Reading the rainbow: The origins of the pride symbol

GVGK Tang takes us on a fascinating journey through literature, film and politics to trace the origins of the iconic rainbow flag.

In 2017, in response to a slew of racist incidents in the “Gayborhood” area of Philadelphia, activists added black and brown stripes to the traditional six-color LGBT rainbow flag. The backlash was severe. Many rejected the alteration of such a supposedly sacred symbol. Apart from failing to recognize the intersectional interests of queer and trans people of color, critics invoked the rainbow flag as something constant and abiding. You can’t just change it! Or can you?

Of course, the rainbow as a symbol has appeared in many places and in many forms over the past century. Where did the so-called “pride” flag come from anyway? I went on a research journey to find out, exploring works of fiction, newspaper articles, autobiographies, political parties, rock bands, a certain Technicolor movie, and more. Here are the highlights of what I learned about this colorful, often-changing symbol.

The origin myth

Queer iconography once included pink and black triangles—re-appropriated by the LGBT community after the Nazis used them to label gay men and lesbians in concentration camps—and the labrys—a double-headed ax associated with the mythological, matriarchal Amazons. A Los Angeles Times article recently dispelled the popular belief that artist Gilbert Baker was solely responsible for the design of the symbol that came next—the rainbow. In collaboration with other volunteer members of San Francisco’s 1978 pride parade decorations committee—among them tie-dyer Lynn Segerblom (also known as Faerie Argyle Rainbow) and seamster James McNamara—activists departed from the most popular queer symbols of the time to create the original, eight-color flag (complete with pink and turquoise stripes).

Novel metaphors

So the rainbow has only been a queer symbol for the past 40 years? Not necessarily. Even a quick perusal of historical LGBT periodicals and magazines reveals a plethora of colorful references as far back as 1915, many of them in fiction writing. The chronology begins with D.H. Lawrence’s The Rainbow, featuring a lesbian affair between a student and a schoolteacher. Nadia Legrand’s 1958 The Rainbow Has Seven Colors features another lesbian May-December love, though an unrequited one. In both novels, the rainbow symbolizes new beginnings, different stages in life, and the gradations of time itself.

Everyday stories

Queer rainbow symbolism continued in the form of short stories—though it is hard to say who influenced whom or, indeed, if some simply claimed the rainbow independently as a symbol of their desires. Two short stories appeared in The Ladder, a lesbian magazine published by the Daughters of Bilitis (the first lesbian organization in the United States)—”End of the Mixed-Up Rainbow” by Diana Sterling in 1961, and “The Christmas Rainbow” by L.A.L. in 1962. Sterling’s work is slice-of-life, recounting the Sunday morning musings of two lovers. She uses vivid color imagery to evoke quotidian details and draw an extended metaphor. Meanwhile, L.A.L. tells of true love and tragedy, the rainbow taking on a particularly personal and aspirational meaning. The story concludes:

“… to those of you who have found your Christmas rainbow, we extend a sincere hope that it will remain yours for always. To those of you who still may search, we extend the hope that you may be very close to attainment.”

Diana Sterling, “End of the mixed-UP Rainbow,” 1961.

Friends of Dorothy

One might be quick to point out the significance of the song “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” from the 1939 classic film, The Wizard of Oz. “Friend of Dorothy” has proliferated as slang for being a gay man. Some historians have attributed its origin to the publication of the original turn-of-the-century children’s book series—their diverse characters (the dandy lion and Polychrome, a fairy princess and daughter of the Rainbow) and themes such as inclusivity. Others have pointed to the Technicolor film and its star, Judy Garland—a queer icon in her own right. The rainbow as a symbol of hopes and dreams remains as significant as ever 80 years after the movie was in theaters and 118 years after L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was published, in the lyrics of the poignant song “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.”

“Somewhere over the rainbow way up high

There’s a land that I heard of once in a lullaby.

Somewhere over the rainbow skies are blue

And the dreams that you dare to dream really do come true.”“Over the rainbow” Harold Arlen with lyrics by Yip Harburg, 1939

Headlines and headliners

Meanwhile, an article in The Advocate recounts a nonfiction, newsworthy moment featuring a rainbow. At a 1971 sex law reform rally in Sacramento, California, several speakers noted the appearance of a rainbow ring in the sky. Among them, Assemblyman John L. Burton of San Francisco, who joked, “I’ve heard of gay power, but this is ridiculous.”

Rainbow was also a San Diego rock group—not to be confused with the British band of the same name, founded in 1975—that performed at a pride parade in 1972 organized by the Christopher Street West group in Los Angeles. The group also played a gay-straight dance organized by the Gay Students Union of the University of California, Irvine. Given the existence of the Rainbow Valley and Rainbow settlement of San Diego, one might wonder whether the band’s name is simply a queer coincidence.

