Thousands of Republicans, from a presidential candidate to grassroots party members, began assembling in Milwaukee on July 15, 2024, for that quadrennial political ritual, the party convention. Political history curators from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History were there, too. They’re self-described “scavengers” of the physical objects that make up political campaign history, from candidate buttons to signs, banners and anything else that can enter the Smithsonian’s campaign collection – which dates back to George Washington – in order to “make sense of our moment to people wondering what we were all thinking,” as curator Jon Grinspan put it. Grinspan was joined by curators Claire Jerry and Lisa Kathleen Graddy in an interview with The Conversation’s politics editor, Naomi Schalit. They will report back to Conversation readers during the convention about their progress.

Schalit: What do political history curators do?

Lisa Kathleen Graddy: We try to document, through material culture, Americans’ relationship with their democracy, with their government, how they are affected by it, how they affect it, and how they interact with it. Material culture is all of the ephemera and the products that people make and use to express their opinions about politics.

Claire Jerry: We go into the field so we can watch people in real time working and interacting with these objects. But we also want to place that in a historical context. Obviously none of us were able to watch anyone do that in 1860 or 1896, but by watching how people do it today, we can go back and reinterpret the objects that we collected from the past.

Jon Grinspan: We try to explain the past to the present and the present to the future. We’re trying to draw from our really broad, deep history of democracy to make some sense of the present.

What are some notable items in your collection?

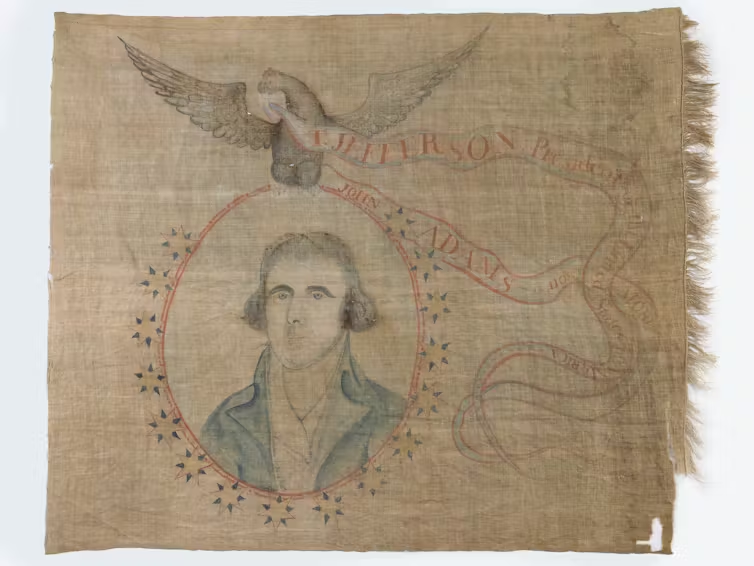

Graddy: One of my favorite objects is a banner from Thomas Jefferson’s 1801 inauguration. It has a portrait of Thomas Jefferson, and an eagle is holding one of two ribbons above his head. And the ribbons say, “T. Jefferson, President of the United States, John Adams is no more.”

A cloth banner celebrates the electoral victory of Thomas Jefferson over John Adams in the presidential election of 1800. Smithsonian National Museum of American History

The election of 1800 was an ugly, bitterly fought election that tore apart two friends – Jefferson and Adams – and pitted parties against each other. But it’s also one of the moments when we knew democracy would work. The losing side left, the winning side came in, and the response was, we’ll meet you again in four years and we’ll try it again. It’s one of the things that I look at that reminds me that we’ve been in bad places before, and we’ve worked through them.

