Love and derision: Or, Valentine’s Day Victorian Style

Valentine’s Day may be all flowers and chocolate today, but guest blogger Catherine Golden, writing for the Postal Museum, shows how the Victorians enjoyed vinegar as much as honey.

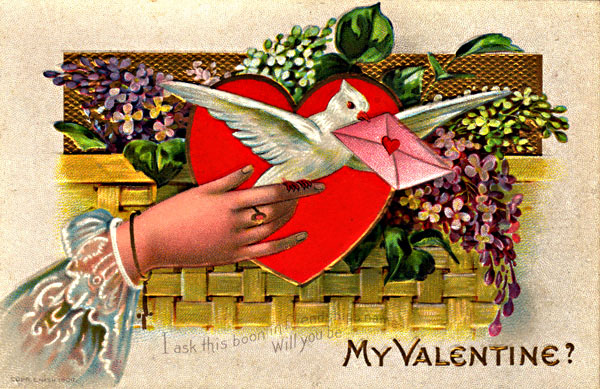

The opening issue of Household Words (March 30, 1850) includes an amusing article entitled “Valentine’s Day at the Post-Office,” written by Charles Dickens with his assistant editor, W. H. Wills. Fascinated by the influx of letters passing through the General Post Office in London, Dickens and Wills describe in detail “the sacrifices to the fane of St. Valentine—consisting of hearts, darts, Cupid peeping out of paper-roses, Hymen embowered in hot-pressed embossing, swains in very blue coats and nymphs in very opaque muslin, coarse caricatures and tender verses.” The Valentine’s Day card tradition began in earnest in England in 1840 with the coming of the Penny Post and the prepaid postage stamp, both credited to Rowland Hill.

Prior to this time, postage was high. The receiver paid for the letter, not the sender, as is the practice today. Prepayment was considered a social slur on the recipient. For the working class, a letter could cost more than a day’s wage. Leaving home often meant losing touch with one’s family and friends. But that changed on January 10, 1840, opening day of the Penny Post. All mail weighing up to one-half ounce could travel anywhere in the United Kingdom for only a penny. The United States quickly followed in 1847 with affordable mail and postage stamps. The Penny Post also had a profound impact on the sending of valentines. While the exchange of Valentine’s Day cards long predates Victorian times—legend has it that the Duc D’Orléans started the tradition in 1415 by mailing his fiancée a missive while imprisoned in the Tower of London—the reduction of postage made sending valentines affordable for the masses: in 1841, one year after Uniform Penny Postage, 400,000 valentines were posted throughout England. By 1871, three times that number passed through the General Post Office in London alone. One popular Victorian poem written around 1840 and attributed to James Beaton humorously predicts how sending valentines will peak following postal reform: “The letters in St. Valentine so vastly will amount, Postmen may judge them by the lot, they won’t have time to count; They must bring round spades and measures, to poor love-sick souls Deliver them by bushels, the same as they do coals.”

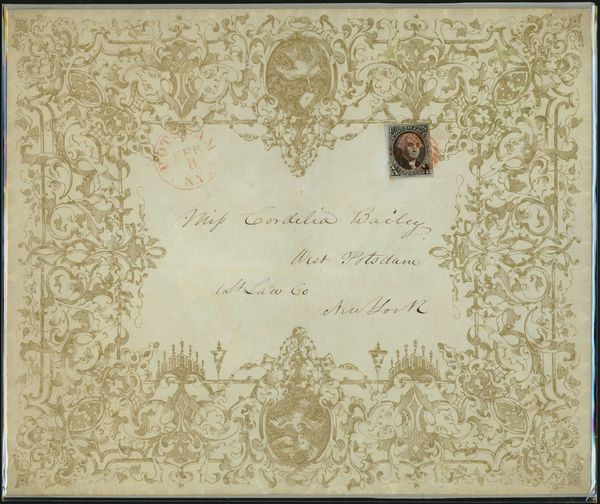

This New York valentine sent sometime between 1847-1850 was sent with a 10-cent black Washington stamp.

