An Impact Beyond Film

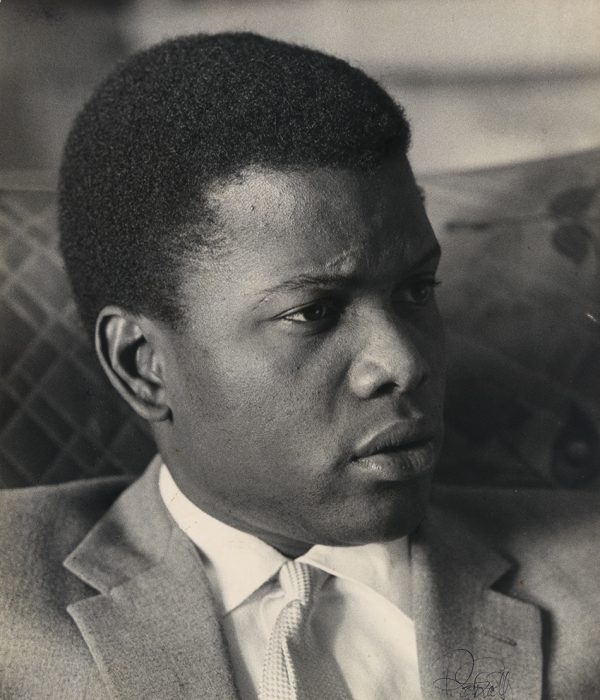

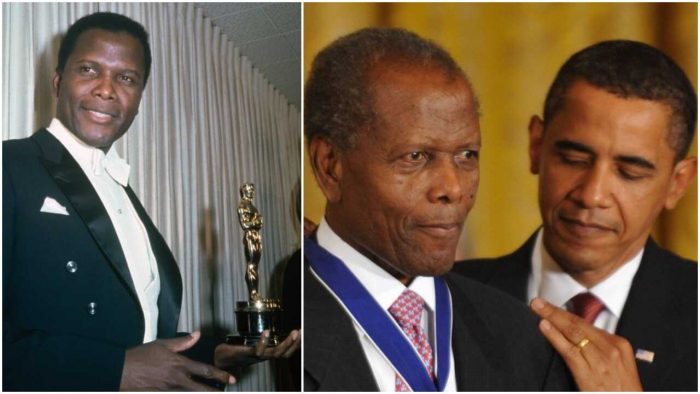

Secretary Lonnie Bunch remembers actor and film director Sidney Poitier, who became the first African American to win an Academy Award for Best Actor and who left a lasting legacy of dignity and respect.

Born in Miami, Florida, in 1927, Poitier moved to New York City at sixteen to start his theatre career. He briefly returned to the stage in 1961 when he performed on Broadway in Lorraine Hansberry’s Raisin in the Sun. Impatient with the stereotypical roles assigned to Black actors, Poitier wrote the story, For Love of Ivy, which became the first mainstream romantic comedy to feature two African American stars. Poitier explained: “I look back on those people who came before me, and I owe them a debt…I knew when I came on the scene how painful it had to have been for them sometimes.”

Off-screen, Poitier was an activist in support of the Civil Rights movement. In 2009, Poitier was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

The recent death of Sidney Poitier has generated an almost overwhelming array of tributes, ranging from the personal memories of luminaries such as Harry Belafonte, Barack Obama, Oprah Winfrey and Viola Davis to thousands of anonymous fans on social media that rightly focus on Poitier’s talents as a pioneering performer and director, his impact on redefining the image of the black actor in film and his influence on generations of African Americans who followed him in Hollywood. There is little doubt that Poitier’s talents and tenacity, along with that of other actors such as Ivan Dixon, Dorothy Dandridge and James Edwards, helped to transform an industry that saw black actors as comic relief or as stereotypical figures that assured white audiences that there was little to fear from an evolving and politically vocal black community. Poitier deserves all the acclaim that Hollywood can generate. Yet, to many black men, including myself, who are baby boomers who came of age during the 1960s and early 1970s, Sidney Poitier’s impact went well beyond the film industry: his presence, his demeanor, his dignity, helped a generation of black men find a sense of identity, place and possibility as well as helping us grapple with the contradictions and limits of racial change.

