On the Road in Panama: Part two of the Secretary’s travel journal

Arrival in Panama City—January 31. Temperature around 85 degrees, warm, sunny and pleasant

This is summer in Panama and a good time of year because it is the dry season with low humidity. Our flight is routed over the ocean in its approach to the airport, which affords a panoramic view of the flotilla of ships waiting to be locked into the Canal for their trip to the Atlantic Ocean. As we bank, we see the sweep of the high-rise buildings of Panama City that line the shore. Panama City today is vibrant and growing and, in contrast to much of the rest of the world, the economy of Panama is thriving. The drive from the airport confirms what we have seen from the air, construction abounds—not only buildings but also a new underground metro system.

We are greeted at a reception hosted by Panama’s Vice President, Juan Carlos Varela, to celebrate the 100-year-old relationship between the Smithsonian and the country of Panama. The reception is held at Panama La Vieja (Old Panama), the site of the original Panama City that was later abandoned after it was sacked by the pirate Henry Morgan. The beautiful setting and the perfect weather are an auspicious introduction for the Smithsonian National Board’s tour of our facilities in Panama. It is also a nice touch that Vice President Varela and two of his brothers are alumni of Georgia Tech, as I am.

February 1—Morning temperature low 80s and breezy

We arise to another nice day and proceed to STRI’s headquarters, the Earl S. Tupper Center in downtown Panama City. The Tupper Center houses STRI’s principal science laboratories and administrative offices. Although the Center is an excellent modern facility, it is land-locked and cannot accommodate STRI’s growing research activities. Later in our trip we will visit STRI’s complex at Gamboa and break ground on an expansion of new scientific facilities there.

Agua Salud

The morning is given over in part to briefings by Eva Pell, our Under Secretary for Science, and Biff Bermingham, STRI’s director. Eva shows how the STRI’s work fits into the larger Smithsonian science agenda, while Biff illustrated STRI’s history, strategic plan and future direction. One of the projects Biff describes is the canopy crane and our work at Agua Salud. Although we will not get to Agua Salud on this trip, I had the opportunity to see it on my first visit to STRI in 2009.

The participation of local farmers is integral to the Agua Salud reforestation project. Photo by Patricia Bartlett

The Agua Salud project is a critical initiative sponsored by the Panama Canal Authority designed to create an understanding of the interplay of forests and the freshwater supply that is critical for the operation of the Canal locks. It involves a large-scale field study investigating water retention and flow both through areas of natural forest and those where attempts are being made to re-establish the forest after extensive logging or other cuts. The native people who farm along the Canal are an important part of the project as they are involved in choosing species for reforestation that benefit both the farmers themselves and the entire ecosystem. Agua Salud is a long-term effort because it takes time for the forest to re-establish itself.

Canopy cranes allow scientists to observe the forest ecosystem at every level. Photo by Patricia Bartlett

Canopy cranes have been in use for some time in forests to allow researchers to access various levels of the forest canopy and conduct long-term observations. This is critical in a tropical rain forest where species of trees, animals and insects occupy different niches at different levels where they compete for resources such as access to sunlight. The first canopy crane in the world was built at Agua Salud under STRI’s auspices in 1990 and we were able to visit it on my first trip. When we arrived we were greeted by a group of researchers from Stanford University who were using the crane to correlate with findings they were making using remote sensing techniques. In groups of two to three we were given the opportunity to ride in the canopy crane observation cage—walls and floor of steel screen and a large window for observation. The screen floor allows the rider to see below, and as the cage rises and the distance from the ground increases, it gets your attention. The observation cage can be extended out along the boom to the very end and if the wind is blowing, as it was when we were there, the cage sways, ever so gently, high above the ground.

The ride up and out along the boom provided an amazing view of the canopy. Each stage made us appreciate how this remarkable ecosystem changes both vertically and laterally. Ants and other insects were busy traveling along the limbs working at their jobs of providing food for their clan while also serving to protect the trees by warding off other insects and small animals that enter their territory. As we rose, we came close to a three-toed sloth that was enjoying its rest and did not particularly appreciate our intrusion. As we neared the top of the canopy some 70 or 80 feet up, we could see the Canal in the distance. A troop of howler monkeys made their booming sounds to warn others of their species about our presence.

While the trip up was spectacular there was a small sense of relief as we began to descend. Upon reaching ground, our legs took a few minutes to fully forget the sensation of swinging in the breeze. The canopy crane is a remarkable experience not to be missed.

Biomuseo

After a morning of business meetings at the Tupper Center, we are transported to the soon-to-be opened Biomuseo, a natural history museum designed by world-renowned architect Frank Gehry with his typical flair. The museum‘s outline with its irregular, brightly colored angular roof expresses the flowing canopy of a tropical rain forest and the colors of the birds and wildlife in it. Beneath the nonsymmetrical lines of the roof, the museum itself is designed to tell the natural history and human story of Panama and the Isthmus, from the time before the joining of the continents, to the creation of the land bridge, the arrival of humans and the marvelous biodiversity of the land and the oceans. Much of what will be seen in the Biomuseo derives from STRI’s research. The museum is located on Punta Culebra, a peninsula offering views of Panama City that is also home to STRI’s educational center. The center attracts more than 100,000 visitors a year to its aquarium and educational programs.

In spite of its exotic appearance, the spine of the museum is essentially a straight line that aligns the exhibit halls and galleries with the visitors’ atrium. Looking up, visitors in the atrium see the soaring roof elements zigzagging at different angles. The pieces are not intended to connect as they approach each other, leaving openings that will allow rain to fall as it may, just as it does in the rain forest itself.

