Conserving Culture and Producing Posies

For four decades, senior objects conservator Carol Grissom has coaxed museum pieces to give up their secrets.

From Neolithic statues excavated in Jordan to an 19th-century English door lock found on the grounds of the Environmental Research Center in Edgewater, Md., Grissom has analyzed and treated artifacts around the globe.

With her retirement from SI’s Museum Conservation Institute taking effect within months, the Torch asked Grissom to reflect on her career, whose trajectory was shaped in part by field trips to Boston museums back when she was earning her bachelor’s degree in art history at Wellesley College, Wellesley, Mass.

During her senior year, In a course that explored different possibilities for working in a museum, “paper conservators at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts spoke about their work, and it was like a light bulb coming on,” Grissom says. “I knew I liked working with my hands. I liked art history, too, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to be an art historian:” too much time spent looking at pictures on a page. The tactile pleasures of being able to interact with the objects held enormous appeal, she says.

The path forward became clear after Grissom had matriculated at the University of Chicago’s doctoral program in art history. She spotted an ad for a conservation program at Oberlin College, applied to it and was accepted, ultimately earning her master’s in conservation.

“When I was at Oberlin, my professors were all in their 70s and still interested in the profession,” she says. “I thought that was a good sign!”

The Nebraska native’s pivot paid off.

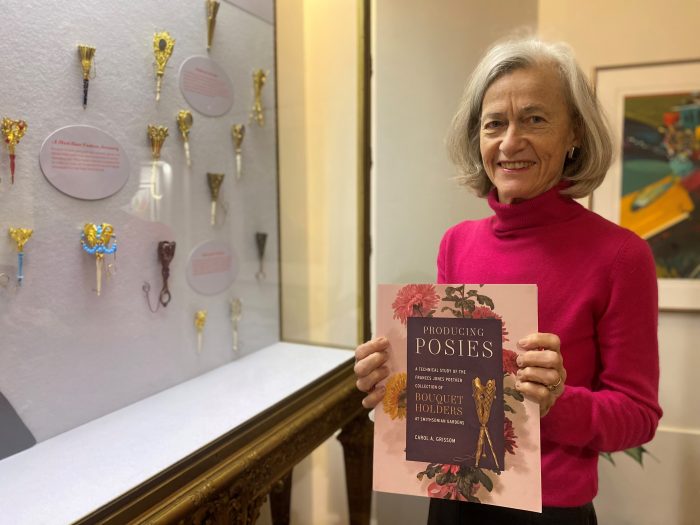

Carol Grissom with her latest book next to a display of some of the restored Victorian bouquet holders featured in “Producing Posies.” (Photo by Amy Rogers Nazarov)

“One of the pleasures of being a conservator is you actually get to touch the items,” she says. She mentions a recent news story about a child who accidentally broke a 3,500-year-old vase at Haifa, Israel’s Hecht Museum. Grissom was unfazed by the story (“I expect it was already partly broken”), adding she could relate to that curious youngster.

Other aspects of objects conservation Grissom has enjoyed: the satisfaction of taking practical steps to repair and salvage an artifact for future viewers, and the layers of history an object may reveal along the way.

“Carol has been a significant voice for tying technical research and conservation together for the SI and for the field,” says Jessica Johnson, head of conservation at MCI and Grissom’s supervisor.

Across SI, exhibitions typically dictate where conservators focus their attention, Johnson says. “There’s so much work taking care of collections and objects that there is not a lot of time to do deep research,” she observes. Yet it’s just that kind of research where Grissom excels.

Grissom’s work cleaning hundreds of 19th century bouquet holders evolved into “a deep historical study,” Johnson says (see box below). “I have never known anyone in our field who has been so effective at tracking down information” that helps us deepen our understanding of objects’ cultural significance, Johnson adds.

After completing her master’s degree at Oberlin, Grissom received further training at the national conservation institutes of Belgium and Italy. Then, following the 6.5 magnitude Friuli earthquake, which occurred on May 6, 1976, she helped restore frescoes, statuary and other damaged works.

“An American group paid me about $20 a day,” she recalls. For $3 a day, “I lived in a building that once housed young men entering the priesthood.” And the frigid weather meant that typically Grissom would get out of bed, get dressed – in long underwear, overalls, several sweaters, jacket, hat, scarf, and leather gloves thin enough to allow her to grasp a pen and make notes – then get to work in the unheated, deconsecrated church that had been converted to a storehouse for the damaged items.

“The woman who was in charge of the facility would lock me in,” Grissom laughs. “At 1 p.m., she would come back and let me out.

“I surveyed artifacts that had been brought from small churches in the Dolomites after the earthquake,” trying to ascertain which could be benefit from immediate treatment, akin to triaging victims of a car crash.

Grissom describes the process she used. “I would take a photo of the object, often a polychrome painted wooden statue, then write down the materials used and a short description” of what it was. Gathering this information “helps you understand what is going on with the object and how urgent treatment is” Something that was broken or deemed likely to deteriorate further would typically garner more attention than something merely chipped.

After returning to the US, Grissom held positions working on outdoor sculptures at Washington University in St Louis and in exhibit conservation at the National Gallery of Art before starting at what was then known as the Conservation Analytical Lab (CAL) on April 15, 1984, just after it had moved from the American History Museum to MSC. CAL morphed into the Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education, which became MCI in 2006.

Through these name changes, Grissom’s commitment to mentoring newcomers to the field has never wavered.

“Carol has generously shared her knowledge with the many conservation students and fellows she has mentored over her career, many of whom have gone on to become leaders in our field,” says Sanchita Balachandran, director of MCI. “She is well known for her no-nonsense pragmatism, her absolute dedication to her work, and her sharp and perceptive eye for those sometimes small but critical details in cultural heritage objects that open up avenues for other scholarly inquiry.”

Looking back over her long career, Grissom says she wouldn’t change a thing.

“There are always new objects to examine and new problems to solve,” she says. “I am really going to miss it.”

A selection of Victorian bouquet holders on display in the Ripley Center. (Photo by Amy Rogers Nazarov)

Posted: 12 November 2024

- Categories:

nice writing & good photography!

Thank you, Mary!