Elizabeth II Was an Enduring Emblem of the Waning British Empire

The British queen died on Thursday at age 96. Smithsonian magazine takes us on a journey exploring her long service to the Empire.

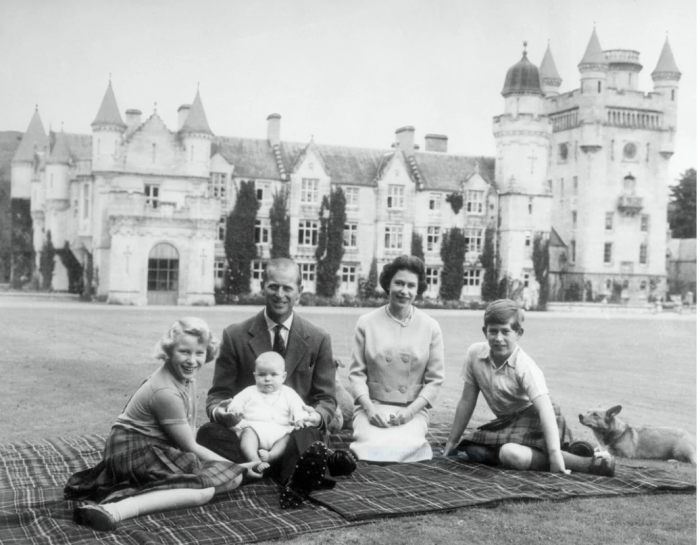

Elizabeth II, the long-reigning British queen who buoyed a shrinking empire and an increasingly embattled monarchy, died on Thursday at Balmoral Castle, her estate in the Scottish Highlands, at age 96. The royal family confirmed her death in a statement, saying, “The queen died peacefully at Balmoral this afternoon. The king and the queen consort will remain at Balmoral this evening and will return to London tomorrow.”

Elizabeth succeeded her father, George VI, upon his death in 1952, when she was just 25 years old. Over her 70-year reign—the longest of any British monarch and any female monarch in history—she worked with 15 prime ministers (16 counting Liz Truss, who took office earlier this week), met 13 of the past 14 American presidents, oversaw thousands of royal engagements and made 89 state visits overseas.

The queen’s steady presence symbolized stability during a period of profound change. Under Elizabeth’s leadership, the United Kingdom navigated multiple wars, ongoing unrest in Northern Ireland, leaps in technology, economic crises, Brexit, the rise of far-right nationalist politics, pandemics and the dissolution of a once-dominant empire. Four out of five people currently living in the U.K. were born after the queen’s ascension, making Elizabeth the only monarch most of her subjects have ever known.

Per the New York Times, her death “marks both the loss of a revered monarch … and the end of a figure who served as a living link to the glories of World War II Britain, presided over its fitful adjustment to a post-colonial, post-imperial era and saw it through its bitter divorce from the European Union.”

Inside Elizabeth II’s reign

Elizabeth was a private person who spent much of her life squarely in the public’s gaze. Her June 2, 1953, coronation ceremony aired live to 20 million television viewers—a royal first. Her meticulously planned funeral celebrations will likewise be televised, Tweeted, Tik-Toked and shared by millions on social media in the weeks to come.

Born Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor on April 21, 1926, the future queen became the U.K.’s heir presumptive at age 10, when her uncle, Edward VIII, abdicated the throne to marry American socialite Wallis Simpson. Conflict defined Elizabeth’s teenage years, with World War II breaking out in September 1939. At the behest of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the princess delivered her first public speech over the radio the following year. Speaking in carefully enunciated tones, 14-year-old Elizabeth—or “Lillibet,” as she was known to her family—stood next to her younger sister, Margaret, and delivered a message of comfort to Britain’s children, many of whom had been sent away from their families during the Blitz.

Toward the end of the war, in March 1945, the 19-year-old Elizabeth joined the British Army’s Auxiliary Territorial Service. She spent her days at a training facility, learning how to maintain vehicles, and her nights sleeping at nearby Windsor Castle. Her future husband, Prince Philip, served in the Royal Navy; the second cousins, who’d first met in 1934, exchanged letters throughout the war.

Against the advice of royal advisers, Philip and Elizabeth fell in love. They wed in November 1947 and remained together until Philip’s death at age 99 in April 2021. The couple is survived by four children: Charles, Anne, Andrew and Edward.