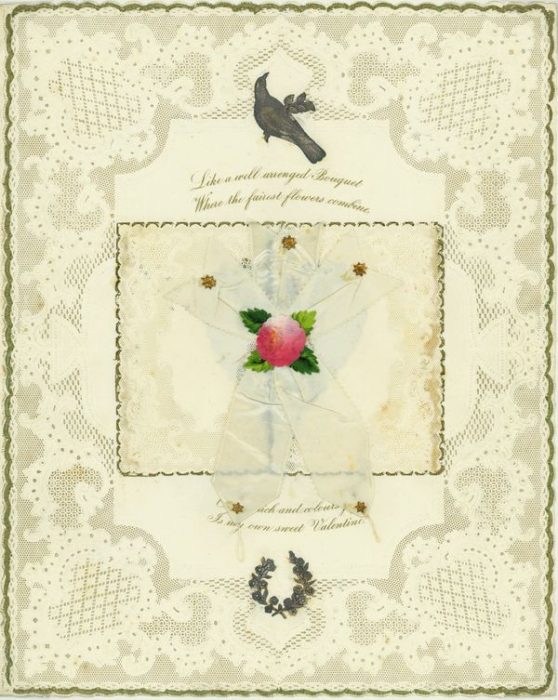

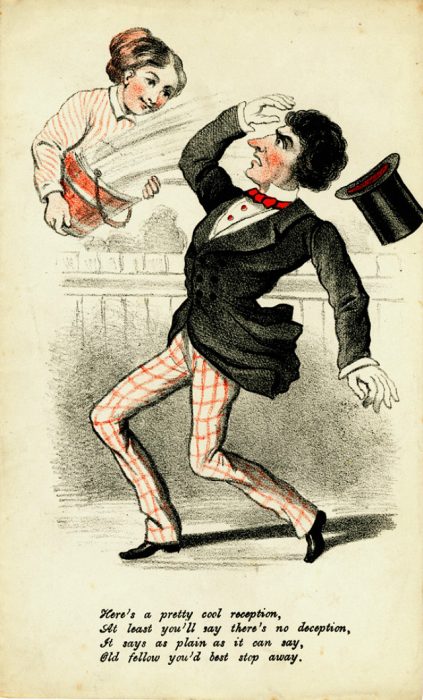

Not only did the number of valentines “vastly amount;” so did the variety of cards delivered by “spades” and “bushels.” In my analysis of Victorian valentines in the Bath Central Library in Bath, UK, I discovered “tender verses” adorned with hearts, cupids, flowers, angels, swains, and nymphs—emissaries of love—and numerous handmade missives. Rather than purchase a ready-made valentine, Victorian men and women often assembled original valentines from materials purchased at a stationer’s shop: lace, bits of mirror, bows and ribbons, seashells and seeds, gold and silver foil appliqués, silk flowers, and clichéd printed mottoes like “Be Mine” and “Constant and True.” Victorian valentines commonly feature churches or church spires, a way to signify honorable intentions and assure a betrothed of fidelity in love. But the “coarse caricatures,” as Dickens and Wills call them, may startle readers today. Valentines insult a lady as well as a dandy for poor fashion sense: “Pray don’t take offense, Nor to anger incline, In dress show more sense, You queer valentine.” Others tells a suitor he has no chance in courtship: “Oh, what dreary, senseless twaddle Issues from his empty noddle, Fantastic pubby-booby hence I’ll love you, sir, on no pretence.”

The inside of the above valentine features a sentimental verse that begins “Like a well arranged bouquet/ Where the fairest flowers combine…”

Not all Victorian valentines are this polite about telling a suitor to butt out: “Don’t think yourself so vastly killing Little men I quite despise And I never shall be willing To accept one of your sighs.” Valentines tease bachelors about remaining single and urge them to marry: one valentine shows a perfect stocking above a torn one and reads, “High Hose! Or the Inconvenience of an Unmarried life. Never too late to mend;” another features a gentleman bungling an attempt to mend his trousers: “For a Bachelors troubles who should care He ought to get married they all declare. If a button comes off, he must sit up in bed, And make a sad bungle of needle and thread. But if he’d take courage and also a wife, He’d find ‘twas the happiest day of his life.” When a viewer pulls a tab in this mechanical valentine, the bachelor nods his head in agreement. Marriage was also ripe for ridicule. In a card entitled “A PEEP THROUGH THE WEDDING RING,” a bride teases her groom: “I think you love me, it is true And well, perhaps it may be, But if we’re married, say will you, Object to nurse the baby.” Even the Victorian postman, hurrying from spot to spot to deliver bushels of valentines to love-sick souls by the spades, was not exempt from scorn. One coarse caricature-style card laughingly reads: “With child like coat of glaring red, And hat of felt on empty head, In rain or wind compelled to trot, Drudge like, hurrying from spot to spot.”

Here’s a pretty cool reception,/At least you’ll say there’s no deception,/It says as plain as it can say,/Old fellow you’d best stop away.

Unlike the Victorian era, insulting valentines have all but vanished from our card shops, and handmade valentines appear most frequently in elementary school classrooms. But just as in Dickens’s time, on Valentine’s Day we depend on the Post Office to deliver our heartfelt wishes by the bushel.

Guest blogger Dr. Catherine Golden is professor of English at Skidmore College and author of Posting It: The Victorian Revolution in Letter Writing (2009). Her talk at the National Postal Museum can be seen on the museum’s YouTube channel. This post was originally published by the museum’s blog, “Pushing the Envelope”

Posted: 14 February 2024

- Categories: