A bird in the hand

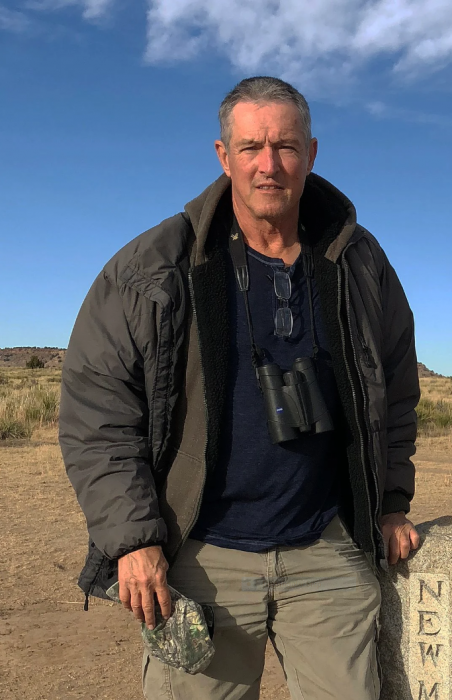

How Smithsonian Zoologist Gary Graves discovered his next research project in his own backyard.

Each day of the summer of 2020 and 2021, Smithsonian research zoologist Gary Graves went out to his backyard in the Ozark Mountains to face a familiar crime scene: the vibrant orange blooms of his trumpet creeper vine littering the ground, the flowers full of holes and torn to shreds. The perpetrator: a little flock of chestnut and yellow orchard orioles. Graves, a curator in the museum’s division of birds who specializes in birds like vultures and the microscopic organisms that live inside them, documented the magnitude of daily vandalism like a forensic analysis.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History shut down and few museum personnel were allowed entry. At the time, Graves was in the middle of a project studying the microbiomes of vultures, but the pandemic put that project on hold. Unable to conduct his regular research at the museum, Graves journeyed to his vacation home in the Ozarks to telework, about a thousand miles west of DC.

During the summer months, he noticed a persistent pattern of birds stealing nectar from his backyard flowers. He quickly recognized this behavior as unusual and unstudied and decided his next research project would be to characterize this behavior happening right in his own backyard.

“I was prohibited by the museum from doing any research travel and couldn’t get permission to do field research, so I was stuck in my yard,” said Graves. “But then I thought, ‘here is something that I can do.’”

What makes nectar-robbery particularly unusual? After all, nectar’s entire purpose is to be consumed by animals. However, not all nectar sips are created equal. Graves describes three different types of nectar consumption: legitimate pollination, nectar thievery, and nectar-robbery.

The first follows the common story of pollination – an animal coevolves with a flowering plant in a way that results in a mutually beneficial scenario. The animal, such as a bee or hummingbird, pollinates the flower and receives nutritious nectar from the plant as a reward.

“And that’s a nice clean story,” Graves said. “But in every system, there are always free-riders and cheaters.”

Those free-riders and cheaters are the nectar thieves and robbers. Nectar thieves are those who take the nectar without pollinating the flower but cause no harm otherwise. Flower anatomy typically fits their coevolved pollinator like lock and key, helping the pollinators live up to their namesake while enjoying their sweet nectar treat. Nectar thieves bypass this pollination system, taking the reward without fulfilling their end of the bargain.

“And that’s a nice clean story,” Graves said. “But in every system, there are always free-riders and cheaters.”

Those free-riders and cheaters are the nectar thieves and robbers. Nectar thieves are those who take the nectar without pollinating the flower but cause no harm otherwise. Flower anatomy typically fits their coevolved pollinator like lock and key, helping the pollinators live up to their namesake while enjoying their sweet nectar treat. Nectar thieves bypass this pollination system, taking the reward without fulfilling their end of the bargain.

According to Graves, avian nectar-robbery is not as well-known in North America as on other continents. The trumpet creeper observations have some neat implications in the broader field of pollination biology. So Graves took the opportunity to document it himself while in lockdown.

Every morning, Graves went out to assess the damage: how many flowers did these birds ruin? What method of destruction were they using? Did their methods change? He noted everything on a spreadsheet and did this for more than 40 days in both 2020 and 2021. Now, his paper describing the method of the mayhem appears in the journal Scientific Reports.

The main finding Graves described was that the orioles wrought havoc on the plant’s reproduction during their presence. The birds bored holes and robbed nectar from over 90 percent of the plant’s flowers, and the plant bore no fruit until the orioles departed the region on their fall migration. Extending the flowering season past the birds’ departure date may be the only way for this population of trumpet creepers to reproduce.

Results aside, Graves feels that the paper’s main take-home message is that the opportunity for scientific discovery is everywhere. There is no need to travel great distances or have fancy equipment to make noteworthy scientific discoveries – the next discovery could be hiding in plain sight in your backyard. But like all good detectives, scientists must have an inquisitive eye.

Megan Kalomiris is an intern in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Office of Communications and Public Affairs. She has previously written for the NIH Catalyst and Stanford News Service, among other outlets. Megan recently graduated from the University of California, Santa Cruz with a master’s in science communication. She also holds a BS in Biology from California State University, Fresno. You can read more of her work at https://megan-kalomiris.com/.

This article was originally published by the Smithsonian magazine blog, Smithsonian Voices.Copyright 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

Posted: 22 August 2022

-

Categories:

Feature Stories , Natural History Museum , Science and Nature