Elizabeth spent her first years as queen attempting to secure Britain’s symbolic foothold in a rapidly changing world. After her coronation, she and Philip embarked on a six-month, globe-trotting tour that spanned 13 countries in the Commonwealth of Nations, a voluntary association comprised largely of former British colonies.

“[T]he Commonwealth bears no resemblance to the empires of the past,” the queen said in her inaugural 1953 Christmas broadcast. “It is an entirely new conception built on the highest qualities of the spirit of man. … To that new conception of an equal partnership of nations and races I shall give myself heart and soul every day of my life.”

Elizabeth’s reign was marked by rocky periods of intermittent violence abroad, including Britain’s botched attempt to gain control of the Suez Canal in 1956 and the Falklands War, a ten-week-long battle with Argentina in 1982.

Closer to home, the British Army waged its longest military campaign to date: Operation Banner, an effort to establish order during the Troubles, a bloody sectarian conflict that engulfed much of Northern Ireland between 1968 and 1998. The conflict touched Elizabeth directly in 1979, when the Irish Republican Army assassinated her second cousin, Lord Louis Mountbatten.

That same year, the U.K. elected its first woman prime minister, Margaret Thatcher. As Thatcher embarked on an ambitious agenda of economic deregulation, the queen and the prime minister enjoyed a tense but respectful relationship.

Despite the tumult of post-war British politics, Elizabeth remained staunchly tight-lipped, rarely commenting publicly on current events. “[She] aggressively cultivated a reputation for being impartial,” says Brooke Newman, a historian at Virginia Commonwealth University.

“[She] aggressively cultivated a reputation for being impartial.”

Elizabeth met with the prime minister almost every week of her reign, in addition to leading the annual opening of Parliament. But her involvement in day-to-day politics was fairly limited, and she took great pains to avoid seeming publicly biased toward one political party or another. (Other members of the royal family proved more vocal than the queen: Philip, for one, earned notoriety for making inappropriate and racist comments, while Charles has spoken publicly about a number of political pet projects.)

As queen, Elizabeth instead devoted herself to diplomatic duties such as state dinners, visits with dignitaries and other acts of ambassadorship. Though she took on fewer duties over time, the queen marked a series of major milestones, including her silver, golden, diamond, sapphire and platinum jubilees—the last of which she celebrated in February 2022.

Elizabeth II and the Smithsonian

Among Elizabeth’s countless public engagements were three state visits to the United States: an October 1957 meeting with Dwight D. Eisenhower; the bicentennial of American independence in July 1976, when she was greeted by Gerald Ford; and a May 1991 trip to see George H. W. Bush. Several other U.S. presidents visited Elizabeth at Windsor Castle. In 1982, Ronald Reagan rode horses around the castle grounds with the monarch.

The queen’s 1976 visit to Washington, D.C. also included a trip to the Smithsonian Institution, says Richard Kurin, the Smithsonian distinguished scholar and ambassador-at-large. At the time, he was a young anthropologist working in his very first Smithsonian job.

“It was the 200th anniversary of the United States,” Kurin recalls. “And we had just opened the [National] Air and Space Museum, which was a big deal, because that was our country’s birthday present to ourselves.”

Curators made special arrangements for the visit, transporting the prized Hope Diamond from its high-security home at the National Museum of Natural History to the Smithsonian Castle, where the 45.52-carat diamond was placed in a temporary display case for the queen’s viewing.

Elizabeth’s visit represented a full circle moment for the Smithsonian, says Kurin. After all, an 1838 donation from Englishman James Smithson established the Institution as it’s known today. The 104,960 gold sovereigns that made up the cache bore the likeness of a teenaged Queen Victoria.

Several sources also suggest that Elizabeth’s distant relation, George IV, may have once owned the Hope Diamond himself. “Elizabeth’s predecessor may have actually possessed [the gem],” adds Kurin, who has written a book on the stone’s winding journey from 17th-century India to the U.S.

Interested in learning more about the Smithsonian’s connection with the Queen? Check out this Spotlight of stories and objects from our collections.

The royal family in crisis

The queen championed the Victorian propriety of her ancestors—a stance that increasingly placed her at odds with the rest of the royal family, whose affairs, spending habits and personal feuds became fodder for endless celebrity gossip columns by the turn of the 21st century.

