We wants to make your flesh creep

For some creepy Halloween fun, Rebecca Seel combed the collections of the American History Museum to uncover six common phobias—sort of a historical Fear Factor.

The dark (nyctophobia)

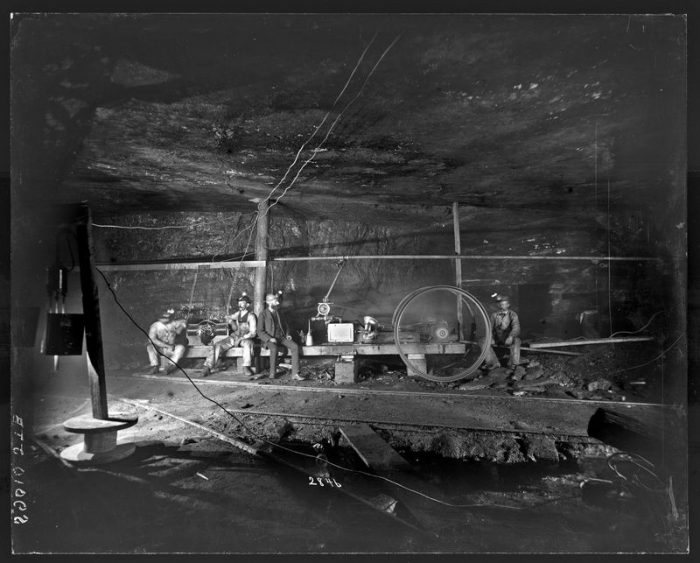

Perhaps most pervasive in childhood, fear of the dark can still spook us as adults! Miners in the past got used to working in the dark. They used many different sources of light to guide their way underground, but many of those methods came with dangerous trade-offs. Oil-wick and carbide lamps could be hung on the brim of a cap, letting miners work quickly and efficiently in the dark, but their open flames could (and often did) ignite flammable gases. Deadly explosions were tragically common in U.S. coal mines until the early 20th century. If you’d like to learn more, check out the museum’s expansive collection of mining lights and hats.

(Also, this 1897 mining journal may shed some light on the life of miners, including their harsh working conditions in the dark.)

Germs (germophobia or mysophobia)

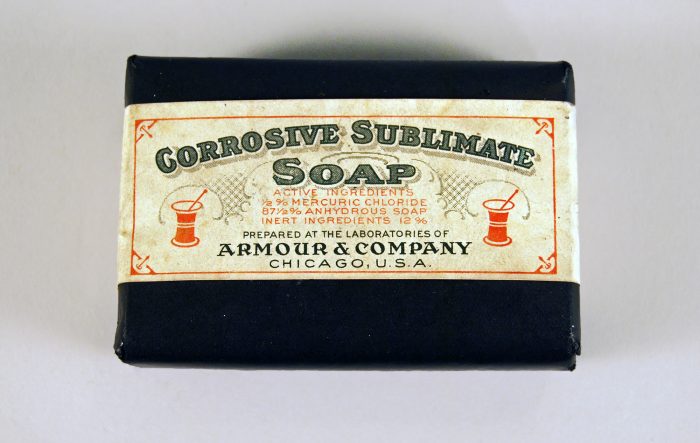

While we may have the comforts of antibacterial hand gel, surgical masks, and modern medicine, previous eras had different soaps and cleansers that a germ-averse person might have turned to for their ailments.

One ingredient in this Corrosive Sublimate Soap is mercuric chloride, which was used in early antibacterial soaps and is still used in skin-whitening soaps. Nothing to fear from mercuric chloride, except brain damage, kidney failure, and drooling.

Also, anyone concerned with germs may have found solace in Tarkon Germicide and Antiseptic, with the following varied and myriad uses provided by the manufacturer: “Acid Mouth, After Shaving, Catarrh, Bad Breath, Cold Sores, Dandruff, Ear Troubles, Eye Troubles, Hives, Insect Bites, Odors, Piles, Pyorrhea, Sunburn, Women’s Hygiene, Wounds, General Disinfecting and Deodorizing.”

Dogs (cynophobia)

People scared of canines may not hold warm feelings toward Stubby the dog, but this pup was a brave companion to American soldiers. “Sgt. Stubby” found himself in a scary situation or two, serving in 17 battles during World War I. Once, he even managed to capture himself a German soldier! Upon returning home from the war, Stubby received fame and accolades, including visits to the White House and a meeting with General John J. Pershing.

Stubby lived on to strike fear in the hearts of his opponents when he became the mascot for the Georgetown Hoyas.

Flying (aviophobia)

Imagine you have a fear of flying. Now imagine that it is the 1860s and you are an aerial spy floating in a hot-air balloon, trying to spy on the Confederates. Thaddeus Lowe, an aeronaut who conducted military reconnaissance in balloons, had no such fear, as he enthusiastically took to the sky in his balloon called the Intrepid, spying on Confederate camp and troop movements at the battle of Fair Oaks. While plenty of people may have balked at Lowe’s flying, President Lincoln was filled with wonderment and couldn’t stop talking about the amazing floating spy machine.

Mice (musophobia)

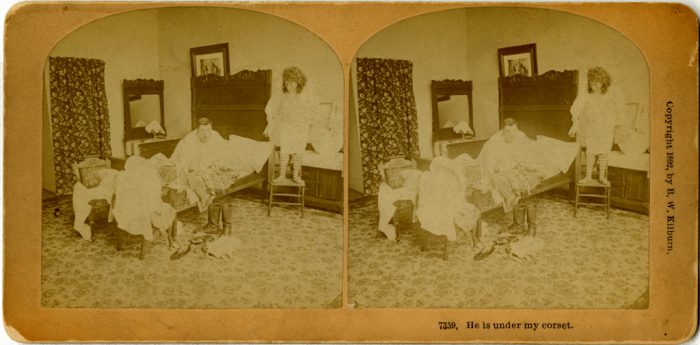

What is it about mice that makes one shriek? That causes one to jump on the nearest available flat surface, as this 1892 stereograph depicts?

Scientists who are afraid of mice must rise above it. The OncoMouse is a genetically modified laboratory mouse created in the mid-1980s to carry a specific gene that aids scientists in cancer research. Mallory Warner of the Division of Medicine and Science discusses the patented creature and the ethical concerns it raises surrounding animal research.

Thunder/Lightning (astraphobia)

Thunder and lightning aren’t so frightening. Well not to Ben Franklin, that is! While bolts of lightning snaking across the sky may frighten many of us, Franklin stayed outside to perform his famous kite experiment in which he attempted to prove that lightning was an electrical force. This painted panel dates to the early 19th century, when it was popular for volunteer fire companies to proudly decorate their engines for use in parades. The panel depicts the famous scene in 1752 as Franklin and his son William (actually 21 years old at the time!) stand in the storm to observe the experiment.

Last, but certainly not least, the Torch would like to contribute the creepiest phobia of them all: Pediophobia, a fear of dolls:

Boo!

Rebecca Seel works in the New Media and Communications and Marketing offices of the American History Museum. She is terrified of spiders. This post was originally published in 2018 by American history’s blog, O Say Can You See?

Posted: 29 October 2021

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture