On the road in Arizona: The Secretary’s travel journal

(Image via galiuros)

March 7, 2011—Tucson, Arizona

The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory is a far-flung enterprise. Having grown beyond the capacity of its original location on the National Mall, in 1955 the Observatory moved its headquarters to Cambridge, Mass., to create the Center for Astrophysics, a joint program with Harvard University. It has been my pleasure to visit SAO in Cambridge a number of times and each time to be impressed by the Observatory’s leadership in astrophysical and astronomical research and its commitment to share that work through educational outreach. Today, SAO operates, solely or in partnership, facilities in Arizona, Hawaii, Chile, the South Pole and outer space. I have visited the sites in Chile and the South Pole—locations with special conditions that allow astronomical observations that cannot be obtained elsewhere. On this trip I look forward to seeing the SAO’s famed Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory on top of Mt. Hopkins, south of Tucson, Arizona. One of my goals in the future is to also visit the SAO facilities in Hawaii, but I suspect that any visit to the telescopes in outer space will have to wait for a cheaper form of space travel than we have now.

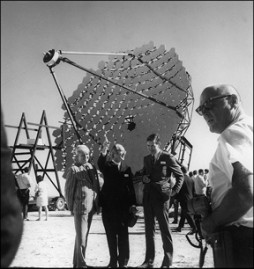

One of many scientific instruments at the South Pole, this telescope records observations that offer clues to the origins of the universe. (Photo by Wayne Clough)

My decision to go to Arizona was motivated not only by my desire to see our operations on Mt. Hopkins but also because we have other important connections in this western state. Among them are a number of Smithsonian friends and advisory board members as well as our partnerships with Arizona State University in Phoenix and the University of Arizona in Tucson. My visit is designed to touch all of these bases.

I am joined on this trip by Under Secretary for Science Eva Pell, SAO Director Charles Alcock, External Affairs Officer Amanda Preston, and Judith Leonard, our general counsel. Just as I am, Eva is using this trip as part of her ongoing effort to personally get to know each of the Smithsonian science centers and to meet the scientists and the staff. Judith formerly served as chief counsel for the University of Arizona and worked with the Arizona State University system; she is helping coordinate our relationships for multiple ongoing projects.

Background

History had a role in the naming of Mt. Hopkins (el. 8,585) and the nearby Mt. Wrightson (el. 9,300 ft.), the two highest peaks in the Santa Rita Mountains. During the Civil War, the Arizona Territory was at odds with itself, having declared for the Confederacy, but being principally occupied by thinly spread Union troops. Confederate troops also claimed a presence in the Territory and both Confederate and Union troops found themselves in a series of running battles not only with each other, but with the Apache people who were fighting to keep their homeland, led by such great chiefs as Cochise, Geronimo, Mangas Colorados and Victorio.

On February 17, 1865, two surveyors for the Union Army, Gilbert Hopkins and William Wrightson, were out on a surveying party and were returning to Ft. Buchanan, their home base. Ft. Buchanan was little more than a collection of buildings manned by a small contingent of the California Militia under the command of Corp. Michael Buckley of the 1st Calvary. Hopkins and Wrightson were surprised and killed by a group of Apache warriors who went on to overrun the fort. The surveyors were memorialized in the names of the two mountains.

The Santa Rita Mountains today are known not only as home to the Whipple Observatory, but also for their natural beauty, nature trails and abundant bird life that draws birders from all over the world.

The observatory on Mt. Hopkins was the brainchild of Fred Whipple, a former director of SAO. In the early 1960s SAO and the Center for Astrophysics partnership with Harvard operated a number of tracking stations around the world, including one in White Sands, N.M. About this time Whipple and his colleagues decided that SAO and CfA “needed their own observatory” at an elevation to minimize the impact of the atmosphere and ambient light from urban areas. Whipple felt the Mt. Hopkins site, with a summit at 8,500 feet, was ideal for this new venture, and that it should be developed in partnership with the University of Arizona. The University of Arizona had a strong astrophysics program along with a one-of-a-kind capability to build the mirrors for large telescopes—today known as the Steward Observatory Mirror Lab.

Important Partnerships

The new strategic plan for the Smithsonian singles out partnerships as a key component of the Institution’s next era. In order to tackle the big ideas that are important to our nation and the world, partners are needed that can provide strengths that the Smithsonian does not have. The ideal partnership is one where each party fills a role the other cannot and together they form a whole that is needed.

The University of Arizona and the Smithsonian have worked together since the 1960s at the Whipple Observatory, sharing costs and providing different elements of the expertise required. Astrophysics as a field is well adapted to partnerships and collaborations, because the high cost of field initiatives is prohibitive for any single institution. These partnerships extend beyond universities and entities such as the Smithsonian to include government agencies such as the National Science Foundation, NASA and a number of major foundations. Today the UA partnership is taking on a new dimension with the planning and execution for what is to become the world’s largest land-based telescope, the Giant Magellan Telescope, slated to be built in the Andes at the Las Campanas Observatory site in Chile. I visited Las Campanas in May 2009 and reported on that trip in an earlier travel journal.

Our partnership with ASU is of more recent vintage and derives from joint research activities in biodiversity by faculty and students of the School of Life Sciences at ASU and our researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Center in Panama. This relationship works well for both parties: STRI provides access to its remarkable resources and ASU brings expertise in forest economics and other fields that complement our capabilities. ASU is also working on an initiative to develop a high-quality digital system that allows virtual participation in field operations. Students and other researchers can benefit greatly by real-time linkage to those working in the field. Early trials have provided exciting results.

March 8, 2011—Phoenix, Arizona

This day is used to meet with the President Michael Crow of ASU in Phoenix and President Robert Shelton of the UA in Tuscon. Like most states, Arizona is dealing with challenging budget deficits, which have in turn impacted the state universities. At the same time, Arizona’s population is growing so there is increased enrollment pressure on higher educational institutions. Enrollment at ASU, the largest public research university in the United States, is 70,440 across four campuses in 2010. At UA, total enrollment stands at 38,057. Both schools are finding innovative ways to address the challenges they face while at the same time continuing strong and vital research programs.

Our meetings reinforce our commitment to our existing partnerships and explore other places where our joint activities might be expanded. While meeting with President Shelton we are pleasantly reminded of one of the main reasons universities are so important to our future—students. During our conversation a student group assembles nearby and their excitment and youthful energy spills over our way. As our researchers know well, our university partnerships create access to students who are willing learners and who bring an enthusiasm to all they do.

ASU scientists Dave Pearson, Juergen Gadau and Smithsonian researcher Kate Ihle walk through field site in Panama. Vidyo technology will bring real time video from Smithsonian tropical research sites into classrooms and connect Smithsonian researchers with ASU students and faculty.

For our part, we are pleased to have these relationships with ASU and UA since they allow us to leverage our impact and reinforce our national leadership role. The Smithsonian is working to strengthen our network of university partnerships. Our upcoming national campaign will offer a unique opportunity to create resources that will support fellowships, interns, joint research programs and visiting scholars.

(Click here for part two of the Arizona journal.)

Posted: 28 March 2011

-

Categories:

Astrophysical Observatory , Feature Stories , From the Secretary , Science and Nature