An author for the ages

“A writer is by definition a disturber of the peace”

James A. Baldwin

August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987

Author and civil rights activist James Arthur Baldwin (born James Arthur Jones) was celebrated during his lifetime for his essays, novels, plays, and poems as well as his profound influence on the culture of his—and our—time. The eldest of nine children, he was born into a family struggling to rise above poverty. As a teenager, he followed his stern stepfather into the clergy, but he quickly broke away from the pulpit to pursue a passion for writing. Those early years engulfed in poverty and religion would influence Baldwin’s work for life, even as they took him far from the streets that forged him.

His 1953 novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, has been recognized as among the top 100 novels in the English language while the 1955 essay collection, Notes of a Native Son, established him as a prominent voice for human equality.

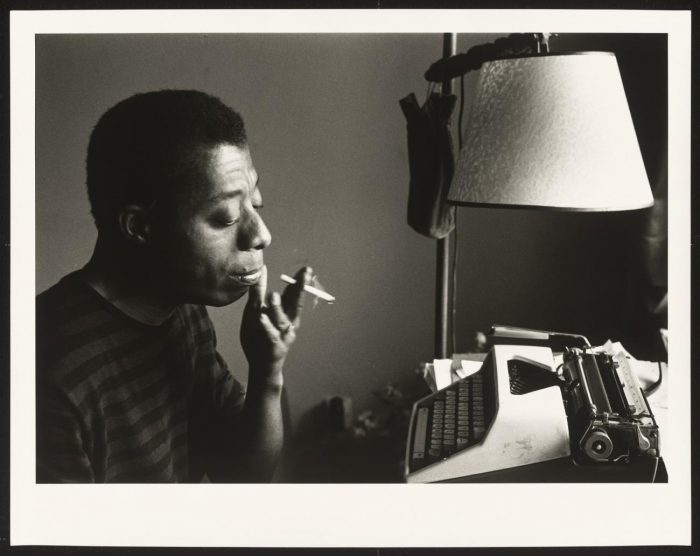

James Baldwin at his typewriter, Istanbul 1966.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, © Sedat Pakay 1966

Baldwin’s literary works explored deep personal questions and dilemmas within the context of complex social and psychological pressures. His narratives often intertwined themes of masculinity, sexuality, race, and class, influencing both the civil rights and gay liberation movements in mid-20th century America. His protagonists, often African American and frequently gay or bisexual men, faced both internal and external challenges in their quests for self- and social acceptance, as exemplified in his 1956 novel Giovanni’s Room.

This Morning, This Evening, So Soon: James Baldwin and the Voices of Queer Resistance

In 1948, when Baldwin was 24 years old, he left New York for Paris. He knew no French and had only 40 dollars to his name. But the burgeoning novelist, essayist, and playwright felt he had to leave America to free himself from the racism that conspired to hinder his growth as an artist. In France, Baldwin created a kind of extended family that included the American painter Beauford Delaney and the musician Nina Simone—artists who, not unlike Baldwin, had survived poverty, segregation, and homophobia to become significant figures on the world stage.

After nearly a decade in Paris, Baldwin felt compelled to return to the United States. In 1957, he caught a glimpse of a picture of Dorothy Counts facing a hostile white crowd as she made her way to integrate a high school in North Carolina. “The photo made me furious,” Baldwin recalled. “Everybody else was paying their dues, and it was time I went home and paid mine.”

Back home, Baldwin wrote, marched, and made speeches while supporting the work of activist friends and associates, such as Lorraine Hansberry and Bayard Rustin—queer thinkers who, despite their exceptional rhetoric, were not out during the civil rights movement; the general feeling was that their difference would undermine the cause.

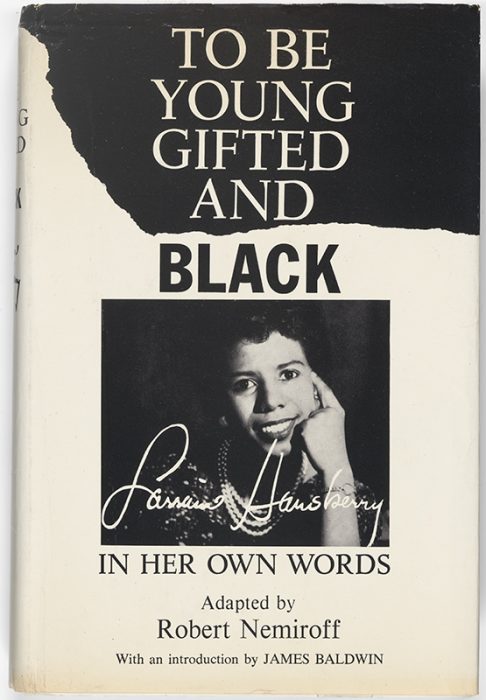

o Be Young, Gifted and Black: Lorraine Hansberry in Her Own Words

With an introduction by James Baldwin and original art by Lorraine Hansberry, this memoir incorporates Hansberry’s perspectives on gender and racial equality, family, and politics. Originally an off-Broadway play created and developed by Hansberry’s ex-husband, Robert Nemiroff, the book comprises interviews, letters, and journal entries that paint a layered portrait of a young artist and activist. As the first Black woman to have a play produced on Broadway, with A Raisin in the Sun (1959), Hansberry’s autobiography embodies her motivations and work: to be young, gifted, and Black. Hansberry’s dear friend Nina Simone, who is presented nearby, penned a song with this title.

