Recognizing the best America has to offer

Once reserved for military heroes, the Congressional Gold Medal has been awarded to poets and baseball players, police officers and civil rights activists, in recognition that there is more than one way to be an American hero.

Since the first Congressional Gold Medal was awarded to George Washington in 1776, the distinguished honor has told the story of America by recognizing our heroes on the battlefield, sports legends, pioneers of science, and other luminaries.

On loan to the National Museum of American History from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

The award, which initially was bestowed on military leaders, has expanded to recipients across a wide range of fields, including the Wright brothers, poet Robert Frost, and baseball great Jackie Robinson. Some medals which have been awarded to groups were assigned by Congress to the Smithsonian collections for display and research, including medals honoring Japanese-American WWII soldiers, the African-American Tuskegee Airmen, Native American code talkers, and the Women Airforce Service Pilots. Surviving group members and their families are invited to a presentation ceremony and many receive a bronze replica of the gold medal.

At the National Museum of American History, Curator of Military History Jennifer Jones curated an exhibition in 2014 titled American Heroes: The Japanese American Nisei Congressional Gold Medal. The gold medal, which is included in the museum’s collection, honors more than 33,000 second-generation Japanese Americans, or “Nisei,” who served honorably during WWII even though many had families who were wrongfully imprisoned in concentration camps in the United States. The exhibition traveled across the country with the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service.

Copyright © 2002 Smithsonian National Museum of American History | Photograph by Jack Iwata, courtesy of the National Archives.

In 2016, the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center hosted an online exhibition developed by the National Veterans Network with the Smithsonian which told the life stories of 12 of the Nisei soldiers. The network was instrumental in securing the gold medal legislation. Jones is helping review classroom materials now about the soldiers’ accomplishments.

“The value of these Congressional Gold Medals is that we’re educating the next generation about the history and stories of those who served and the families who supported them,” she said. “There are values associated with the gold medals – heroism, sacrifice, selflessness and service. Those are all really important values no matter who you are.”

The Nisei soldiers served in segregated units and faced discrimination both at war and at home despite their heroism in battle and their vital contributions as Japanese translators. Their motto was “Go for Broke.”

“They were seen as fierce fighters and many of them were trying to show their loyalty to the United States, and they were going to fight for the rights of all those Japanese Americans who were incarcerated at home,” Jones said. “They were one of the most highly decorated units for their size and length of service, but they also were used as cannon fodder. They were sent in twice to rescue the same Texas regiment. They served under white commanders who sometimes viewed them as expendable.”

The medals sometimes seek to symbolically right past wrongs, or at least acknowledge the government’s complicity in discrimination, although that may occur decades later. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King were awarded medals in 2004, more than three decades after King’s assassination. Civil rights activists who marched in Selma in 1965 were awarded a medal on the 50th anniversary in 2015.

Jones and other curators in military history are working now with a new curator in Puerto Rico to collect stories and artifacts related to the 65th Infantry Regiment “Borinqueneers,” a segregated Army infantry regiment of Puerto Rican soldiers established in 1898 who served honorably in WWI, WWII, and the Korean War before being fully integrated into the Army. Legislation was passed and signed by President Barrack Obama in 2014 to award a gold medal honoring the regiment, and the medal was formally presented in Puerto Rico in 2016.

“These are underrepresented groups in the museum’s collections so having these medals gives us the opportunity to reach out to these communities that have not been represented in our exhibitions and collections to try to get those stories and artifacts,” Jones said.

As the highest honor bestowed by Congress, legislation to award a medal must be approved by the House and Senate. Once the bill is signed by the president, the process moves to the U.S. Mint, which includes consultation with the Citizens Coinage Advisory Commission and the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. The Secretary of the Treasury then approves the design of the medal which is engraved and struck by the U.S. Mint. The process often takes more than a year before the ceremonial presentation of the medal.

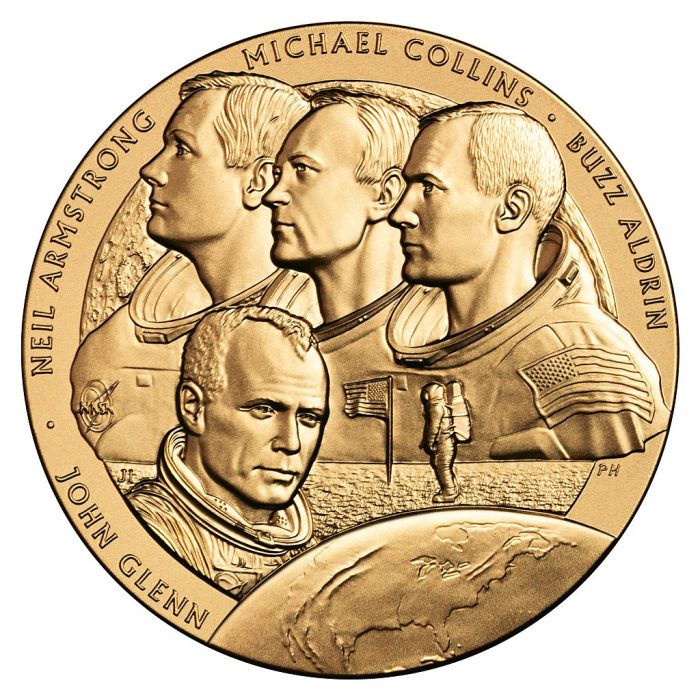

(US Mint design: Joel Iskowitz – US Mint catalog)

In recent legislation, the House approved a bill in March to award a Congressional Gold Medal to law enforcement officers who protected the Capitol during the riot and insurrection on Jan. 6. If the bill is approved, one medal would be awarded to the U.S. Capitol Police, one to the D.C. Metropolitan Police, and a third to the Smithsonian collection.

Other recent bills have been proposed for medals that would join the Smithsonian collection, including for the hostages in the Iran hostage crisis, civil rights-era Freedom Riders, and environmental justice activist Hazel M. Johnson.

Editor’s Note

Recently, the award of a Congressional Gold Medal became a cause of controversy as the House and Senate debated whether to honor Capitol Police officer Eugene Goodman a medal. Goodman confronted an angry mob of insurrectionists in the Capitol Jan. 6, 2021, and diverted them away from the Senate chamber.

Ultimately, the Senate voted to honor not only Officer Goodman but also other federal officers who helped repel the Trump-inspired mob and restore order in the world’s most important democratic capital. The House passed the Gold Medal legislation June 16, 406 to 21, with all opposing votes coming from conservative Republicans.

Read more:

Congressional Gold Medal vote passes House as 21 Republicans vote no

CNN.com – June 15, 2021

House, Senate strike deal to give Congressional Gold Medal to all officers who responded on Jan. 6, not just Goodman.

The Washington Post – June 15, 2021

Brendan L. Smith is a freelance journalist and communications consultant with 25 years of experience with newspapers, magazines and websites. He is a regular Torch contributor.

Posted: 15 June 2021