Coming out

Activist Arnie Kantrowitz’s 1977 autobiography, Under the Rainbow: Growing Up Gay is much more explicit in its use of symbolism. The title draws directly from the Garland song, comparing the highs and lows of life and gay politics to Dorothy’s journey to Oz. The author describes his experience at New York’s first gay pride march: “Arms linked, the legions of gays were marching to Oz. We were off to see the Wizard. We were coming out.” Kantrowitz’s work was widely reviewed in a number of periodicals, wherein fellow gay men faulted him for his “trivial, obvious metaphor” and “unfortunate title.”

Love poems

With each new interpretation, the rainbow was revealed to have universal and flexible connections to a variety of experiences—not just for queer people, but for all folks othered by society. With Ntozake Shange’s 1976 choreopoem (dynamic poem combining different types of artistic expression) “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf,” the colors of the rainbow are embodied by the characters themselves, exploring themes of sexuality and misogynoir (a term coined by queer black feminist Moya Bailey to describe misogyny directed at black women.) As the playwright and poet herself put it:

“The rainbow is a fabulous symbol for me. If you see only one color, it’s not beautiful. If you see them all, it is. A colored girl, by my definition, is a girl of many colors But she can only see her overall beauty if she can see all the colors of herself. To do that, she has to look deep inside her. And when she looks inside herself she will find . . . love and beauty.”

Ntozake Strange, “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf,” 1976

Solidarity forever

In the world of politics, the Rainbow People’s Party (formerly the White Panther Party) was a white allies offshoot of the Black Panther Party founded in 1968. Meanwhile, the Original Rainbow Coalition was a 1969 alliance formed between the Chicago Black Panthers (led by Fred Hampton), the Puerto Rican Young Lords, and the Young Patriots Organization to address issues of classism—a group later replicated by Jesse Jackson’s National Rainbow Coalition, founded in 1984. The mid-20th century was a time of vibrant social change and activism, with rainbows providing potent political symbolism for unity and diversity.

The future of the rainbow

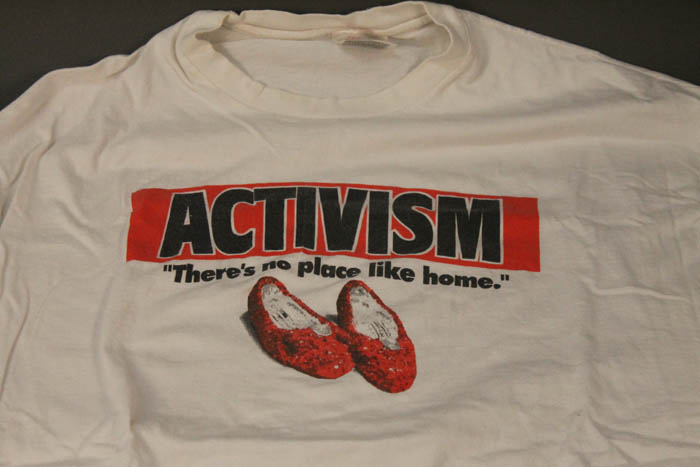

Today, the pride flag is ubiquitous. From parade floats to boutique swag, a confluence of commercial interests and respectability politics have rendered it the go-to logo of “the gay agenda,” along with hashtags and slogans that have helped frame watershed moments such as marriage equality and media representation in palatable and punchy terms. But what about the issues that persist, such as homelessness, discrimination, and access to health care? Where are the battle cries and banners under which we can rally for these causes? The rainbow is a flexible symbol, and we’re curious to find out how and where it will appear next. How will you draw on these histories of the rainbow to create your own?

GVGK Tang was a summer 2018 curatorial intern with Dr. Katherine Ott in the Division of Medicine and Science at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. This piece was originally published by the museum’s blog, O Say Can You See?

Posted: 6 June 2021

I believe the history lesson in this article is not accurate, perhaps by accident or deliberately.

Genesis 9:8-17 8Then God said to Noah and to his sons with him: 9″I now establish my covenant with you and with your descendants after you 10and with every living creature that was with you-the birds, the livestock and all the wild animals, all those that came out of the ark with you-every living creature on earth. 11I establish my covenant with you: Never again will all life be destroyed by the waters of a flood; never again will there be a flood to destroy the earth.” 12And God said, “This is the sign of the covenant I am making between me and you and every living creature with you, a covenant for all generations to come: 13I have set my rainbow in the clouds, and it will be the sign of the covenant between me and the earth. 14Whenever I bring clouds over the earth and the rainbow appears in the clouds, 15I will remember my covenant between me and you and all living creatures of every kind. Never again will the waters become a flood to destroy all life. 16Whenever the rainbow appears in the clouds, I will see it and remember the everlasting covenant between God and all living creatures of every kind on the earth.” 17So God said to Noah, “This is the sign of the covenant I have established between me and all life on the earth.”