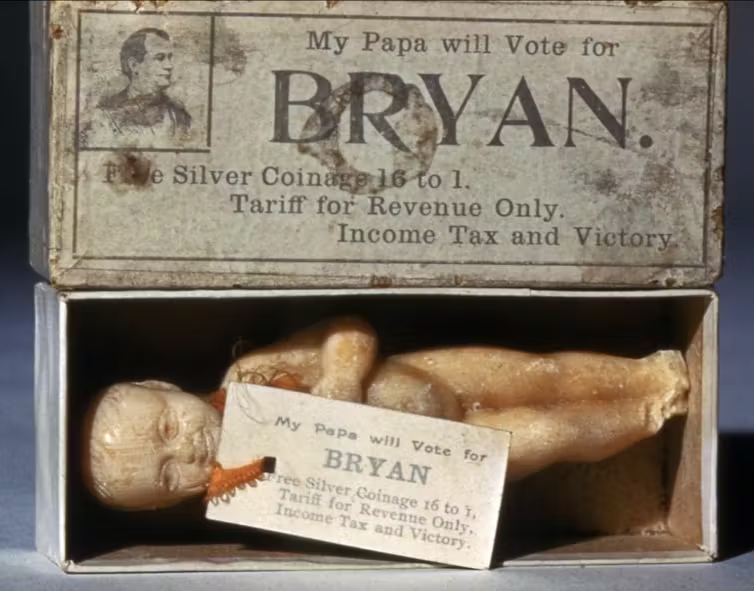

Jerry: I often follow Lisa Kathleen telling that beautiful story and warming everybody’s hearts by telling stories about the more ridiculous and goofy things that happen in campaigns. And one of my favorite objects in the museum is the 1896 soap babies.

They are 4-inch-long infants shaped out of soap that were produced by soap companies to promote both William McKinley, the Republican nominee, and William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic nominee. They came in little boxes with tags that said, “My pa’s for free silver! My dad will vote the gold standard!” Because, of course, nothing says economic policy like a 4-inch naked baby made out of soap. They of course had nothing to do with economic policy. Voters apparently hated them because they thought they looked too much like babies in coffins.

Made for the 1896 campaign of William Jennings Bryan, this infant-shaped soap in a cardboard box has a tag promoting the policies of Bryan’s Democratic Party. Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Ralph E. Becker Collection of Political Americana

But I like to talk about them because I love to talk about how technology has influenced what we collect over the years and what we use in campaigns. This was all about soap manufacturers saying, look at the new, cool things we can make out of soap.

Grinspan: We have two blue umbrellas. One is kind of a demure 1950s umbrella from Dwight Eisenhower’s campaign that says, “I like Ike” all over. And we have a blue umbrella from the 2016 campaign, used by Bernie Sanders protesters outside of the Democratic convention. It has Sanders’ name scrawled all over it. It’s really loud in just the writing. And even if you didn’t know how to read, even if you didn’t know who Eisenhower and Sanders were, these objects speak materially to tell you something about their era.

What are you going to look for at the convention?

Grinspan: Obviously we’re going to look for materials about a former president who’s running for the second time, about the relationship between the campaign and the party, and the party and the grassroots or anonymous campaigners. But I really don’t think it’s a good idea to go out there with a checklist. A lot of collecting is spontaneous. You see an object that just captures a moment or expresses something really striking or speaks to other items in our collection in a way that is ineffable or beyond words.

How do you go about collecting when you’re at one of these events?

Graddy: We scavenge. We trawl through the place and pick things up, from signs that are left to signs they’re handing out. But we are also, um, extremely polite. I don’t want to say we’re stalkers, but we observe people. We spot the thing that we think we’re interested in and we walk up ever so nicely with a handshake and a business card and say, “Hi, I’m Lisa Kathleen Graddy. I’m a curator at the Smithsonian Institution. I really like your hat. Would you like to talk about maybe becoming a part of the national narrative at the museum on the Mall?”

What’s the craziest thing you’ve had to carry back from a political event?

Graddy: The standards at conventions, the big columnlike signs that give the state’s name, are very popular souvenirs. Convention organizers assume they will go missing throughout the convention, and they have more of them. We frequently try to get the standard of the candidate’s state. We were very lucky that, while there was no getting the New York standard at the Republican convention in 2016, Jon and I talked to the delegations from Indiana and Colorado who decided that they would hold on to theirs and guard them for us.

The last night of the convention, the delegations all signed them and Jon and I walked out of the convention with two standards. Heading to our car, they were getting a little heavy, so we actually got into a pedicab. Somewhere in the world there are cellphone pictures of us sitting in a pedicab with these two delegation standards, driving down the road in Cleveland.

