Meet the Archaeologist Leading the Natural History Museum’s Repatriation Efforts

With more than 20 years of experience at the Smithsonian, Dorothy Lippert is championing a collaborative approach to repatriation.

Dorothy Lippert holds a stick used to play stickball, a traditional sport among the Choctaw and other southeastern tribes. Her shirt has a traditional Choctaw design on it representing the patterned scales of a diamond backed rattlesnake. (Courtesy Dorothy Lippert,) NMNH

Dorothy Lippert was certain she wanted to be an archaeologist since she was twelve and unearthed ancient bits of charcoal and stone tool flakes while sifting through dig sites near her home in Texas. But it was not until she was studying archaeology in graduate school in the 1990s that Lippert discovered that repatriation was her true calling.

Federal laws supporting repatriation, the return of human remains and cultural items housed in museum or university collections to descendant communities, had recently been passed and Lippert remembers the topic being discussed throughout her archaeology courses. These discussions were much different from the repatriation conversations Lippert, who is a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, was having with other Native Americans.

“I was hearing both sides when not many other people were,” Lippert recalled. “Because of this, I thought I could potentially help create some understanding.”

Lippert recently became the program manager of the National Museum of Natural History’s Repatriation Office. For more than 30 years, the museum’s repatriation office has worked with Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian communities to return remains and sacred objects deposited decades, or even centuries ago, in the Smithsonian’s collection. Lippert, who previously served for more than 20 years as a tribal liaison in the museum’s repatriation office, is the first woman and first Native American to hold this position.

In this month’s installment of Meet a SI-entist, Smithsonian Voices spoke with Lippert to learn more about her experiences at the Smithsonian and the future direction of the museum’s repatriation program.

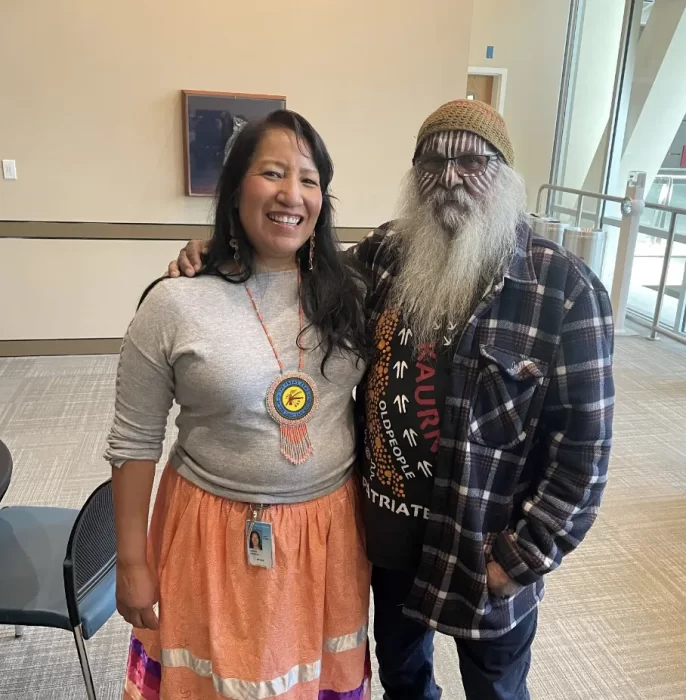

Lippert and Major “Moogy” Sumner, a Ngarrindjeri Elder and an ambassador for Aboriginal arts and traditional culture, after a recent repatriation ceremony at the museum. (courtesy Dorothy Lippert, NMNH)

First off, we’d love to learn how you first became interested in archaeology.

When I was pretty young, I remember watching a PBS show on dinosaurs and paleontology. They showed someone excavating dinosaur bones. And the guy unearthed a little bit of the fossil and he pointed to the spot and said, ‘That spot right there hasn’t seen sunlight for millions of years.’ I remember thinking, ‘that is so cool to be the person that can do that.’ That’s when I got interested in working in a field that deals with the past. I like dinosaurs, but I really like people. So I gravitated towards archaeology.

What inspired you to work in repatriation?

I began working on repatriation when I was in graduate school. Archaeologists had been arguing with tribal members and with museum organizations about the need for repatriation. The tribes were saying that repatriation is a human rights issue. There was a lot of talking, but people weren’t really hearing each other.

And I was right in the middle of that. I would go to an intertribal organization meeting and I’d hear all of these opinions. And then I’d go back to my classes in grad school with archaeologists and hear different opinions. I felt like one of the few people hearing both sides. I realized that if I could talk about repatriation from this perspective, maybe people will begin to understand it a bit more.

In addition to her work on repatriation, Lippert is a prolific scholar exploring subjects ranging from the archaeology of the Southeastern U.S. to the development of Indigenous archaeology worldwide. (Courtesy Dorothy Lippert, NMNH)

What are some of the challenges of overseeing repatriation efforts at the museum?

It’s challenging because of the extent of the museum’s collections. We’re working with Native American individuals and their belongings that need to go back to the tribes. But there are 574 federally recognized tribes that are involved that we need to be accountable to. For a long time we had two people trying to work our way through all of these requests, which is a huge challenge.

But there’s also benefits to working with so many tribes on repatriation. When tribal representatives come to the museum and talk to us, we always learn more. And so we get so many new perspectives from all these tribes that hadn’t really been in place at the museum before.

In November, we had visits from a tribe in Alaska and a tribe in Arizona. We were looking at items in the collection and having conversations and it provides us with more knowledge and information about the collections. It helps the museum do better in our work.

Do any particular repatriation experiences from your time at the museum stick with you?

The one repatriation that really sticks with me, and I think always will, is a repatriation we did for my own tribe, the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. When I learned that a Choctaw woman’s remains were at the museum, I made a promise that I wouldn’t leave the museum until I had seen her return home safely. When I was finally able to do that, it was so rewarding to me to be able to keep that promise to her. I always remember that moment when we finally completed the re-burial.

Lippert and former NMNH fellow Jen Byram at the Choctaw Nation’s annual fair, where they were demonstrating traditional textile production. (Courtesy Dorothy Lippert, NMNH)

Do any particular repatriation experiences from your time at the museum stick with you?

The one repatriation that really sticks with me, and I think always will, is a repatriation we did for my own tribe, the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. When I learned that a Choctaw woman’s remains were at the museum, I made a promise that I wouldn’t leave the museum until I had seen her return home safely. When I was finally able to do that, it was so rewarding to me to be able to keep that promise to her. I always remember that moment when we finally completed the re-burial.

This can improve the whole institution. The Smithsonian was founded ‘for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.’ But for a long time, we were not including tribal perspectives and Indigenous knowledge and science. And so it wasn’t true knowledge. With a greater inclusion of Indigenous voices, I think the Smithsonian is positioned to truly increase the knowledge that it provides.

How has the field of repatriation changed since you began working at the Smithsonian? How do you hope to help influence the future direction of repatriation through your new position?

Posted: 3 December 2023

-

Categories:

Collaboration , Feature Stories , History and Culture , Natural History Museum , Science and Nature