Political history curators from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History are at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee, collecting items from clothing to signs that will help tell the story of the 2024 presidential election. Conversation U.S. politics editor Naomi Schalit interviewed them last week, before they set out from Washington, D.C., to Wisconsin, about what they try to collect and why. Now that they’re at the event, curators Claire Jerry and Jon Grinspan reported back to Schalit on their collecting progress. Turns out, a clear plastic bag handed out to attendees may tell the big story of the convention, which began just a few days after the attempted assassination of former President Donald Trump.

GOP 2024 Convention attendees use clear plastic tote bags, usually with convention-related names or terms.

AP Photo/Jae C. Hong

Schalit: What are you seeing and what do you have?

Grinspan: There’s not a ton of handmade stuff, because the security perimeter is so tight. There’s not a lot of the kind of hats, the posters that we usually see. So there are fewer objects, in general, to collect.

Jerry: All of the delegates appear to have been issued clear plastic tote bags by their delegations. Some of them just say “RNC.” Some have a state name on them. Those were clearly designed well before the events of Saturday. So the clear plastic is a long-standing security measure.

Items collected at the GOP Convention by Smithsonian political history curators. Photo: Jon Grinspan, Smithsonian

Grinspan: Sometimes it’s frustrating not to come home with lots of things. Due to security concerns stemming from the assassination attempt, people have brought in fewer objects. At the same time, because this convention is so united behind Trump, there’s less need to use signs and other materials to object to or support other candidates. An absence of objects can say as much about a moment in time as a wealth of them.

We’re seeing a lot of MAGA hats with different themes on them. We collected one from an African American pastor from Virginia that says “MAGA BLACK” on it. There are tons of “45/47” hats, “ULTRA MAGA” hats, all these kind of things that have been distributed.

We’re handing out lots of business cards. A lot of times you meet people and hand out a business card because they have a cool object. You don’t know if you’ll get it, then maybe four weeks later, somebody emails you, and that’s how we get a lot of the objects in our collection. There are things that aren’t in our hands right now, but we hope we can collect.

What are some of the things you have in hand right now?

Jerry: We’ve gotten all of the signs that have been distributed to delegates on the floor, and we’ve been able to track when they were distributed, with an eye toward what speaker event officials were hoping people would hold them up for. So for example, the “Back the Blue” signs that came out last night were distributed right before a couple of speakers who were going to speak specifically about law enforcement issues, or were themselves law enforcement people.

These signs are interesting, because they tell you a lot about how the convention itself intends to be organized.

So you’ve got placards and signs that organizers are hoping will be used when somebody up on stage says something they know is coming because it’s scripted?

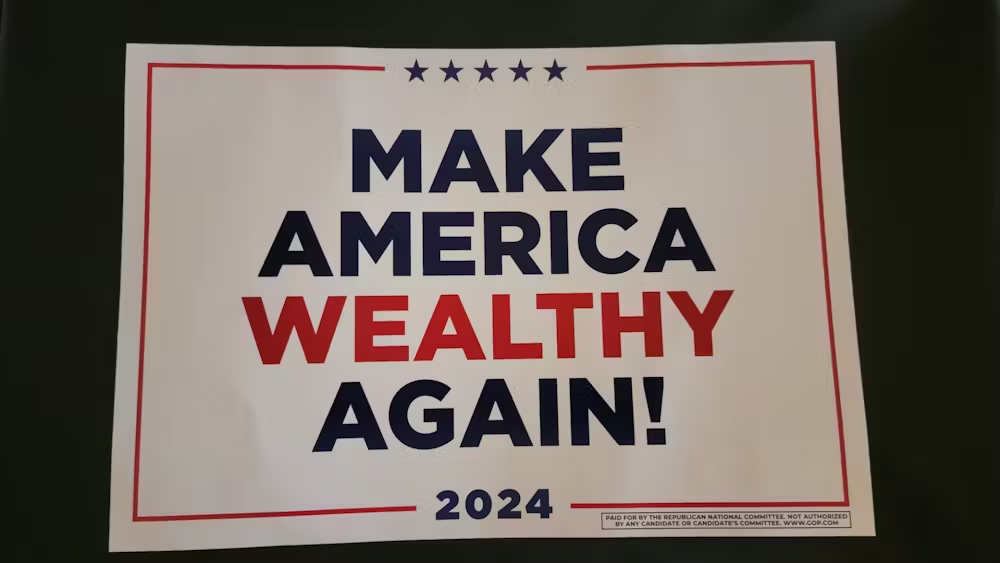

Jerry: That’s very, very typical for a convention. So, in this particular convention, as in many of them, they have a theme every night. The first night’s theme was about wealth and the nation’s economy. And so the signs said, “MAKE AMERICA WEALTHY AGAIN!” The theme the next night was safety. So the sign was, “MAKE AMERICA SAFE AGAIN!”