Still, not even Elizabeth could fully evade criticism. The queen’s finances caught the public’s attention in 1992, when a fire burned much of her beloved Windsor Castle to the ground. British commentators balked when the government announced that taxpayers would shoulder the $90-million burden of restoration costs. In response, Elizabeth quickly announced a plan to pay taxes on her personal income—something she had never done before—and dipped into her own substantial reserves to rebuild the castle.

The 1992 fire coincided with a maelstrom of negative press for the royal family, including a flurry of highly publicized divorces and a tabloid frenzy over royal scandals. (The acclaimed Netflix series “The Crown” dramatizes many of these incidents, including clashes with prime ministers, reports of Philip’s infidelity and a break-in at Buckingham Palace.) In a rare public display of emotion, the queen dubbed 1992 an annulus horribilis—Latin for a “horrible year”—in her annual Christmas address.

In 1997, the queen attracted criticism in the press for her aloof public response to the death of her daughter-in-law, Princess Diana. More than two decades later, Diana’s son Prince Harry and his wife, American actress Meghan Markle, described how a culture of racism in the royal family led to their eventual departure from the “Firm” in a tell-all interview with Oprah Winfrey. Elizabeth responded to the allegations with a curt, 61-word statement.

The queen also met with judgment for quietly standing by her second son, Prince Andrew, as he faced a civil sexual assault case for allegedly raping a teenager in 2001. (Details of the case have since brought Andrew’s relationship with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein into harsh relief.) In January 2022, the queen stripped Andrew of his royal titles and duties. Andrew settled the case out of court for an undisclosed—but likely multimillion-dollar—sum.

The queen’s image

As the embattled royal family negotiated a seeming unending series of crises, Elizabeth maintained public favor by cultivating an image as a morally unflappable monarch.

Among her subjects, support for the queen—and the broader institution of monarchy—varied widely by age group. One recent poll found that 41 percent of 18- to 24-year-old Brits want to replace the monarchy with an elected head of state.

Elizabeth herself, however, has received consistently high public approval ratings, bolstered in the past decade particularly by supporters over the age of 65.

“When the British think about themselves and their best selves, they think about Queen Elizabeth,” Newman says. “She’s dignified, she’s inscrutable. Her feathers are rarely ruffled. She’s the face of the nation that they can be proud of.”

The queen cut an iconic, matriarchal figure. Standing just 5-foot-4, she established a uniform of bright, monochromatic outfits and hats that set her apart from the crowd. Accompanied by an entourage of corgis and, in her later years, crowned by a cloud of white hair, she became “not only the queen but the defining image of one,” as critic Guy Trebay wrote in 2012.

“She often emphasized, ‘I have to be seen to be believed,’” says royal historian Carolyn Harris. “And she meant that literally.”

Elizabeth embodied these attributes in a rare televised speech delivered during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. (Besides her annual Christmas Day addresses, the speech marked only the fifth time that she had addressed the British public in such fashion.)

“I hope … those who come after us will say the Britons of this generation were as strong as any, that the attributes of self-discipline; of quiet, good-humored resolve; and of fellow feeling still characterize this country,” said the queen, dressed in bright green with a string of pearls on her neck and a bouquet of roses in the background, in April 2020.

Some of Elizabeth’s domestic popularity can likely be attributed to a sense of colonial nostalgia that has surged in the U.K. in recent years, Newman says. While the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 prompted some Britons to dismantle symbols of colonialism, nationalist and anti-immigrant movements continue to promote a sanitized narrative of British history that overlooks slavery and glorifies imperial ambitions.

At its apex just a few years before Elizabeth’s birth, the British Empire claimed roughly a quarter of all land on Earth. European colonizers—among them enslavers, traders and investors, including members of the royal family—enriched themselves through the enslavement of African and Indigenous people and the appropriation and exploitation of colonies’ resources.

Powerful anticolonialism movements chiseled away at the British Empire throughout the 20th century, with countries from India to Kenya successfully lobbying for independence from the U.K. While the empire of her ancestors crumbled, Elizabeth dedicated herself to preserving its descendant: the Commonwealth. Officials proposed the organization, which formally coalesced around Indian independence in 1947, as a “counterbalance to the centrifugal forces that were drawing the empire apart,” writes Philip Murphy, a historian at the University of London, in Monarchy and the End of Empire.

