Focus on the Future: Sally Bornbusch

Focus on the Future is a series that seeks to highlight the early career scientists who conduct research at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. Learn about undergraduate, graduate and post-doctoral fellows and the conservation research they are supporting through first-hand accounts and stories. Check back each month for more!

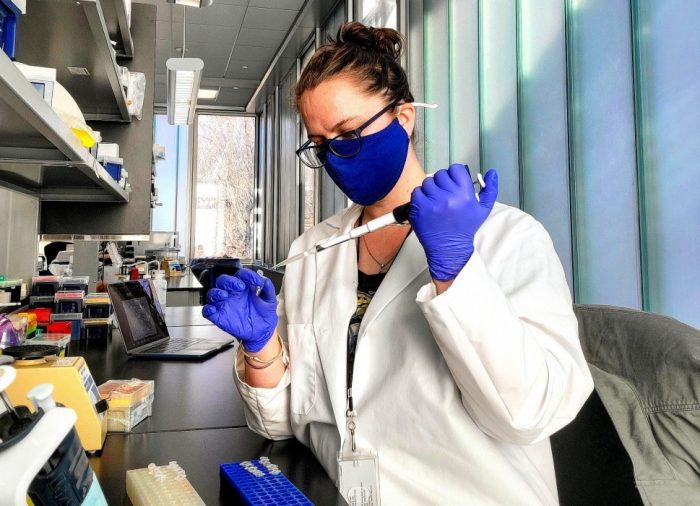

Sally Bornbusch, Ph.D.

Smithsonian George E. Burch Postdoctoral Fellow,

Smithsonian National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute

If someone had told me 10 years ago, I would have a career in microbiology, I would have laughed.

I was born in Massachusetts to a family of scientists; both my parents have their Ph.D.’s in biology. We moved to the DC area after a few years, and I grew up going to the Smithsonian’s National Zoo. The Smithsonian had always been the epitome of science in my mind. It was just the most amazing place where they did the most amazing science, and the Zoo was the coolest place to do conservation. Never in my wildest dreams did I think I would be able to work here one day.

My parents both worked for the government and their careers brought my whole family to live in Kenya when I was a child. It was an eye-opening experience for me to be exposed to the wildlife and natural beauty. It also instilled in me a desire to do international conservation work. Throughout my schooling years, I tried to do any international volunteer or science work I possibly could. I went to the College of William and Mary for undergrad. During college, I volunteered in Kenya a few times and did field work in Belize. I even studied abroad in South Africa and the Netherlands.

Microbiology was never my forte. I went to Duke University for graduate school to study behavioral ecology in lemurs. In my first year, I had to make a big 180-degree change in my research. I couldn’t do the project I had proposed for a variety of reasons, so my lab partner suggested I study microbiomes. The shift was partially by chance and partially because I had someone willing to support and mentor me.

A lot of what I do is to keep animals healthy when they are under human care and better prepare them for when they could be reintroduced into the wild. There’s so much research being done on how microbiomes can be applied to conservation strategies, whether through species reintroduction, tracking the health of wild animals or even looking at the microbiome of a reforested area to understand how it is supporting wildlife.

It’s important to know not everyone is going to have a very linear, straightforward career path. There will be obstacles, you will change what you’re interested in, your trajectory will change. Inevitably, things might go wrong! But that is normal. It is not going to be the end of your career if something doesn’t go exactly according to plan.

Posted: 5 August 2023