Why Museums Are Primed to Address Racism and Inequality in the U.S.

Smithsonian leaders discuss how the Institution can be a powerful place for investigating and addressing society’s most difficult issues

Why would Filipino Americans, who make up 4 percent of the nation’s nursing corps, represent 30 percent of Covid-19 deaths among nurses in the United States?

Why do Latinas in major fields of employment have to work 22 months to equal the pay of what white men received over a 12-month period?

Why would a mistaken drug raid lead law enforcement agents to fire ten rounds blindly into the home of health care worker Breonna Taylor, killing her?

Why do Asian Americans have a sense of historical déjà vu in the wake of new violence against them?

Questions like these represent just a few of the uncomfortable realities that have emerged from a cancer in the American mind—racism in its many forms. Like a disease that continues to spread and endanger the nation’s well-being, racism has scarred American life since Europeans set foot on American soil centuries ago. The Smithsonian’s new initiative, “Our Shared Future: Reckoning with Our Racial Past,” seeks to expand understanding of how racism has blighted today’s world and threatens to poison the future if Americans do not confront the danger and open their minds to give all Americans equal rights, equal opportunities and equal access to the American dream.

Six Smithsonian leaders joined together last week for “From ‘Our Divided Nation’ to ‘Our Shared Future,’” a discussion about how the Smithsonian plans to tackle racism within its museums and research centers. Kevin Gover, Smithsonian undersecretary for museums and culture, raised questions for Anthea M Hartig, director of the National Museum of American History; Kevin Young, director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture; Deborah L. Mack, director of the “Our Shared Future” Initiative; Theodore S. Gonzalves, interim director of the Asian Pacific American Center; and Tey Marianna Nunn, director of the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative. Also participating was Alan Curtis, president of the Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation.

“It is time, I suggest, to seize the day, renegotiate the social contract and change the rules of the game,” Curtis says. “The goal is not to get back to normal. Normal has been the problem in America.” Ironically, the impetus for attacking racism’s corrosive role today springs in part from a long-overlooked 1968 report.

More than 50 years ago, the Kerner Commission report, an analysis of 1967 racial disturbances, determined that the cause of disruption in urban Black neighborhoods was not outside agitators or media attention as some politicians claimed. Instead, the cause was, very simply, white racism. “White Society is deeply implicated in the ghetto,” the report declared. “White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.” Correcting the problem, it said, “will require new attitudes, new understanding, and above all, new will.” The report concluded that without dramatic change, “our nation is moving toward two societies, one black and one white—separate and unequal.” Furthermore, it addressed a frequent cause of racial conflict in American life today—the continuing impact of police violence in triggering racial clashes. “The abrasive relationship between the police and the minority communities has been a major—and explosive—source of grievance, tension, and disorder.”

The report argued that “it is time now to turn with all the purpose at our command to the major unfinished business of this nation. It is time to adopt strategies for action that will produce quick and visible progress. It is time to make good the promises of American democracy to all citizens—urban and rural, white and black, Spanish surname, American Indian, and every minority group.”

Unfortunately, no one seemed to be listening. President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had ordered the report, quickly buried it. The report’s findings generated little organized attention in 1968, and many of the same problems plague African American life today, according to a 2017 report. Poverty, segregation and unemployment remain higher within Black neighborhoods, while access to health care is lower. Less than half as many African American people attend white-majority schools now when compared with the 1980s, the analysis found, and the rate of African American incarceration has tripled since 1968.

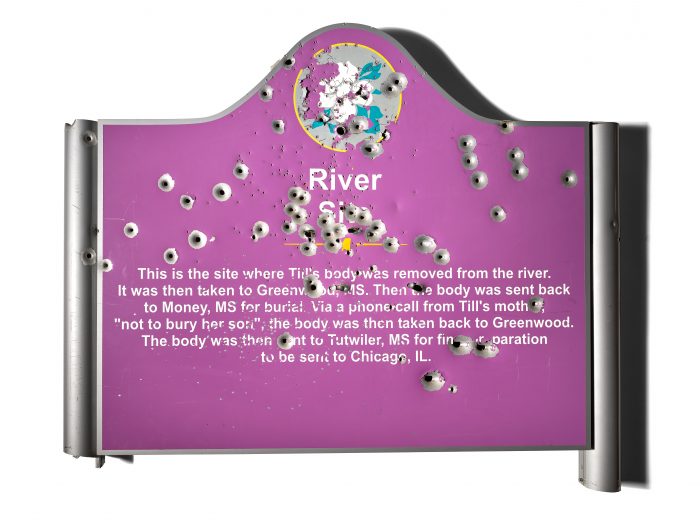

Early steps in the Smithsonian’s commitment have included a national virtual dialogue, “Our Shared Future: Reckoning With Our Racial Past Forum” on August 26; the display of a vandalized sign at the National Museum of American History that marked the location where Emmett Till’s body was pulled from the river after his brutal murder in 1955; and a new book and exhibition, both titled “Make Good the Promises: Reconstruction and Its Legacies,” at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC).

The exhibition showcases remnants of the post-Civil War Reconstruction era and its failed promises. Reconstruction pledged to offer new rights for African American people, but at the same time, it spurred white violence that sparked retrenchment and a failure to safeguard for Black Americans the right to vote and the opportunity for economic equality. In much the same way, the push for equal rights in the 1960s and 1970s drove a shift into reverse during the 1980s. And again, while Americans elected their first Black president in 2008, recent years have seen the growth of white supremacist groups and increasing evidence of violence by white police officers against Black Americans.

