Newly discovered fossil from the Smithsonian’s collection named after Kermit the Frog

The new amphibian ancestor joins a growing list of species named after Jim Henson and his Muppet characters.

Researcher Calvin So holds the fossil skull of Kermitops, a new species of ancestral amphibian discovered in the museum’s collection, next to the Kermit the Frog puppet on display in the Entertainment Nation exhibition at the National Museum of American History. James D. Tiller and James Di Loreto, Smithsonian

Kermit the Frog is the most recognizable amphibian in the modern era. From his beginnings as the host of “The Muppet Show” to a modern-day meme icon, Kermit’s cartoonish voice and green complexion are instantly recognizable. Now, in recognition of Kermit’s celebrity status, researchers are naming a fossil from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History’s collection after the iconic puppet.

In a paper published March 21 in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, museum paleontologist Arjan Mann and Calvin So, a doctoral researcher at George Washington University, describe a new species of proto-amphibian that they recently discovered in the museum’s fossil collection. They identified several unique features on the animal’s skull that required them to create an entirely new species. So, they decided to draw inspiration from the world’s most famous frog and name the discovery Kermitops gratus.

Kermitops was originally collected in 1984 during an expedition in Texas by Smithsonian paleontologist Nicholas Hotton. But Hotton and his team collected so many fossils at the time that they could only examine a fraction of them. When Mann was sifting through some of Hotton’s fossils in 2021, a nickel-sized skull of an ancient amphibian ancestor caught his eye. He teamed up with So to take a closer look, and the two ended up discovering a new member of the amphibian extended family tree.

The fossil skull of the ancient amphibian ancestor Kermitops gratus (left) alongside a modern frog skull (Lithobates palustris, right). Brittany M. Hance, Smithsonian

Kermitops gratus joins a growing group of species named after famed puppeteer Jim Henson and his lovable Muppet and Sesame Street characters. Several of Henson’s most famous puppets are now housed in the collection of the National Museum of American History. From sea slugs to spiders, researchers all over the globe have been inspired to come up with Muppet-themed monikers for their new discoveries.

Ariadna gonzo (Gonzo)

Muppet daredevil Gonzo (right) was the inspiration for Ariadna gonzo because his hook-shaped nose resembles the tip of the spider’s front limbs. Copyright United States Postal Service. All rights reserved.

This Tasmanian tube-dwelling spider gets its name from the Muppet stuntman Gonzo. Tube-dwelling spiders spin cylindrical webs in between two solid surfaces, like a crack, to capture their prey. They are found all over the world, but this species was first described by scientists in 2022.

The name was inspired by the hook-shaped tips of the spider’s pedipalps, which the scientists thought resembled the shape of Gonzo’s beak. The pedipalps are the spider’s front appendages. They are similar to antennae in that they help the spider sense obstacles in its path. The hook-like structure at the tip of these leg-like limbs is a sexual organ that helps transfer sperm from a male spider to a female spider.

Stelis oscargrouchii (Oscar the Grouch)

Oscar the Grouch, the fuzzy resident of Sesame Street’s garbage cans, was partially inspired by a rude waiter Henson encountered at a restaurant named Oscar’s Salt of the Sea. Gift of Muppets, Inc.

While the orchids you might be most familiar with are the pink and purple garden varieties, the orchid family is actually a diverse botanical group that encompasses plants from around the world. One member of this family is Stelis oscargrouchii, a miniature orchid described in 2015 and named after Henson’s Oscar the Grouch character from Sesame Street.

This delicate plant is native to Ecuador and grows best in a tropical, wet climate. The small, green and fuzzy flowers reminded the researchers of the trash-dwelling, curmudgeonly puppet.

Hensonbatrachus kermiti (Kermit and Jim Henson)

The star and host of The Muppet Show, Kermit was created by puppeteer Jim Henson in 1955. This Kermit the Frog puppet is on display in the Entertainment Nation exhibition at the National Museum of American History. Gift of Jim Henson Productions

Like Kermitops, this species of fossilized amphibian, which was named in 2015, honors the iconic Kermit the Frog. The scientists also named the genus after Henson, doubling up on the Muppet mania.