One thing that was interesting: convention volunteers will go around and put signs on seats. So when delegates get there, or audience members get there, there are signs available. When I first got my seat yesterday, the signs around me on the seats were the same “TRUMP” signs from the day before, in red, white and blue. And before yesterday’s events started, the “TRUMP/VANCE” signs had arrived. Sign teams were going around and picking up the signs that just had the one name and replacing them with signs that had two.

A sign from the GOP convention in Milwaukee, collected by Smithsonian curators. Photo by Claire Jerry, Smithsonian

Are there some interesting things that you’ve seen that would not fit into the collection?

Grinspan: We literally have a physical collection of campaign ephemera. We’re thinking about what we can fit, what we can store, what we can hold for 100, for 200 years. So we want to take home every shirt and every hat, but at some point, the question becomes, what is the additional value of maintaining this object over time versus something else?

Jerry: I’ve seen from a distance some articles of clothing – things that sparkle or glitter. I hope to get closer to those delegates today to see what their story is and how attached to the clothing they are, whether they’d be willing to share it. Sometimes we need to look at what the materials are that things are made out of, because there are some things that we just know either aren’t going to last or, sometimes with clothing that’s made for entertainment purposes, the material itself can be damaging to things around it because it off-gasses.

Grinspan: There’s a protest sign from the protest the first day that says, “STOP TRUMP AND RACIST REPUBLICANS.” As I mentioned earlier, this “MAGA BLACK” hat that was made by an African American pastor in Virginia tells an important story. And then there’s a kippah – a skullcap worn by some Jewish men – that says “TRUMP” on the front and “Republican Jewish Coalition” on the back. A kippah exactly like it was worn by a speaker last night.![]()

Claire Jerry, Curator in the Division of Political History at the National Museum of American History.

Claire Jerry is a curator in the Division of Political History at the National Museum of American History where she specializes in political rhetoric, the material culture of 20th- and 21st-century campaigning, and the history of the presidency. She has curatorial responsibility for the exhibit The American Presidency: A Glorious Burden and was team lead for the 2020 digital project #votehistory which focused on campaign rhetoric.

Jerry’s previous exhibits include serving as co-curator on the NMAH exhibit Elephants and Us: Considering Extinction and curator of From South Carolina to the World: Jimmy Byrnes and Political History (McKissick Museum), USC Goes to GTMO (McKissick), Tracing the Trumans: An American Story (Harry S. Truman Library and Museum), Moving Mountains: U.S. Presidents and the Panama Canal (Kansas City Public Library Truman Forum), and Paul Findley: A Congressional Office (Illinois College). Her work appears in The Smithsonian Book of Presidential Quotations (Smithsonian Books, 2024) and Smithsonian American Women: Remarkable Objects and Stories of Strength, Ingenuity, and Vision from the National Collections (Smithsonian Books, 2019). Her current research focuses on the intersection of rhetoric and material culture. Prior to entering the museum field, Jerry served as Chair of the Department of History at MacMurray College.

Jon Grinspan, Political History Curator

Jon Grinspan is a curator of political history and the National Museum of American History. I study the deep history of American democracy, especially the wild partisan campaigns of the 1800s. At the same time, I collect objects from contemporary protests, conventions, elections, and riots for the Smithsonian, to try to preserve our own heated moment for generations to come. Together, it involves a bit of time-traveling, explaining the past to the present, and the present to the future.

My first book, The Virgin Vote: How Young Americans Made Democracy Social, Politics Personal, and Voting Popular in the Nineteenth Century uncovered the forgotten history of the youth vote, to show that young men and women were once the most engaged, and sought after, demographic in American politics.

My new book, The Age of Acrimony: How Americans Fought to Fix Their Democracy, 1865-1915, chronicles the way that the “normal” democracy we inherited from the 20th century was invented, around 1900, to restrain the vibrant but violent partisan political campaigns of 19th century America. To tell this story, The Age of Acrimony follows the father-daughter political dynasty of radical congressman William “Pig Iron” Kelley and his labor activist daughter Florence Kelley.

Welcome to The Conversation. The Conversation U.S. is an independent, non-profit news organization that publishes evidence-based, explanatory articles written by scholars, edited by experienced journalists and delivered directly to the public in plain English.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Learn more on The Conversation’s website and see a full list of articles written and published by Smithsonian scholars.