The William Steinway Diary Project turns a page

Having recently celebrated two major milestones—launching the William Steinway Diary website and opening its related exhibition—the American History Museum’s Diary Project moves toward its next goal. While the exhibition A Gateway to the 19th Century: The William Steinway Diary, 1861-1896 at the American History Museum closed earlier this month, volunteers continue to develop their research, and interlinked annotations will be added to the website over the next few years.

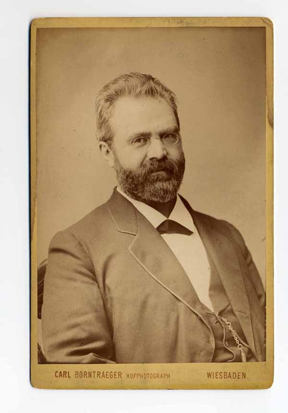

William Steinway, 1882. Photograph by Carl Borntraeger, Wiesbaden, Germany. Courtesy of Henry Z. Steinway Archive

Steinway, a prominent German American and entrepreneur who became a partner at his family’s famous piano manufacturing company at 21, kept an extensive diary covering 36 years of his life and totaling 2,500 pages. As one of the Smithsonian’s longest-running and most extensive volunteer projects, the Diary Project represents the best of the Smithsonian spirit, thanks to the project team’s long-term dedication and remarkable collaborative efforts.

The end of this month marks the 50th anniversary of Cynthia Adams Hoover‘s career at the Smithsonian. She started as a summer intern, eventually became the curator of musical instruments at NMAH, and currently is emeritus curator. She cultivated a long-term working relationship with the late Henry Ziegler Steinway, Steinway’s grandson and former president of Steinway & Sons. Steinway donated his grandfather’s Diary to the museum in 1996.

In the 1980s, Cynthia began collaborating with Edwin M. (“Ted”) Good, a Professor of Religious Studies at Stanford University, pianist, and piano scholar who completely transcribed the Diary over 20 years—a tremendous undertaking. In 2007, Anna Karvellas, managing editor and exhibition curator, and Dena Adams, project coordinator, were brought in to conceptualize and develop a website that would bring to fruition more than 20 years of volunteer work. It was under their direction that the Diary Project achieved recent milestones. Unfortunately, Anna and Dena are leaving the project because funding from a generous gift from the Target Corporation has run out. Stacy Kluck, chair and curator at the Division of Culture and the Arts, and Deborah Richardson, chair and curator at the Museum’s Archives Center, will work with the volunteers going forward.

Diary Project Coordinator Dena Adams and Managing Editor Anna Karvellas at a reception celebrating the launch of the William Steinway Diary Web site and opening of the related exhibition. (Photo by Harold Dorwin)

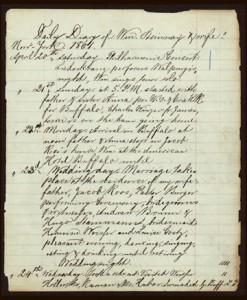

William Steinway was a very detail-oriented person, as noted by his records of nautical miles and train times, and the Diary has incredible depth, covering numerous topics: William’s first-hand, honest account of the horrors of the Civil War draft riots; piano manufacturing and labor issues; banking and financial crises; the impact of the telegraph and telephone; and the development of the New York City subway system. So, the volunteers have had plenty of material to research, with more than 12,000 assignments distributed to date.

“Daily Diary of Wm. Steinway & wife!” The William Steinway Diary, 1861–1896. Courtesy of the Archives Center, National Museum of American History. The first page of William Steinway’s 36-year diary, beginning three days before his wedding. Although the diary belonged to William, his choice of title conveys his joyful anticipation of his wedding.

Each of the dynamic and diverse volunteers, some of whom travel from as far as Michigan and Maine to attend researcher meetings, brings his or her unique skill sets to the project. With backgrounds in academia, economics, journalism, law, nonprofits, the military and many federal government branches, many of the volunteers say that the most rewarding aspect of the work is bring their own particular expertise to the project. Others said they appreciated the personal insight into the 19th century and distinguishing what in the Diary is uniquely “William.” A selection of some of the most active volunteers associated with the project can be found here.