Claire, you recently went to the Libertarian convention. What did you find there?

The porcupine became the official mascot of the Libertarian Party in 2020. This button was given away at the 2024 Libertarian National Convention in Washington, D.C. Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Jerry: The Libertarian convention felt much more like a historic convention, in the sense that they don’t have a candidate already designated, and they also don’t run as a team, so you have separate groups of people running for vice president and president. All of those candidates have tables in a vendor area with buttons and flyers and books they’ve written and lanyards, all of which I picked up. One of the things we do is pick up what’s available to anybody who’s attending the convention.

I was interested to see that the Libertarians have an official symbol, which is a very elegant torch. But they also have an animal. We are all accustomed to red, white and blue elephants and donkeys. I was less accustomed to yellow and gold porcupines, which is the Libertarian symbol. Seeing people wearing porcupine-themed clothing and handing out porcupine buttons was a lot of fun.![]()

Welcome to The Conversation. The Conversation U.S. is an independent, non-profit news organization that publishes evidence-based, explanatory articles written by scholars, edited by experienced journalists and delivered directly to the public in plain English.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Learn more on The Conversation’s website and see a full list of articles written and published by Smithsonian scholars.

Naomi Schalit, Senior Editor, Politics + Democracy, The Conversation

Jon Grinspan studies the deep history of American democracy, especially the wild partisan campaigns of the 1800s. At the same time, he collects objects from contemporary protests, conventions, elections, and riots for the Smithsonian, to try to preserve our own heated moment for generations to come. Together, it involves a bit of time-traveling, explaining the past to the present, and the present to the future.

His first book, The Virgin Vote: How Young Americans Made Democracy Social, Politics Personal, and Voting Popular in the Nineteenth Century, uncovered the forgotten history of the youth vote, to show that young men and women were once the most engaged, and sought after, demographic in American politics.

His new book, The Age of Acrimony: How Americans Fought to Fix Their Democracy, 1865-1915, chronicles the way that the “normal” democracy we inherited from the 20th century was invented, around 1900, to restrain the vibrant but violent partisan political campaigns of 19th century America. To tell this story, The Age of Acrimony follows the father-daughter political dynasty of radical congressman William “Pig Iron” Kelley and his labor activist daughter Florence Kelley.

Lisa Kathleen Graddy is a curator of American political history, reform movements, and women’s political history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Her work and research centers on the ways that Americans, particularly women, have found a public voice and wielded political power through organizing, participating in, and building institutions such as reform movements, voting rights movements, suffrage organizations, and political parties.

Lisa Kathleen Graddy is a curator of American political history, reform movements, and women’s political history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Her work and research centers on the ways that Americans, particularly women, have found a public voice and wielded political power through organizing, participating in, and building institutions such as reform movements, voting rights movements, suffrage organizations, and political parties.

Graddy’s recent work includes curating the museum’s exhibition, Creating Icons: How We Remember Woman Suffrage, for the 100th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment and the exhibition, American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith (co-curator). She is also the curator of the museum’s popular ongoing exhibition, The First Ladies. Her past work includes the exhibitions Votes and Voices: Democracy in America (co-curator); Hooray for Politics (co-curator); The National Woman Suffrage Parade, 1913; A Letter from George Washington, November 30, 1785 (co-curator); The First Ladies; A First Lady’s Debut; The First Ladies at the Smithsonian; and Exhibiting George Washington.

Graddy is a co-author of American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith (Smithsonian Books, 2017), a companion book to the museum’s exhibition and The Smithsonian First Ladies Collection (Smithsonian Books, 2014). Her writing is featured in Smithsonian American Women: Remarkable Objects and Stories of Strength, Ingenuity, and Vision from the National Collections (Smithsonian Books, 2019) and Smithsonian Civil War: Inside the National Collection (Smithsonian Books, 2013). She can be seen talking about voting and women in political life in programs like She the People: Votes for Women (Smithsonian Channel, 2020).

After spending the last few years working on exhibits and programs to mark the 100th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment, Lisa Kathleen is continuing to research and expand the collections documenting women in modern American political life.

Claire Jerry is a curator in the Division of Political History at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.