle to the ranks of common laborers.

In 1891, Brown wrote a poem called “He is a Negro Still” that describes the oppression facing African Americans across the country, and likely captures his feelings about his demotion:

They are very good to scrub and sew,

And do our kitchen work below;

To raise them up—we never will—

But keep them down as Negroes still…

Suppose he has inventive art,

The world acknowledge he is smart,

Intelligent and fills the bill?

He’s nothing but a Negro still.

This second stanza voices Brown’s experiences in his later years at the Smithsonian, relegated to the work of a laborer in the basement rooms beneath the Castle. A significant pay decrease in 1892 also sent Brown into serious financial difficulty and meant that he couldn’t afford to retire. Rather, he worked another 14 years in this reduced role. Brown died at his home on Elvans Avenue (now Elvans Road) four months after his eventual retirement in 1906, only blocks away from where the Anacostia Community Museum now stands.

Although “He is a Negro Still” traces the anger and disappointment of Brown’s experience, it ends with a declaration of pride:

Twist and turn it as you may

the Negro’s here, HE’S HERE TO STAY!

As it expresses triumph and hope, this line also brings to mind key questions about the ways in which we engage with our past. Who stays with us? What stories do we carry forward?

“Long may their fame be honored,” Brown wrote of Henry and Baird in “Fifty Years Today.” If the statue of Henry that stands proudly in front of the Castle’s entrance is any indication, we do well by this goal. And in some ways, Brown too has stayed with us: the book of his poetry at the Smithsonian Archives, compiled by Anacostia Community Museum employees, the Solomon G. Brown conference room, located at the top of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and a tree planted outside the National Museum of Natural History.

“But many facts are yet untold,” Brown wrote in that same poem, “to be revealed by others.” Although this statement reads mildly, I hear an implicit and equal charge, a reminder of our responsibilities in this month and throughout the year. As we celebrate Brown’s legacy, his verses impress upon me the obligation to grapple with difficult and uncomfortable aspects of our past, to read poems of promise and poems of pain, to remember and share Smithsonian stories fully.

Want to know more about Solomon Brown? Discover more in the Smithsonian Institution Archives and at the Anacostia Community Museum.

This piece relies on research from the Smithsonian Institution Archives, Louise Daniel Hutchinson and Gail Sylvia Lowe (Anacostia Community Museum), Terrica Gibson (Smithsonian Institution Archives), and Richard Stamm (Smithsonian Castle Curator).

Posted: 12 February 2021