Milton (Milt) Lum, currently assigned at the pediatric department at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, has created a spreadsheet to systematically track and cross-reference William’s multiple infirmities throughout the Diary. This data set provides a meaningful understanding of William’s ailments and has direct applications for the Steinway family. Kathryn (Kathy) Morisse, a retired economist, focuses on transportation and trans-Atlantic shipping. She works closely with another retired economist, Karen Johnson, on tracking William’s development of the western part of the borough of Queens in New York through the Astoria Homestead Company.

A Steinway & Sons Grand Piano made in 1892. It was played by Ignace Jan Paderewski on his first United States tour (1892-1893). Paderewski signed the frame, “This piano has been played by me in 75 concerts during 1892 and 1893.” Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

At a recent monthly researcher meeting, John Bowen quoted from an article he read in the New Yorker, “Joining a group that meets just once a month produces the same increase in happiness as doubling your income.” Laughing, the other volunteers agreed. A number of volunteers have devoted a significant amount of time to the Diary Project, especially John R. (Dick) Anderson, an expert in piano labor who has volunteered on the project since 1989. Together, more than 100 volunteers have logged over 28,000 hours of research.

Most of the volunteers came aboard the project after meeting with an interviewer from the Visitors Information and Associates Reception Center, who paired their qualifications and interests with the Diary Project. “This office has just been invaluable to us for all these years,” Cynthia said. Several other units assisted in bringing the project to life, as well. Ching-Hsien Wang, supervisory IT specialist in the Office of the Chief Information Officer, went above and beyond her job responsibilities, and helped the project team find a partner to launch the website. Anna said of David Allison, associate director for curatorial affairs at NMAH, “His belief in the project really opened doors for me.” She also praised photographer Hugh Talman, whose work in New York photographing Steinway materials led to the nickname “Commando Archivist,” an honorific he shared with Dena. Several other SI units worked with the project team, including NMAH’s Archives Center, Division of Culture and the Arts, Albert H. Small Documents Gallery team, Smithsonian Institution Libraries, NMAH’s New Media Program, and others at OCIO, including the Digital Asset Management System group.

Researchers pore over material at a meeting for The William Steinway Diary Project. (Photo by Hugh Talman)

The Diary Project exemplifies our Strategic Plan to broaden access to the public, and it also serves as a model for future archival documents that would benefit from being digitized, such as Thomas Jefferson’s bible. It is an excellent example of how the public can benefit from having easy, digital access to Smithsonian collections and objects. Anna said, “We have heard wonderful things about our digital accessibility, and we are proud to share this remarkable diary with the world. Research collaborations from afar are something we will begin to see more and more.” Students writing dissertations already have found the Diary invaluable, and sections of the Diary will be included in The Modern Library’s Anthology of New York Diaries, which will be published in August 2011. In just four months, the website has received over 10,000 visits, garnered significant press, and was nominated for two Web awards, including the American Association of Museum’s MUSE Awards.

“Why did William keep the diary in the first place?” volunteer John McClenahen asked. This question remains unsolved, but one thing is certain: Each volunteer and contributor has been so vital to making the Diary Project a success that if any one were removed, the project might not have made it this far. And more work is needed to accomplish the next phase of research and annotations. If you would like to see how you can contribute, visit The William Steinway Diary Project.

William Steinway Diary Project volunteer researchers and staff, 2010. Top row: Ken Bailey, Larry Herman, Susan Welch, Anna Karvellas, John McClenahen, Charley Donnelly, John Bowen, Dena Adams, Ken Maniha, Jan Benson; bottom row: Carol Sue Fromboluti, Valerie Estes, Milton Lum, Edwin M. Good, Cynthia Adams Hoover, Dick Anderson, Karen Johnson, Kathy Morisse, Greg Morris, Heidi Varblow, Linda Smith (Photo by Hugh Talman)

Posted: 29 April 2011

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture

Thanks for the reference to Smithsonian Libraries. We were happy to provide assistance to the project for over five years.