The researchers analyzed fossilized bones from the creature’s skull, pelvis and upper arm to identify Hensonbatrachus kermiti as a new species. The frog lived in Alberta, Canada, in the late Cretaceous Period, between 85 and 65 million years ago. It was up to 4.5 inches long, about the same size as two golf tees lined up end to end, and had lots of tiny teeth.

Olea hensoni (Jim Henson)

As one of the few known sea slugs that eats the eggs of other invertebrates, Olea hensoni was a notable find for more than just its connection to the Muppet creator. Gustav Paulay, Florida Museum

This slimy slug, which hails from an island just south of Florida, was discovered by researchers in 2019 and named after Henson himself. It belongs to a group of slugs called sacoglossans, most of which feed on plants. The scientists came up with the name because the slug is brown-ish yellow color, while other slugs in the group are green. This reminded them of Kermit the Frog’s song “It’s Not Easy Being Green.”

However, its color and famous namesake isn’t the only thing that sets Olea hensoni apart from its relatives. Instead of eating plants, it consumes the eggs of other slugs and snails. There are only two other species of “egg-sucking” slugs in the world, and Olea hensoni’s closest relative lives in the northeast Pacific Ocean. The researchers think this is evidence that the new slug is part of an older lineage of formerly widespread egg-sucking slugs that gradually dwindled to only a few isolated species over time.

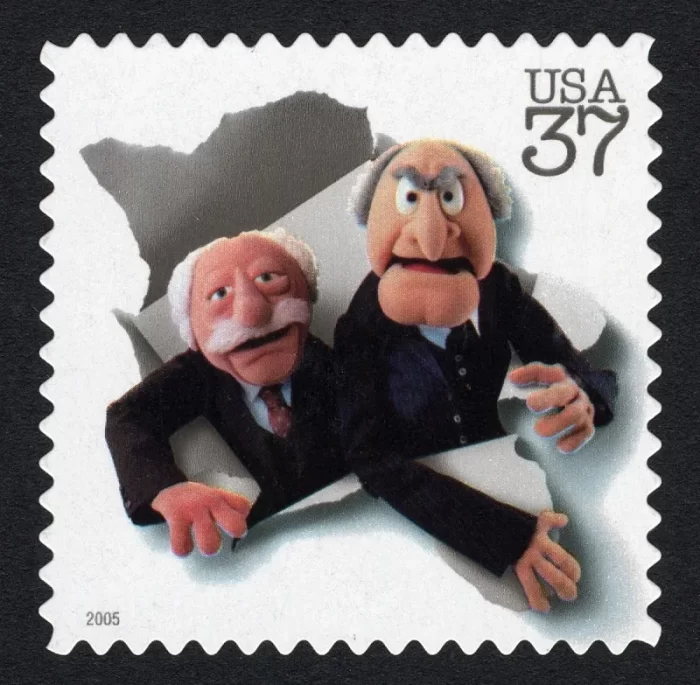

Geragnostus waldorfstatleri (Statler and Waldorf)

The Postal Service commissioned a series of Jim Henson-themed stamps in 2005 that featured several of his most famous creations, including Fozzie Bear, Miss Piggy, Swedish Chef and Statler and Waldorf, pictured here. Copyright United States Postal Service. All rights reserved.

Discovered in 2005 in China, the name of the trilobite species Geragnostus waldorfstatleri is a nod to the Muppet hecklers, Statler and Waldorf. Trilobites are a group of extinct arthropods that lived from the Cambrian to Permian periods. More than 22,000 species of trilobites have been identified by paleontologists thanks to the hard exoskeletons they left behind.

Like insects, trilobites have three morphological sections: the cephalon (the head), thorax and the pygidium (tail). The paleontologists who described Geragnostus waldorfstatleri thought that the pygidium of this species looked like the heads of these grumpy Muppet characters. This catapulted Statler and Waldorf from the box seats into the scientific record.

Emily Driehaus is a Science Writing Intern with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. She holds a master’s degree in science journalism from New York University and has worked as a journalist and science writer covering everything from microbiology and climate change to particle physics and quantum computing. Her writing has been published in Sierra Magazine, Symmetry Magazine, VICE News, and other outlets.

This post was originally published by the Smithsonian magazine blog, Smithsonian Voices. Copyright 2024 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

Posted: 25 March 2024

-

Categories:

Feature Stories , Natural History Museum , Science and Nature