Got an object and want to know what it’s made of? Send it to Asher Newsome

![]() “Can you ‘science’ this?”

“Can you ‘science’ this?”

Asher Newsome gets this question a lot. He’s one of the Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute’s chemists, and he’s good at ‘sciencing’ historical objects.

The Smithsonian has more than 157 million objects and specimens in its collection, and in real terms, part of Asher’s job is to take those objects and to learn more about what they’re made of. By studying what chemicals make up an object or sit on its surface, the MCI can piece together how it was made, learn about its place in history, and discover the most effective ways to preserve it for future generations to study and enjoy.

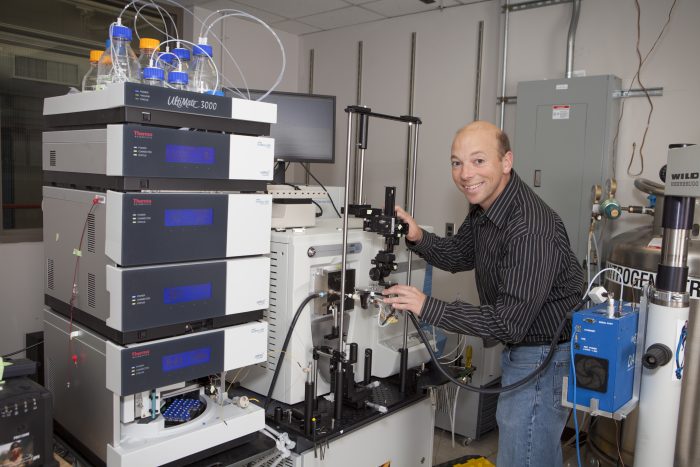

Asher Newsome with some of the equipment he uses at MCI to analyze the composition of objects from the Smithsonian’s collections.

“I’m there to determine what a substance is and how much of that substance is there. I use a technique called mass spectrometry, which is fundamentally just weighing a molecule. If you know how heavy a molecule is, you know what chemical it’s made of, and you can also figure out how much of it is there. We can apply this technique to all sorts of things. For example, if I examine something that’s been painted, I can figure out what colorant was used. If we have a plant specimen, I can figure out if a pesticide was applied, and if so, what kind.”

Asher isn’t the only one at MCI studying the Smithsonian’s collection. A few weeks ago, his colleagues were using X-rays to examine original Daguerreotypes, the first commercialized form of photographs from the mid-1800s, to see what metals were used in their production. (Hint: if you were a photographer back then, you’d likely suffer from heavy metal poisoning.)

Asher Newsome and 2021 intern/2023 postdoc Hannah Lawther working on an illuminated manuscript from 1604. (https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jasms.3c00098)

Given the number of reasons one might want to know the composition of an object, MCI ends up supporting all sorts of organizations. They primarily help Smithsonian conservators, scientists, and curators, but they also work with other government agencies (research scientist Christine France, for example, has performed forensic work for various law enforcement agencies and non-profits like the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children), other museums and cultural heritage organizations, and other organizations that appeal to the Smithsonian’s mission and values.

Asher is one of the MCI’s mass spectrometry experts (remember: weighing molecules to see what they are), and he couldn’t be a better fit for the job. Asher grew up in a rural county in the middle of Georgia and studied what science was available. He picked chemistry, as it was the next logical step for a college major. “It wasn’t until my second year that I was given problems such as ‘given this mixture and all the information you have, what molecule is this?’ and I really enjoyed that,” he said. In graduate school, he learned the hardcore fundamentals – and I mean the hardcore ‘why would anyone need to know this?’ kind of stuff. Although this left him with zero knowledge about cultural heritage when he started at the MCI, he had the talent and skills he needed to study one of the world’s most prized historical collections without causing harm to it.

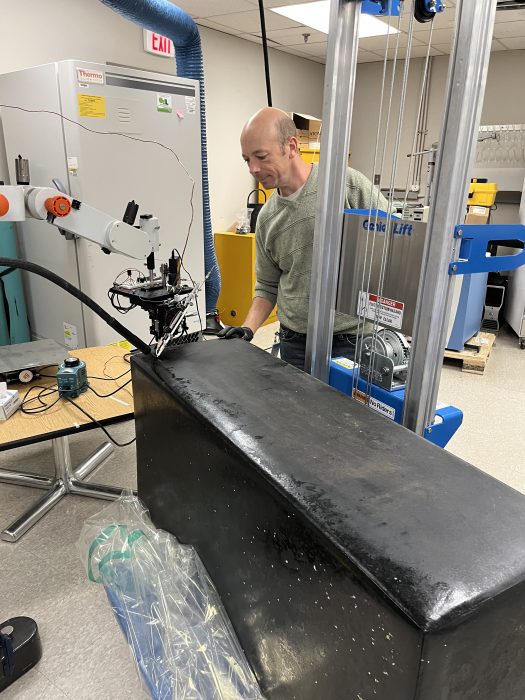

Asher Newsome examines a basket (NMAI 090037.000) from the collections of the National Museum of the American Indian.

“It was a great technical challenge for me. Usually, analyzing something with a mass spec requires that you take a sample of it. But you can’t do that with most items in the Smithsonian collection. If you’re not able to burn, cut, or dissolve something, what do you do?”

That’s when Asher decided he needed to create something new. He’s had to modify standard mass spec methods to solve two problems: first, he needed it to make it work with a sample so small that one would not be able to detect its absence from an object with the naked eye. We’re talking on the nano-level. Second, he needed to figure out how to analyze objects that didn’t fit inside the instrument, which is basically a big box.

“I’ll make sure not to go beyond whatever a curator or conservator says is okay. If they’re okay leaving a little wet spot that’s under a millimeter in scale, I can work with that. If they don’t want to leave any visible mark, that’s okay – that’s something we’ve been able to start doing recently.”

Asher Newsome prepares to examine a bench-like object from the American Art Museum’s collections.

Asher counts himself as lucky, being able to innovate like he has so he can properly study the Smithsonian’s collection. “We’re building solutions to solve problems that haven’t been solved, but there’s still a lot of room to grow. Cultural heritage work is not usually the best funded in the world, so most labs that do this are working with technology that was top of the line decades ago. We’re fortunate to have access to more advanced technology, which is rare.”

Asher’s passion for mass spectrometry is not contained to his laboratory. He was on the American Society for Mass Spectrometry’s (ASMS’) history committee, where he traced how the society has changed demographically from the 1960s. He analyzed the demographics of the Society’s leaders and those who organized its talks over time (i.e. the makeup of those who picked the speakers). Recently, he was nominated to serve as a member-at-large on the ASMS national board.

“I do this work for ASMS because I care quite a lot about the society its membership. I want the society to be better.”

And Asher is certainly doing his part, dedicating his life to a powerful piece of technology that provides answers for countless clients. His impact will only grow as he does “science” on the Smithsonian’s collection, one object or specimen at a time.

___________________________________________________________________

Eye on Science, our new biweekly series, will shine a light on our vast and varied body of work by bringing Smithsonian science into sharper focus. Eye on Science will tell the stories of the people behind the research, the discoveries they make and their inspiration. We will explore their passions, celebrate their contributions, and look more closely at how questions become solutions that can inform environmental policy, spur technological innovation, and promote community and collaboration across the globe.

Posted: 6 December 2023

-

Categories:

Eye on Science , Feature Stories , Museum Conservation Institute , Science and Nature