Toward the end of his life, Baldwin talked about his sexuality more openly, but it was his strong desire to always “bear witness” during troubled times, in troubled lands, that helped inspire the late Congresswoman Barbara Jordan, poets Essex Hemphill and Marlon Riggs, and many other intellectuals.

This Morning, This Evening, So Soon: James Baldwin and the Voices of Queer Resistance, which takes part of its title from a short story Baldwin published in The Atlantic in 1960, is on view at the National Portrait Gallery through April 20, 2025. The exhibition is a reckoning of sorts—an homage to Black queer force as it continues to live and feed this nation’s activist spirit.

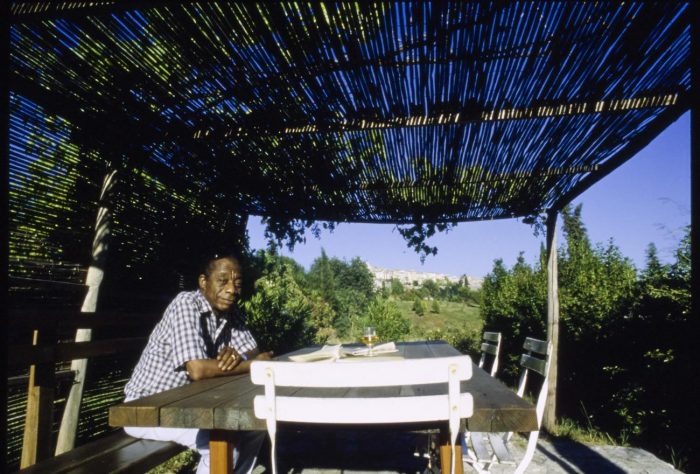

The power of place

Chez Baldwin, an online exhibition from the National Museum of African American History and Culture, is an exploration of James Baldwin’s life in St. Paul de Vence, France.

James Baldwin, Architectural Digest © Condé Nast

“Once I found myself on the other side of the ocean, I could see where I came from very clear … You can never escape that. I am the grandson of a slave, and I am a writer. I must deal with both.”

— James Baldwin

Toward the end of his life, Baldwin talked about his sexuality more openly, but it was his strong desire to always “bear witness” during troubled times, in troubled lands, that helped inspire the late Congresswoman Barbara Jordan, poets Essex Hemphill and Marlon Riggs, and many other intellectuals.

A photograph of James Baldwin and friends seated at the “welcome table” outside his home in the South of France.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of The Baldwin Family

“Chez Baldwin,” Baldwin’s home in the south of France, serves as a powerful lens to explore his life and works. From 1971 to 1987, the last 16 years of his life, his home in France was his permanent abode and an important social center for artists and intellectuals from Europe, Africa, America, and around the world.

History can be a weapon in the fight for freedom and justice

“As we celebrate his 100th birthday, James Baldwin’s wisdom is as salient today as it was during his lifetime. What happened long ago continues to reverberate, shaping our current reality. The legacies of slavery and Jim Crow are still made manifest in the systemic racism and social inequities preventing us from reaching our full potential as a nation. And yet, we are told that we need not learn about that history, that our children should not read about it in their school libraries, that they should be shielded from knowing about ugly truths lest carefully constructed myths be scrutinized, questioned, and discarded…. To me, [Baldwin] was the embodiment of the truths that history can be a weapon in the fight for equality and freedom, and that there is nothing more powerful than a people, than a nation, steeped in its history. As we celebrate his birthday and the legacy he left us, I hope we heed his advice and honestly interrogate our history so we can secure a brighter shared future.”

—Lonnie G. Bunch III

Excerpted from the 10th anniversary volume of James Baldwin Review, to be released in October 2024

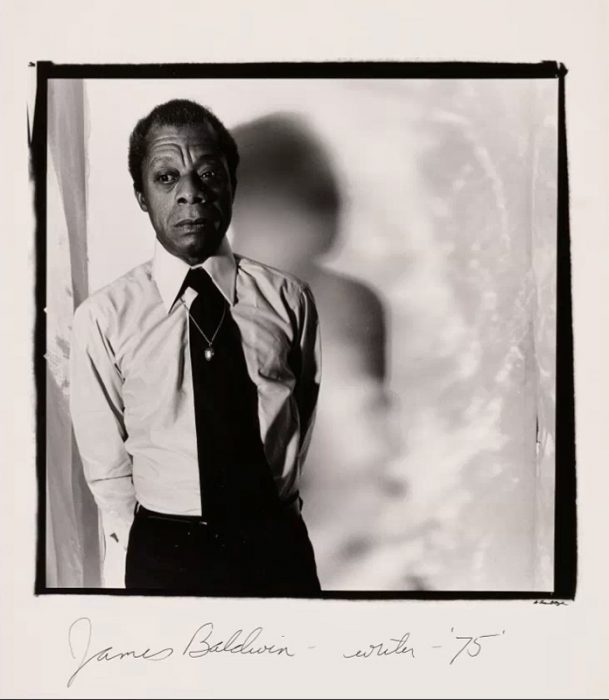

James Baldwin, writer. 1975

Anthony Barboza (born 1944) / Reproduction of gelatin silver print from 1975 / Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; gift of the Loewentheil Family

Posted: 2 August 2024