From Shadow to Substance

A chance encounter and a new exhibition demonstrate the power of photography to “Secure the shadow, ere the substance fade.”

Shortly after the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, I was contacted by a local woman who said her godmother wanted to meet me because she “knew my family.” Though I normally abstain from responding to cryptic messages from strangers, I was intrigued. I gave her godmother a call and decided to go visit after learning more about this possible connection.

As we chatted in her home, my new acquaintance revealed that her mother and my paternal grandmother, Leanna Brodie Bunch, were best friends growing up in North Carolina. In 1909, Leanna moved to the North and left this woman’s mother a photograph, one that she still had and wanted to give to me. Prior to that moment, I had only ever seen my grandmother as a woman in her late seventies; she passed away when I was a toddler. When I first saw the photograph of my ancestor as a young woman, on the cusp of changing the course of our family’s history, I was moved to tears. Since then, I have been struck by the power of photography to teach us about who we are, and how we remember.

A new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, From Shadow to Substance: Grand-Scale Portraits During Photography’s Formative Years, explores the evolution of early photography and offers us a lens to view 19th-century American culture, both figuratively and literally. Opening June 20, the exhibition will be embedded in the “Out of Many” galleries on the first floor, which cover the beginnings of the nation to the end of the 1800s. The earlier sections are largely paintings, sculptures and prints, so these photographs offer a bridge to a new medium of portraiture.

After being introduced in France in 1839, daguerreotypes became the first photographic process to reach a U.S. commercial market. The least expensive whole-plate photographs—the “large” format of eight-and-a-half by six-and-a-half inches showcased in this exhibition—cost around fifteen dollars. While that may not sound like an extraordinarily high price in today’s dollars, lead curator Ann Shumard says that amount of money could have purchased a year’s supply of coal to heat a family’s home.

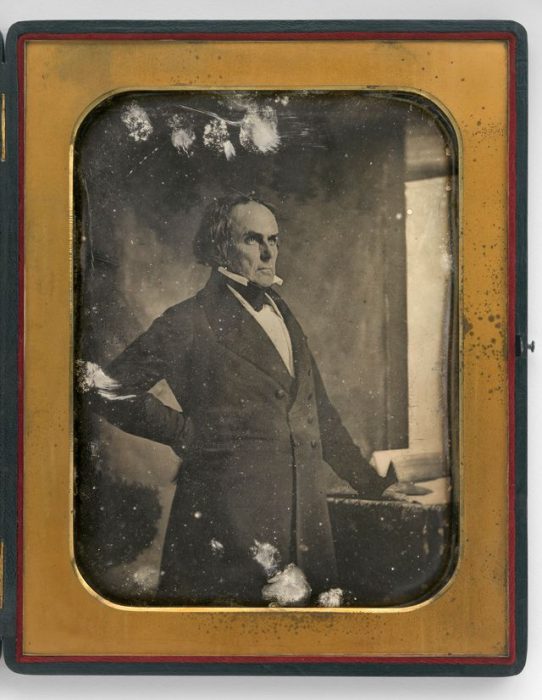

Daniel Webster by Southworth & Hawes, whole-plate daguerreotype, c. 1846. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; conservation made possible by a grant from the Smithsonian’s Collections Care and Preservation Fund.

Thus, it is unsurprising that the subjects of many whole-plated daguerreotypes in this collection are names many will recognize. The images of prominent political figures Daniel Webster and John C. Calhoun expose the tensions that later led to the Civil War. A portrait of Bostonians Isaac P. Davis and William Hickling Prescott reveals the prominence of philanthropy in public life at the time. A picture of Jonas Chickering, “the father of American piano making,” shows that we are not far removed from groundbreaking inventions we now take for granted. And the portrait of Lemuel Shaw, the judge who supported the constitutionality of the notorious Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, puts a face to the inhumanity of a court decision that destroyed countless lives and forever changed the country.

As the technology developed, photographers expanded their range of subjects. The ambrotype, which arrived in the U.S. around 1854, and the tintype, which was invented by a chemistry professor in Ohio in 1856, helped to democratize photography. A whole plate of a tintype was around 75 cents to a dollar, and it became possible to purchase smaller versions of all three types. Though undoubtedly an investment (the average daily wage in the 1860s was about two dollars), far more workers were able to capture images of their families and themselves. One remarkable tintype on view in From Shadow to Substance is of an unidentified African American woman dressed to the nines for her portrait. Her dignity and poise make a strong impression on the viewer. This woman’s sense of herself is clearly seen through the photographer’s lens. As James Baldwin wrote, “The language of the camera is the language of our dreams.”

Unidentified woman by unidentified artist, whole-plate tintype, c. 1865. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. This image has been edited to improve contrast and visibility.

Unlike an iPhone camera roll with fifteen glamour shots of last evening’s dinner, people traveled to studios perhaps once a year, or even just once in their lifetimes. Particularly renowned photography studios of the era include Southworth & Hawes in Boston and Brady’s Daguerrean Galleries in New York, both of which have advertisements highlighted in the exhibition.

Americans’ willingness to spend hard-earned money for formal portraits is captured by the exhibition’s title, a play on a famous slogan from photographers at the time: Secure the shadow (image or likeness), ere the substance fade (to have in the event of death or physical decline).

“You couldn’t know whether you were going to survive the next yellow fever epidemic, or if your child was going to live beyond infancy,” says Shumard. “The idea that you could actually have a picture made that could be a permanent representation of that person was tremendously appealing.” Smaller tintypes were also more durable, so Civil War soldiers could carry photos of their families on the battlefield or offer photos of themselves to their loved ones, just in case.

That many of those photos survived, some of which the Smithsonian is fortunate to hold in our collection, amazes me. They allow us to piece together our pasts and create connections within history and across art that are only possible to see now. The National Portrait Gallery has paintings of Calhoun and Webster, and the adjoining Smithsonian American Art Museum houses landscapes by John Frederick Kensett, whose ambrotype portrait will be in this exhibition. Without these photographs, says Shumard, “you have the art, but you don’t have the person behind it.”

We may already understand someone to be a part of our family or a part of our country’s history. But the Smithsonian can give us the tools to see them in a whole new light.

Posted: 2 June 2025

-

Categories:

Art and Design , Education, Access & Outreach , From the Secretary , Portrait Gallery