There they are. Together. On the threshold of two rooms and history.

Official Washington at the time, however, was no picnic and the White House no palace. Only two days before the portrait session, Iranian students had stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and taken dozens of Americans hostage. Jimmy Carter was reportedly relaxed when he posed for the picture, so presumably he was feeling hopeful that diplomacy would end the crisis, unaware that it would take 444 days for the captives to be freed. With his innate sense of creating history, Carter’s successor, Ronald Reagan, would orchestrate the return of the hostages on the day of his inauguration, and Nancy Reagan, wearing a dress very similar to Rosalynn Carter’s, would claim ownership of “Reagan red.”

President Jimmy Carter and first lady Rosalynn Carter at the White House on Nov. 6, 1979. (Ansel Adams/National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Mr. and Mrs. James Earl Carter Jr.)

No one quite knows who chose Adams to shoot the Carters’ portrait, but the consensus is that it was Joan Mondale, the wife of the vice president, who was also a commissioner of the National Portrait Gallery. It was an unusual choice because Adams was a famous landscape photographer, better known for black-and-white stills of the American West. Taking pictures of famous people was not really his forte. However, when Mary Ann Tighe, the deputy chair of the National Endowment for the Arts and an adviser to the vice president, asked Adams to accept the commission, he considered it a great honor. “It was, indeed, one of the most significant experiences of my life,” he wrote to the president two days after the portrait session.

Ansel Adams photographing President Jimmy Carter using Polaroid’s giant 20×24 camera on Nov. 6, 1979. (Courtesy of the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

Mondale might have approached Adams also because, in customary fashion, Jimmy Carter wanted to save money. A photograph was cheaper than a painting, and to make it even more palatable, Adams waived his fee, asking only to have the expenses for a five-day trip and two assistants covered. Adams also secured the cooperation of Polaroid Corp. to make its new 20×24 camera available at no cost. As tall as the photographer himself and weighing in at more than 200 pounds, the camera was a huge and cumbersome piece of equipment that might have been impractical to lug over mountains but was suitably impressive to take to the White House, especially when Polaroid provided technicians to help. Even more excitingly, it offered, like all Polaroid technology of that era, unique and immediate results, because all the chemicals needed to develop a single 20-by-24-inch picture in 60 seconds were built into it. Afterward — setting all frugality aside — Adams felt he had made the first couple “look like a million dollars.” He also took a series of smaller Polaroids — the famous 3-by-3-inch color prints that by 1977 had captured two-thirds of the instant camera market — as well as a number of shots with his trusty 4×5 Horseman and Hasselblad 500C cameras in case something should go wrong.

Adams made several portraits between Nov. 5 and 6, including one at the Naval Observatory of Vice President Walter Mondale (who, when he saw the size of the Polaroid 20×24, quipped, “Well, I guess this is a big enough camera to capture the egos in this town”) and one of Carter alone in the President’s Dining Room of the White House. Reflecting his passion for the environment, however, Adams managed to include the historical French landscape wallpaper as Carter’s backdrop. He also had him stand on a box to gain height against the decorative mantelpiece. “At one point I was not succeeding verbally in correctly [placing] the President, so I walked up to him and gently pressed his shoulders into a more agreeable angle to the camera,” Adams recalled in his 1985 autobiography. “Suddenly, a firm, stern hand rested on my shoulder; I did not realize that it is taboo to touch the President, and the Secret Service man was very alert. … It was cause for genial laughter from all.”

Posing Carter against a landscape backdrop might also have primed the president for the conversation that Adams, an ardent conservationist and member of the Sierra Club, really wanted to have, about the need for the government to take the lead on protecting the environment. Adams pressed his case in his letter penned two days after the session. He expressed appreciation for Carter’s “incredibly bold actions” on enlarging designated wilderness areas in Alaska but confessed “impatience” that more wasn’t being done. Carter, who had already installed solar panels on the White House and urged Americans to turn down their thermostats, replied the following day to say he had shown Adams’s letter to his staff, who collectively affirmed the importance of preserving wilderness areas for future generations. “All of us consider the protection of Alaskan lands the top environmental issue of our time,” he hand-wrote in gratitude and admiration to his “friend and partner.”

Keeping true to his commitment, as a parting gesture to the nation after losing reelection, Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act on Dec. 2, 1980, protecting more than 157 million acres of federal land from large-scale commercial logging and mining in an area larger than California. This was — and remains — the largest expansion of protected lands in U.S. history and doubled the acreage of the National Park System.

When Adams met the Carters, he presented them with his latest book, “Yosemite and the Range of Light,” and an original photograph of Mount McKinley and Wonder Lake. The Carters, in turn, invited him and his family to Thanksgiving in Georgia — an honor Adams had to politely decline because of other plans. Nevertheless, a friendship developed, and on June 9, 1980, Carter awarded Adams the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Curiously, although the portrait of the Carters had been intended for the National Portrait Gallery, it was gifted to the museum in 1980 by the Carters themselves. Adams had given it to them, and they donated it to us.

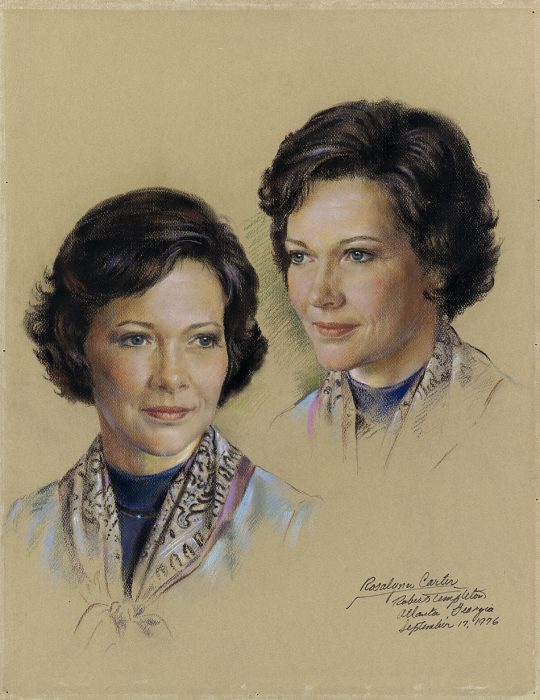

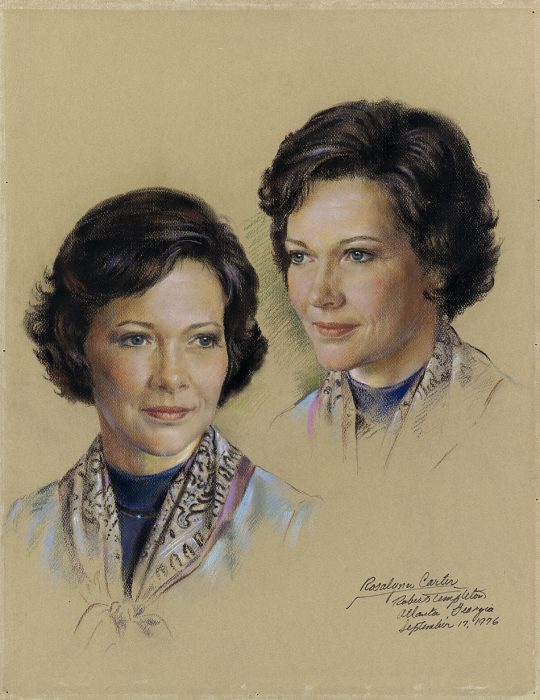

The story ends with a twist. Photographic prints, as you might know, are a fairly fragile medium that cannot be displayed in strong light or unstable humidity for long periods of time. So despite his best intentions, Jimmy Carter had to pose for an oil painting that could be placed on permanent view in the “America’s Presidents” gallery. Today, he can be seen standing full-length in the Oval Office as it looked in 1980. The artist was Robert Clark Templeton, whose sketches of the Carters had appeared in the February 1977 issue of Good Housekeeping magazine. The National Portrait Gallery acquired Templeton’s double-portrait pastel drawing of Rosalynn Carter in 2013.

This essay by Kim Sajet, director of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. has benefited from an excellent blog post by Daria Labinsky about the portrait sessions with Ansel Adams, written in 2020 on behalf of the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum.

This essay by Kim Sajet, director of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. has benefited from an excellent blog post by Daria Labinsky about the portrait sessions with Ansel Adams, written in 2020 on behalf of the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum.

Sajet’s essay was originally published by the Washington Post. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

Read more

Rosalynn Carter by Robert Clark Templeton / Pastel on illustration board, 1976 / Donated by Mark, Kevin, and Tim Templeton, sons of the artist / © 1976, Templeton Collection

In Memoriam: James Earl Carter

This essay by Kim Sajet, director of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. has benefited from

This essay by Kim Sajet, director of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. has benefited from

Gabrielle Obusek is the public affairs specialist for the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

Gabrielle Obusek is the public affairs specialist for the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.