I first learned of Sidney Poitier in 1964 when my father insisted that I accompany him to see the film, Lilies of the Field, because Poitier has just earned the Oscar for Best Actor–a first for a black actor that was more important to my father at the time than to me. All I remembered from the film was a joyous scene where Poitier taught a group of nuns to sing a black spiritual, “Amen,” which I thought reinforced stereotypes about the musical affinities of blacks and had little meaning for someone on the verge of manhood. Yet from that less than inspiring first encounter, I found myself drawn to Poitier’s films over the next decade, as my father and I found common ground over our shared love of movies and my growing interest in the challenges and possibilities of being black in a changing America. And change was swirling all around my generation–from a freedom movement that culminated in Civil Rights legislation to a redefinition of blackness through music, theatre, literature and film. Helping to guide many of us through this exciting but uncertain era were the films of Sidney Poitier.

I discovered and drew inspiration from his early films such as No Way Out (1950), where Poitier played a young doctor who had to confront racism as the first black doctor in an urban hospital. He provides medical care to white patients who refuse his aid and later in the film, saves the life of a man who threatened Poitier because he believed that his brother’s death was due to a “colored doctor.” In Edge of the City (1957), Poitier portrays a dock worker who fights to protect a white friend from bullying. Though Poitier’s character is killed in the struggle, the film highlighted both the need to combat racism and the then unusual interracial friendship. Both films had an important impact on me. No Way Out provided a glimpse of the possibilities that African Americans might encounter in a changing world, while Edge of the City taught me that the struggle for fairness is not without sacrifice. The death of Poitier’s character reminded me of a line penned by Claude McKay, “…pressed to the wall dying, but fighting back.” These two films spoke volumes about the possibilities of blackness–That there was a new era of possibilities and hope for me to aspire to things that once seemed unreachable, but also that it is necessary to be willing to fight discrimination wherever it exists. Even if one loses the immediate battle, that loss would inspire others to continue to fight the good fight. These films helped so many of us dream a world anew.

But the film that offered the most hope for racial change and had the greatest personal impact on me was In the Heat of the Night. This 1967 film paired Poitier with Rod Steiger as a southern police chief who represented the racial attitudes exemplified by men like Bull Connors who turned hoses and dogs on the civil rights activists in Birmingham, Alabama. In this film, Poitier portrays a homicide detective from Philadelphia who clashes with Steiger, who cannot accept that a black man has achieved such respect in his profession. Ultimately, the two work together to find a murderer. One famous scene is what we often called “the slap heard round the world.” When Poitier confronts one of the town’s elite landowners, the conversation escalates and the white man strikes Poitier, who instantly slaps him back, to the horror of the police chief and the astonishment of the landowner’s black servant (played by Jester Hairston.) To many black men of my generation, Poitier’s slap symbolized a new day when blacks would no longer tolerate the racist actions and violence that so often affected black communities. Like many, I cheered Poitier’s reaction. But the scene that most vividly symbolized a new day to me is the famous interaction when Steiger’s Chief Gillespie, after Poitier’s Virgil Tibbs resents being called “boy,” sneeringly asks, “What do the call you in Philadelphia?” The moment that Poitier responds, “They call me Mr. Tibbs” brought home that we could and must demand respect. We would no longer accept the denigration of being referred to as “boy” or allow our elders to be called “Uncle” rather than sir or mister.

As I neared college, I relied less on the inspiration from Poitier’s films. While my struggles to find my place and my identity were enriched by my time at Howard University, where I was introduced to many authors from James Baldwin, to Claude Brown to Maya Angelou to Franz Fanon, I never forgot that Sidney Poitier was instrumental to a young boy’s journey to find his identity and to believe a new world of possibilities existed. So I mourn the film legend but I revel in the career of a man who symbolized an evolving black identity that demonstrated that racial change was not only possible but inevitable.

Posted: 13 January 2022

-

Categories:

Art and Design , Feature Stories , History and Culture , Portrait Gallery