Elizabeth strived to preserve the Commonwealth—and by extension, the monarchy’s relevancy outside the United Kingdom. She even had the symbols of various Commonwealth countries embroidered on her coronation gown. Her dedication was so evident that, in 1996, historian Frank Prochaska quipped that the queen “likes dogs, horses, the Commonwealth and her grandchildren.”

The queen was “far and away” the most-traveled British monarch of all time, visiting former British colonies by boat, train, car and plane, says Harris. She wielded her power as a diplomat and symbol of British identity to stress unity among the former colonies.

One of Elizabeth’s earliest public appearances underscored this vision. It was 1947, and the princess and her family were visiting the newly independent South Africa. (The following year, the all-white Nationalist Party would begin constructing the racist legal architecture of apartheid, codifying racial inequities inherited from decades of British and Dutch colonization.)

In a speech delivered on her 21st birthday, the heir apparent appealed to the “youth of the British family of nations” to defend the principles of liberty, peace and prosperity in their respective countries—or colonies, as many would not achieve independence until later that century.

“[I]n our time we may say that the British Empire has saved the world first, and has now to save itself after the battle is won,” Elizabeth said. “… If we all go forward together with an unwavering faith, a high courage and a quiet heart, we shall be able to make of this ancient commonwealth, which we all love so dearly, an even grander thing—more free, more prosperous, more happy and a more powerful influence for good in the world—than it has been in the greatest days of our forefathers.”

She concluded with a promise: “I declare before you all that my whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service and the service of our great imperial family to which we all belong.”

The fate of the Commonwealth of Nations

Seventy-five years later, the Commonwealth boasts 54 member countries. It functions as the “surviving remnants of the British Empire,” according to Newman, and “exists mainly as a trade and political organization.” (Membership is technically open to all countries—Rwanda, for instance, joined the fold in 2009 despite lacking historic ties to the U.K.)

Whether Commonwealth countries will continue to voluntarily continue their relationship with the crown, particularly as more countries weigh the royals’ symbolic roles as emissaries of empire, is unclear. As the primary spokesperson for the royal family, Elizabeth acknowledged but did not apologize for a long list of British imperial crimes committed in centuries past. The crown continues to deny growing calls for reparations from former colonies.

Without Elizabeth’s careful stewardship, the future of the Commonwealth hangs in the balance. The position of “head of commonwealth” that Elizabeth occupied for so many years is not hereditary and will not transfer automatically to her successor, the newly ascended Charles.

The late monarch boasted extremely high public approval ratings. Charles, by contrast, is a much more divisive public figure. The heir waited a record-breaking 70 years to ascend to the throne; his track record led some to speculate that Prince William, his eldest son, would take the crown instead.

Commonwealth leaders informally agreed to elect Charles as their head in 2018. But this could always change, Newman says.

Member states could also follow Barbados’ lead and cast off the monarchy once and for all. The island nation became a republic in December 2021 but remained part of the Commonwealth.

“The time has come to fully leave our colonial past behind,” wrote Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley of the decision. “Barbadians want a Barbadian head of state.”

Fourteen nations continue to recognize the British crown as their ceremonial head of state: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Tuvalu, Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Belize, Grenada, Jamaica, Papua New Guinea, Saint Lucia, the Solomon Islands, St. Kitts and Nevis, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. It remains to be seen whether these countries will pledge their loyalty to Charles or, pushed over the edge by the queen’s death, echo Barbados’ example.

“Elizabeth has cobbled together the Commonwealth, basically through the force of her personality, since 1952,” says Newman. But Britain’s once-dominant role in world politics has waned, and the end of Elizabeth’s platinum reign could trigger another wave of anti-colonial efforts in former British colonies near and far.

“Now,” the historian adds, “the Commonwealth could just unravel completely.”

Nora McGreevy is a former daily correspondent for Smithsonian. She is also a freelance journalist based in Chicago whose work has appeared in Wired, Washingtonian, the Boston Globe, South Bend Tribune, the New York Times and more. She can be reached through her website, noramcgreevy.com.

This article was originally published by Smithsonian. Copyright 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

Posted: 8 September 2022

- Categories: