How a Smithsonian Botanist Cracked the Cactus Code a Century Ago

Celebrate National Cactus Day by meeting the pioneering botanist, Joseph Nelson Rose.

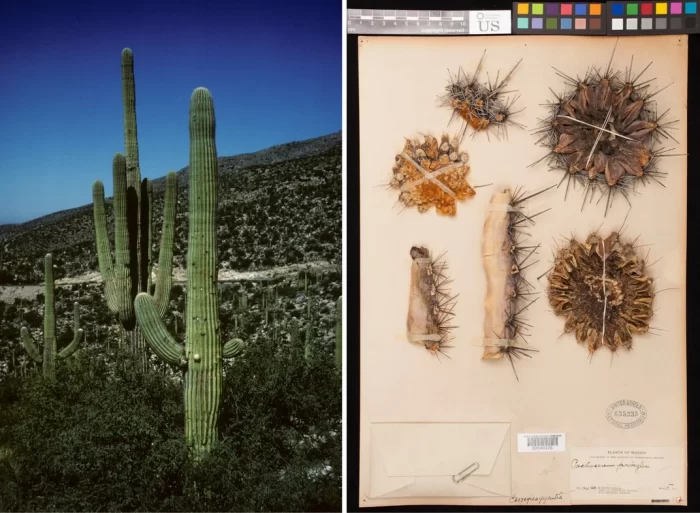

Many of us think of cacti simply as bristly, parched plants that live in the desert. But this simple definition undersells their remarkable diversity. Cacti are found from the edge of the Canadian tundra to the tip of South America. They come in all shapes and sizes, from ground-bound cushion-like plants to barrel-shaped giants that soar some fifty feet into the air.

While many are adapted to survive in harsh deserts, some cacti reside in wet tropical environments. Wherever they are, cacti are vital cogs in their ecosystems. Their bright flowers and fruit provide food for everything from insects and bats to iguanas and humans and larger cactuses provide safe haven for nesting birds.

Considering this staggering diversity and ecological importance, it’s no wonder why the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History has assembled a treasure trove of cacti specimens. But the museum’s collection contains much more than just barbed bits of dried cacti. The Botany Department also oversees a collection of historic photographs, notes and colorful cactus watercolors. “It’s among the most important collections in the world,” says Kenneth Wurdack, one of the museum’s research botanists and associate curator of botany.

Many of these specimens and documents relate to Joseph Nelson Rose, the pioneering botanist who literally wrote the book on cacti. “If you care about the history of botany and the history of collections, then you know that Rose is one of the most important collectors and foundational people for the National Herbarium,” Wurdack says.

To celebrate National Cactus Day, learn more about how Rose and the museum’s cactus collection transformed our understanding of these prickly plants more than a century ago.

Rose and his thorns

Joseph Nelson Rose was born in Indiana in 1862. The son of a Civil War casualty, Rose was fascinated by the flowers sprouting up around his family’s farm from a young age. After securing a botany degree, Rose moved to Washington in 1888 to work with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), which managed the sprawling collection of dried plant specimens in the National Herbarium. When the Smithsonian acquired the collection in 1896, Rose came along with it.

As he organized the herbarium specimens in the National Museum, Rose began corresponding with several botanists on one of the era’s most puzzling botanical topics: the prickly taxonomy of cacti. Back then, few scientists had a grip on how the spiny plants related to one another. They often lumped disparate cactus species from across the Americas into bloated groups, or genera, overstuffed with strange cacti.

To tackle this thorny taxonomy, Rose teamed up with the eminent botanist Nathaniel Lord Britton. In the 1890s, Britton co-founded the New York Botanical Garden and became close with several wealthy industrialists, often naming new species of plants after them to help curry favor. One of these was Andrew Carnegie, who would help fund Rose and Britton’s endeavor to transform the world’s understanding of cacti.

In 1912, Rose left his associate curator position at the Smithsonian to pursue the project full-time. Over the next eleven years, he went searching for cacti around the world. He visited museums and botanical gardens throughout Europe, and collected cacti everywhere from Caribbean islands to the Andes Mountains.

Much of his collecting took place in remote areas of Mexico, which is home to the world’s greatest diversity of cacti. There, the scorching climate made field work grueling. But even as he labored to harvest thorny specimens under the desert sun, Rose maintained his keen eye for botanical observation and took copious notes.

He sent both preserved specimens and living plants back to Britton in New York City and to Washington, where many grew for years in greenhouses under Rose’s watchful eye. Altogether, Rose and Britton amassed more than 7,000 herbarium specimens.

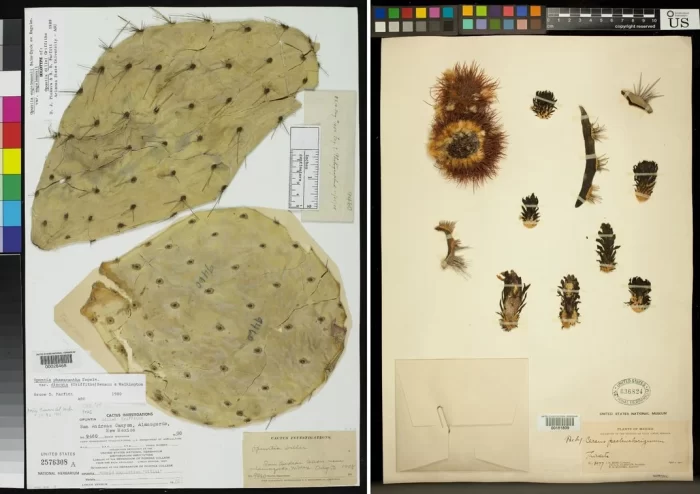

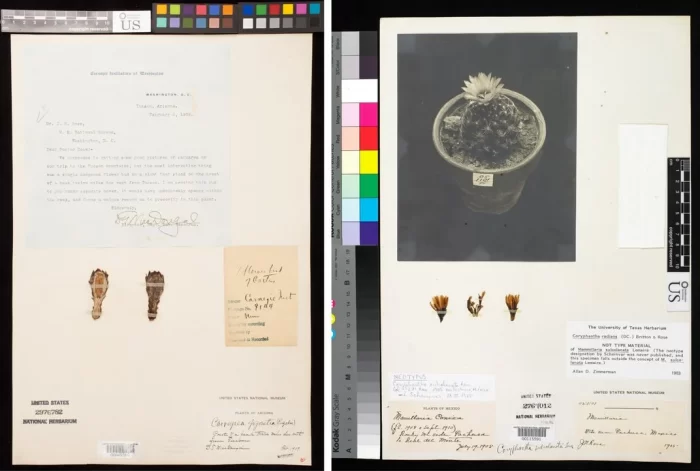

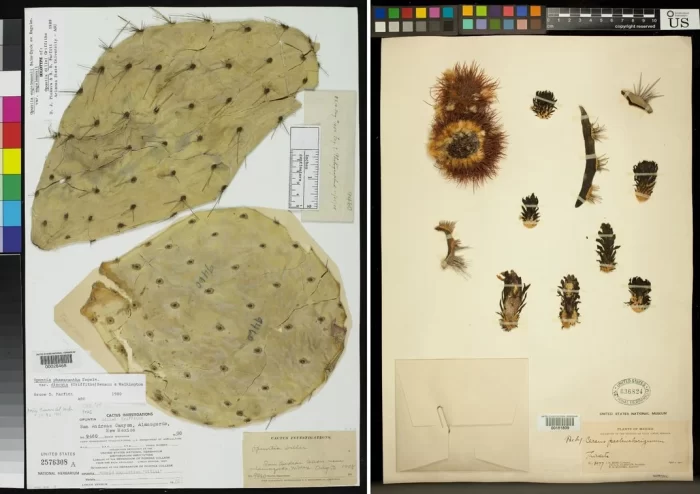

How to preserve a cactus

Most of the specimens in the museum’s herbarium are dried plants mounted onto sheets of paper, a style of preservation that dates back more than 500 years. But cacti complicate this age-old method with their spines and bulk. “You have to cut them up with a knife, and you put these little parts and pieces on the piece of paper,” Wurdack says. Then they’re sewn onto the paper with wire or string to insure the bits of cactus stay in place.

While the dried cacti husks pale in comparison to the aesthetic of a pressed leaf or flower, these specimens still sport some appeal. Occasionally, snippets of Rose’s correspondences and historical photos are pasted alongside the bits of cacti, giving the herbarium sheets the feel of a botanist’s scrapbook.

Reseeding the cacti family

As Rose continued to collect cactuses across Central and South America, he and Britton realized just how great the diversity of cacti really was. They completely overhauled cactus classification, increasing the number of known cacti genera fivefold and christening hundreds of new species.

One of their major changes involved renaming the towering, multi-armed saguaro cacti that dominate the Southwest. Due to its impressive size and distinct biology, they moved the bristled giant into its own genus, Carnegiea, naming it after the steel baron funding their work.

