Why do we celebrate Memorial Day?

A Civil War military history researcher explains where Memorial Day celebrations came from.

n the midst of the nation’s observation of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, battle anniversaries and encampments of Union and Confederate reenactors are reminders of the Civil War’s long legs in American society. One of the lesser-known legacies of the Civil War, however, is Memorial Day.

The holiday has its roots in local commemorations of the fallen soldiers of that war, many of which involved laying flowers on graves and paying tribute to the fighting men who gave the last full measure for their cause. The first Memorial Day observances were notable for having been organized by those Americans who were unable to fully participate in the conflict that defined their era: women and African Americans.

One of the most important antecedents of the modern Memorial Day was a Decoration Day organized by freedman’s relief organizations and formerly enslaved people in Charleston, South Carolina, on May 1, 1865. One of a series of celebrations in the destroyed city to mark the end of the war, this event was orchestrated by the African American citizens of Charleston to mark and decorate the graves of the 257 Union prisoners who died at the Charleston Race Course, which had been converted to a Confederate prison. Thousands of freedmen, including almost 3,000 black schoolchildren, gathered to decorate the graves with flowers and beautify the graveyard, building an enclosure and an arch labeled, “Martyrs of the Race Course” in what is now Hampton Park. Scholar David Blight has christened this event the first Memorial Day: “What you have there is black Americans recently freed from slavery announcing to the world with their flowers, their feet, and their songs what the War had been about. What they basically were creating was the Independence Day of a Second American Revolution,” he said in a recent speech.

Meanwhile, women in both northern and southern states had contributed to the war effort by managing farms and businesses, producing necessary war supplies, joining voluntary associations like the United States Christian Commission and the Women’s Relief Society, and maintaining family life on the home front. Popular conceptions of femininity in American life held that women should perform the emotional work of grieving and mourning deceased family members. With thousands of fathers, brothers, and sons dying in combat every month, women adapted their responsibilities to this grim new culture of death. Americans were embracing the Victorian rural cemetery ideal, in which families would visit their deceased loved ones in tree-shaded parks to emphasize perpetual remembrance and rest.

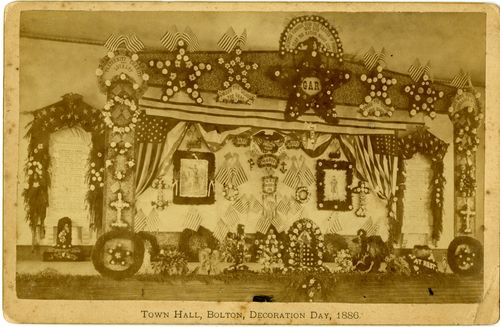

During the Civil War, some women began decorating soldiers’ graves with flowers, a custom which may have been borrowed from German Catholic observances on All Saints’ Day. Dozens of cities in both northern and southern states claim to have been the birthplace of the Decoration Day tradition, but it had become an annual spring tradition in many cities by the end of the war. Whereas the United States government established National Cemeteries and funded projects to identify and reinter Union casualties after the war, in the former Confederacy, ladies’ memorial associations took up the task of marking and maintaining graves in the absence of a sympathetic government.

The Columbus Ladies’ Memorial Association, which maintained a Confederate graveyard in the eponymous Georgia city, first called upon Southern women to observe Memorial Day in an open letter published in March 1866. Though the date and local traditions varied by town, within several years communities across the country were remembering veterans of the war with speeches, exercises, and parades which usually culminated with women decorating graves in the local cemetery.

In the post-war Reconstruction era, women were often credited with preserving the solemn and conciliatory nature of the festivities.

“It is the more impressive when the day is not observed by any noisy demonstration or pompous ceremonies, such as men are wont to use in making known their respect for the heroic dead, but when woman’s warm heart impels the observance, and the tribute paid to departed valor is only the placing of Spring’s brightest flowers upon the graves in which the soldiers’ bones repose,” wrote the Richmond Dispatch in a Memorial Day editorial published in 1870.

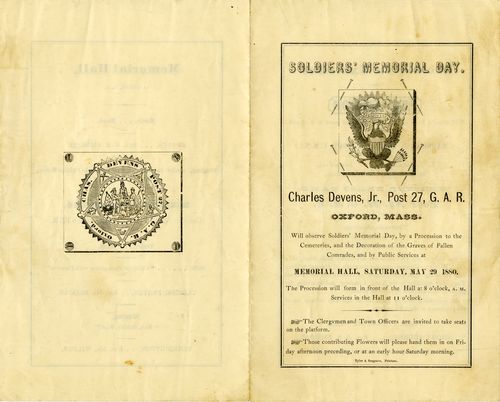

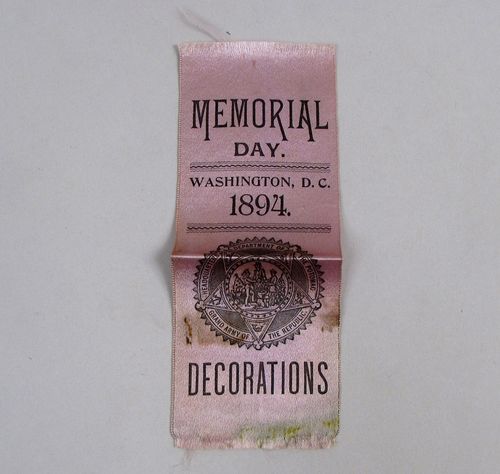

On May 5, 1868, the Grand Army of the Republic called for a regular national Memorial Day celebration. Major General John A. Logan wrote for the veteran’s organization that, “we should guard their graves with sacred vigilance… Let pleasant paths invite the coming and going of reverent visitors and fond mourners. Let no neglect, no ravages of time, testify to the present or to the coming generations that we have forgotten as a people the cost of a free and undivided republic.”

As the more rancorous memories of the conflict faded, Southerners and Northerners began to celebrate Memorial Day together, although it did not become a federal holiday until 1971. Many Americans still visit family gravesites with flowers on the last weekend in May, although for many the holiday has come to mean the beginning of summer, cookouts, and a day to spend relaxing with loved ones.

This post by Ryan Lintelman was originally published by the museum’s blog, O Say Can You See?

Posted: 27 May 2024