Another new exhibition at NMAAHC, “Reckoning: Protest. Defiance. Resilience,” tells the story of the African American fight for constitutional rights, including the Black Lives Matter campaign. Among its focal points is a portrait of Breonna Taylor, a Louisville health care worker slain by police gunfire in her own home.

On loan from Amy Sherald, © Amy Sherald

Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch, who has urged the institution to fulfill its highest ideals, believes museums can take a special part in helping people view their own histories and those of others in a way that will make it possible to create a future that is knitted together, recognizing commonalities and forging alliances rather than encouraging racial divisiveness. “Museums ask audiences to enter a common space and explore a common interest,” he says. Inevitably, as a 175-year-old institution, the Smithsonian often has reflected the racial attitudes of those who led it and of the dominant culture outside the museums’ doors. The “Our Shared Future” initiative, Bunch says, “will explore history and legacy of race and racism through interdisciplinary scholarship, dialogue, engagement and creative partnerships.”

The Smithsonian plans to reach out to other museums—large and small—in this initiative. Gover points out that there are more museums in the United States than there are McDonalds and Starbucks put together. A recent report by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, supported by Reinvestment Fund, found “the presence and usage of public libraries and museums to be positively associated with multiple dimensions of social well-being—in particular community health, school effectiveness, institutional connection, and cultural opportunity.”

“This is about really welcoming people to engage with who they fully are. . . . I also believe it’s an obligation, given that the American people are the ones who fund much of what we do.”

Deborah L. Mack

Young believes museums should help people see “that this is a precedented time” and that the friction that exists today between races is not new. He thinks it is vital “to help contextualize the moments we’re in and have deep conversations about those moments.” He also is convinced that museums can change the world, but he contends that they are not working alone in taking on that task. “What we’ve seen is an outpouring of people caretaking Harriet Tubman’s handkerchief, shawl and veil for generations. The [1968] Poor People’s Campaign wall, people had kept it and held onto it [before it reached the museum]. So it’s not just believing in the museum, but believing in the people who believe in the museum. And to me that’s crucial to the future and to all of us.”

Gonzalves sees current racial attacks on Asian Americans as a story of “shock and misery and woe,” but like Young, he points out that this is not a new phenomenon. “These are very old stories, and when we talk about this season, the season of hatred and violence in which Asian faces are now targets again, we have come to this moment where we understand that this is a place that we have been before,” he says. “What we’re trying to convey, whether it’s African American, Native stories, Chicano Latino stories, Asian Pacific Islander stories, it’s about how. . . . all of us have been here before. So our responses might be different, but some of our responses are the same.” Moreover, he asserts that “we are more than what has been done to us. We have to be more than the victimization of our history.”

In looking forward, Curtis declares that “we need to motivate believers in Kerner and healing priorities to continue the struggle. But we also need to communicate to independents and fence-sitters, as well as to Americans who may be opposed to Kerner and healing priorities like at least some white [people] living in poverty, and like state legislators who have passed voter suppression laws.”

Hartig looks to the future hopefully. “I think that it’s possible for us to create a very complicated landscape of interwoven narratives in which we see the intersections. . . where we understand the solidarities, where we know and come together to make change, where we’ve created opportunities for each other.” She sees coupling the powers of historical interpretation with community justice tools. “We’re launching the Center for Restorative History, which aims to combine the methodologies of restorative justice with those of public history. Doing what we know how to do—collect and interpret—and address the harm that we’ve done as the Smithsonian, as well as the good that we can do moving forward to help heal the nation.” Nunn adds to that thought, saying, “We have to look backward, go fix that, so we can move forward with it fixed.”

This multi-year project is unique because of its “completely pan-Smithsonian approach,” says Mack. It involves all of the institution’s museums and research centers. “This is about really welcoming people to engage with who they fully are. . . . I also believe it’s an obligation, given that the American people are the ones who fund much of what we do.”

Nunn agrees. “Those are things that, really, museums, libraries and cultural institutions, whether virtually or physically in a space, have a social responsibility to investigate, and address” and invite dialogue. “Museums are considered trusted members of community, and we need to facilitate all these dialogues.”

The work to transform an institution is challenging, says Mack. “It’s been great to bring on the next two generations of practitioners, of staff, across [the] Smithsonian, to see them engage in this work in ways that actually reinforces their activism, their sense of equity, their sense of social justice, and in a sense that also tells them that when they come to Smithsonian, they can bring their total selves.”

Young believes that people visit museums day after day to learn about themselves as well as their history. Beyond that, he says, “I also think there’s a real opportunity in the museum to think about how we can collect what’s happening now, and the newness, collecting the now and the new is something I’ve been saying. And thinking about history as living, and indeed, living history has also come to the fore as something we’ve been talking about a lot at the museum. Because we are living through history. History is living in us.”

Watch the discussion

Alice George, Ph.D. is an independent historian with a special interest in America during the 1960s. A veteran newspaper editor, she is recently the author of The Last American Hero: The Remarkable Life of John Glenn and has authored or co-authored seven other books, focusing on 20th-century American history or Philadelphia history.

This post was originally published Nov. 4, 2021 by Smithsonian magazine. Copyright 2021 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

Posted: 8 November 2021