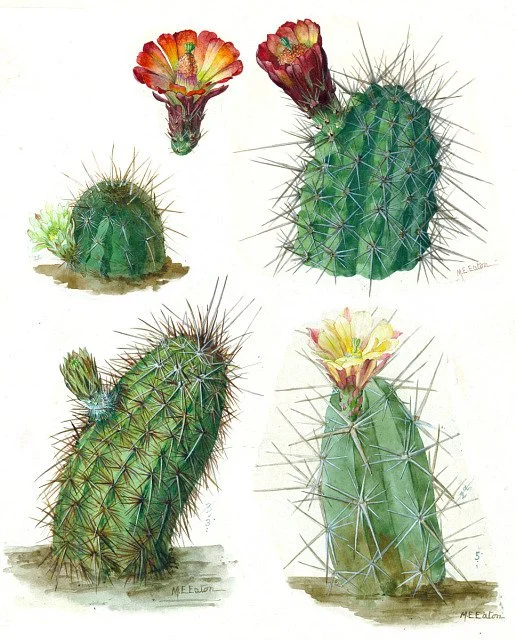

By 1923, Britton and Rose had published all four volumes of their groundbreaking treatise, The Cactaceae. Accompanying their detailed descriptions were lifelike watercolors by British artist Mary Emily Eaton that brought the beauty of these hardy plants to life. You can see a few of her paintings, alongside a squat barrel cactus (Ferocactus viridescens) specimen collected by Rose, in the museum’s Objects of Wonder Exhibit.

The Cactaceae was a hit throughout the botanical world. In a 1922 letter to a colleague, Rose wrote: “Interest in the cactus family has been greatly stimulated by the publication of these volumes. In Europe the interest is so pronounced that it may almost be called a cactus craze and dealers and cactus fanciers are anxious to obtain seeds and plants.” Through their intensive collecting and research, Rose and Britton had made the often overlooked cactus a botanical big shot.

After more than a decade focusing solely on cacti, Rose returned to his position at the Smithsonian in 1923. Widely lauded as a mild-mannered and cooperative researcher, Rose continued to produce botanical studies at an impressive clip, authoring some 200 books and papers over his illustrious career. And he conducted his research to the very end. The day before he died at the age of 66 on May 4, 1928, Rose was examining plants in his lab at the Smithsonian.

A lasting botanical legacy

While the “cactus craze” Rose and Britton inspired eventually dissipated somewhat (however cacti remain popular to horticulturalists), their scholarly masterpiece held up remarkably well for decades. “They brought new order to the cacti that was revolutionary at the time,” Wurdack says. “For the better part of a century people relied on that big multivolume book.”

It was only with the advent of cutting-edge molecular research — methods that were unfathomable in Rose and Britton’s day — that some of their taxonomic theories became outdated.

Rose was also ahead of his time when it came to realizing charismatic flora like cacti needed to be protected from habitat loss and poaching. Shortly before his death, he campaigned to the National Park Service and the Department of the Interior to set aside a public park “with regard to the preservation of the cacti of southern California.”

Now cacti are under siege from a threat Rose did not envision. Although cacti are adapted to survive in some of the warmest and driest environments on Earth, recent research estimates that a warming climate could threaten sixty percent of all cacti species with extinction in the next few decades.

Even though Rose was not thinking about climate change when he was collecting cacti, the specimens he preserved and meticulously labeled a century ago offer invaluable clues for modern botanists to map changes in cacti distribution. The cacti preserved in the museum’s herbarium act like a botanical time capsule, offering a glimpse of where different cacti lived during cooler conditions.

The vast array of non-cacti specimens Rose collected and cultivated also retain their scientific value. “His legacy lives on in thousands of specimens held in the Smithsonian collections,” says Wurdack, who has used genetic information from some of Rose’s non-cacti specimens in his own research. “The DNA is still workable over 100 years later.”

Jack Tamisiea is a Science Communications Assistant at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. In addition to covering all things natural history for the museum’s blog, Smithsonian Voices, he tracks media coverage and coordinates filming activities for the museum’s Office of Communications and Public Affairs. Jack is currently completing his masters in science writing at Johns Hopkins University. In his free time, he loves exploring the outdoors with a notebook and camera. You can read more of Jack’s work at https://jacktamisiea.com.

This post was originally published by the Smithsonian magazine blog, Smithsonian Voices. Copyright 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

Posted: 10 May 2022

-

Categories:

Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories , Natural History Museum , Science and Nature