Summer Summary: A Mysterious Fossil Tooth, Metallic Planet and Marine Hitchhikers

Catch up on the National Museum of Natural History discoveries you may have missed over the past few months.

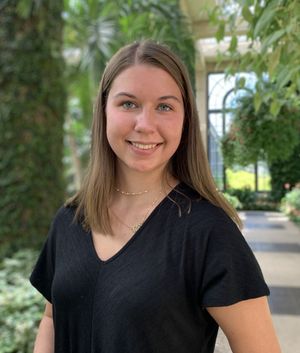

Smithsonian researchers rediscovered a tooth from an ancient hippo-like marine mammal in the museum’s collection. To pinpoint where the tooth was unearthed, the team analyzed archival material including this black-and-white photo of the digsite (left). (Kumiko Matsui, NMNH)

While summer in Washington is peak vacation season, researchers at the National Museum of Natural History are maintaining their rapid rate of scientific discovery. Over the past few months, museum scientists have named a new black coral species, described a constellation of Antarctic sea stars from the museum’s collection and even found potential fossil evidence of cannibalism amongst our ancient human relatives.

But that’s only a fraction of what museum scientists have been working on. To help get you caught up on the summer research you may have missed, Smithsonian Voices is spotlighting a few intriguing findings from the past three months.

A mysterious molar sheds light on odd group of marine mammals

A fossil molar that was rediscovered in the museum’s collection. (Jack Tamisiea, NMNH)

When postdoctoral researcher Kumiko Matsui was looking through a cabinet in the museum’s paleobiology collection during the summer of 2021, she was surprised to come across a forgotten fossil tooth deposited in one of the drawers. She knew it belonged to a desmostylian, an extinct group of marine mammals that inhabited coastlines along the Pacific Rim. These hippo-like herbivores had a mouthful of oddly shaped molars that resemble a bundle of rods encased in thick enamel.

But identifying the ‘Desmo’ species the tooth belonged to was more difficult. The fossil was originally discovered by Warren Addicott, a paleontologist at the United States Geological Survey, in 1965. To pinpoint the exact rock formation where Addicott uncovered the curious chomper, Matsui and Nicholas Pyenson, the museum’s curator of fossil marine mammals, examined archival museum records, including a faded, handwritten label and a sepia-tinted photograph of the digsite.

This helped them trace the tooth back to Northern California’s Skooner Gulch Formation. This site, which dates back between 22 and 23 million years to the early Miocene Epoch, has also yielded fossils of extinct megamouth sharks, early toothed whales and the prehistoric precursors to modern seals and sea lions.

In June, Matsui and Pyenson published a description of the rediscovered fossil tooth in the journal Royal Society Open Science. They linked the tooth to Desmostylus, a type of desmostylian previously thought to originate much later in the Miocene. According to Matsui, the fossilized molar reveals that Desmostylus sported these specialized, column-like teeth for more than 15 million years.

A fishy friendship emerges as scientists discover a new pair of open-ocean dive buddies

This spotted driftfish is engaged in a commensal relationship with the nudibranch, taking advantage of the shelter in open water but introducing no benefit or harm to the sea slug. (Linda Ianniello, blackwater diver)

Smithsonian vertebrate zoologists Murilo Pastana and David Johnson described this commensal relationship, the first recorded instance of a bond between these two species, in a study published in the Journal of Fish Biology in August. Their work sheds light on the little-known early life history of driftfishes and nudibranchs. The project also spotlights the vital role blackwater divers and other community scientists play in capturing rare behaviors.

For human-harvested shellfish, it’s the survival of the tastiest.

Bivalve mollusks have been feeding humans for millennia, and managing populations to prevent overharvesting has become more important than ever as shellfish demands increase. (Brittany M. Hance and James D. Tiller, NMNH)

No summer menu would be complete without a savory shellfish entree, and surprisingly, the supply of these ocean delicacies never seems to dry up. The typical table may feature favorites like clams, oysters, and mussels. However, new research by museum paleobiologist Stewart Edie has expanded the list of human-harvested bivalves to an impressive 801 species that are eaten around the world.

In a study published in Nature Communications in August, Edie and his colleagues revealed how the same traits that turn shellfish into seafood staples also help them resist extinction. Specifically, these species are larger in size and live in a wide range of shallow water ecosystems, where they have adapted to withstand natural drivers of population decline. While this may seem like a win-win, Edie stresses that humans can transform ocean environments in the blink of an eye, and sustainable management will be the key to protecting these species for generations to come.

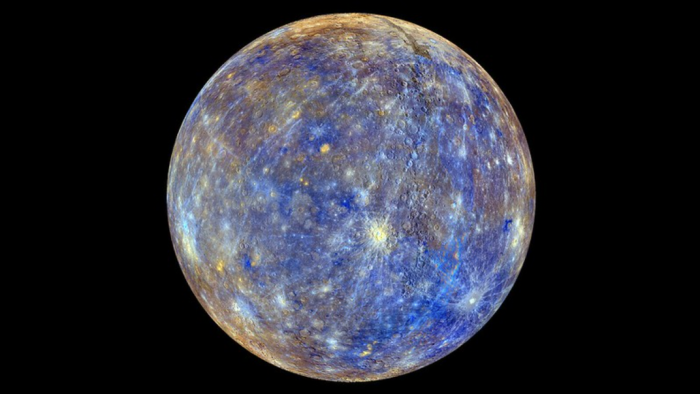

A chromium core reveals secrets about Mercury’s mysterious origins

Mercury’s metallic core makes up 85% of its total volume, compared to Earth’s core which accounts for only 15% of its volume. NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington

The desert world of Mercury is the closest to our sun, the smallest in size, and has the largest core of any planet in our solar system. Mercury is also one of the least understood planets, and its origins have remained enigmatic to scientists for centuries. However, a study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets in June offers new insights into Mercury’s geological past and unique elemental make-up.

Genetic clues help identify new species among coral lookalikes

A colony of Acropora tenuis, a species of staghorn coral long thought to live throughout the Indo-Pacific region. MDC Seamarc Maldives

Since the 1980s, scientists have thought that the staghorn coral Acropora tenuis is one of the planet’s widest ranging reef-builders. The coral, whose colonies grow in spiny clusters, was considered to occur across the Indo-Pacific from Africa to Tahiti and as far north as Japan.

A team of researchers including Andrea Quattrini, the museum’s curator of corals, recently examined the DNA of several A. tenuis museum specimens. They discovered something surprising: the seemingly cosmopolitan coral only occurs in the South Pacific around Fiji and Tonga. A. tenuis coral found elsewhere actually belonged to different species with much smaller ranges. The similar appearances of many of these staghorn corals had obscured their unique identities for decades before the team compared the corals’ genetic codes.

In a paper published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society in July, Quattrini and a group of collaborators from around the world including Australia’s Queensland Museum and James Cook University described this hidden diversity and named two new species of staghorn coral from the Great Barrier Reef and the South Pacific’s Cook Islands. While the work boosts the number of known coral species, it also raises conservation concerns. With reduced ranges, these staghorn coral species may be more vulnerable to extinction than previously thought.

______________________________________________________________________

Posted: 9 September 2023

-

Categories:

Feature Stories , Natural History Museum , Science and Nature