Reflecting the museum architecture, the exhibits will be dramatic, including one “wonder” item in each gallery or hall. Full-scale wall videos will show exciting views of flora and fauna. The galleries and halls will tell the story of what it was like before the Isthmus was present and the transformation that occurred when it was formed. I hope to return to see all of this in its final form. It will be an exciting experience for Panamanians and visitors alike.

February 2—Weather warm and comfortable, low 80s

Reveille is early this morning, and we are off to visit Barro Colorado Island, famous in Smithsonian and natural science history. Our transportation will be unique because we will arrive via the historic Panama Canal Railroad, first built by U.S. interests in 1852, well before the Panama Canal. At 47 miles long it is one of the shortest rail lines in the world, but in terms of freight hauled and importance it stands as one of the most significant. It serves as an alternative to the Canal for container freight to transit the Isthmus and last year the line delivered 420,000 containers. It also services the needs of Panamanian commuters and cruise-line tourists with passenger trains several times a day between the coasts.

Barro Colorado Island

The tropical forest of Barro Colorado Island are among the most studied in the world. Photo by John Gibbons

Upon disembarking the train, we take a “class picture” and board boats to Barro Colorado Island in the middle of Gatun Lake. Over breakfast, Stuart Davies of STRI describes the important work of Smithsonian Institution Global Earth Observatories. The history of SIGEO is grounded in the research performed on BCI, where the techniques for long-term observations of forests were established. Under the leadership of former STRI director Ira Rubinoff, the idea was developed to extend and standardize the monitoring techniques developed at BCI to tropical forests around the world by working with collaborators who would share data through a combined database. Stuart brings us up to date on the network, noting it has grown to 46 sites in 21 countries and now includes temperate and savannah forests as well as tropical forests. The database serves the science community with a rich resource for understanding the long-term impacts of deforestation and climate change.

After the lecture we break into groups of 10 for a walk through the wonders of BCI accompanied by expert guides—but not before stuffing our pants cuffs into our socks and taping them up to prevent insect hitchhikers from latching onto our ankles and legs. The most prevalent of these are ticks and chiggers, the latter of which would love to go along for the ride home to the U.S. Our guide is the inimitable Bert Leigh, who first came to BCI in 1969, fell in love with it, and never left. He is the author of A Magic Web, along with photographer Christian Ziegler—a book that explains the ecosystem of BCI though the lens of science and as captured in remarkable photographs. It has been reissued recently with an update on the science and new photographs and it is stunning.

Our hike takes us up into the rain forests at a nice pace that lets you know you are climbing, but allows Bert to stop often to give us his observations accumulated over a lifetime. The diversity of BCI is amazing; even more interesting are the symbiotic relationships that exist between the insects, animals and flora. Everything has its place and its time. Trees drop nuts in locations where animals like the agouti, a rodent the size of a house cat that inhabits tropical forests, pick them up and bury them in places where they can sprout and spread the species. Fig trees that soar 50 to 80 feet in the air are pollinated by tiny wasps. Ants nest in bushes and trees where they find food and in return, protect the plants and trees that host them by aggressively attacking invaders to their territory. The understanding of these relationships and so much more has come from seven decades of ongoing research and observation that continues to provide insights into the complex natural world of the tropical rain forest.

On our hike, we see many animals and insects, including stingless bees and a three-toed sloth that is a bit aggravated by our presence and moves, slowly, up a tree to get farther away from us. An agouti is surprised as we arrive and trots past us as we try to get pictures. Apricot Sulphur and Tiger Longwing butterflies flutter by and we are startled by the presence of a bird-eating snake sunning itself on our path. Even though they are asleep at this time of day, I know that bats are nearby. On my first visit to BCI, we stayed overnight and several bats came by our room to check us out.

Taking a short hike to learn about biodiversity on BCI is like making a 30-minute visit to the Louvre to check out the great masters. It is simply not enough, but it does allow a deeper appreciation of the wonders described in Bert’s book. We also have the privilege of listening to the master himself as he draws on his deep knowledge of BCI and its wonders and secrets. If we are to help the great tropical rainforests survive, we can only do so with the knowledge of dedicated scientists like Bert and Stuart and other STRI scientists like them.

We cannot stay at Barro Colorado as long as we would like because we are traveling on to nearby Gamboa for the groundbreaking of a new facility there. We board a boat for a ride across Gatun Lake. The trip allows us to see up close the behemoth cargo ships that carry massive numbers of containers or bulk freight through the canal, reminding us that this is truly the intersection of world trade.

Gamboa

Gamboa was born as a company town for the U.S. Panama Canal Authority and supported the work of the construction of the Canal. Today it is used by the Canal Authority as a staging area for the dredging work that is done almost continually to keep the Canal ship channel at the proper depth. The Smithsonian has long used Gamboa as a supply and staging site for BCI, but recently, STRI has begun to expand the science facilities at Gamboa to allow for growth that can occur here but not in Panama City. We will learn about some of the science that is done here and will participate in groundbreaking for a new $17 million science facility.

Before we arrive at the STRI science labs, Biff takes us on a tour of Gamboa, which is small enough for us to see it in 30 minutes. Most of the buildings in the town were built by the U.S. Panama Canal Authority in the early years of the last century and are historic. STRI has purchased many of the houses for the use of its own staff and visiting scientists. A long-term effort is underway to restore the historic facilities in the town and on the science campus to their original condition.

Klaus Winter is a senior scientist at Gamboa; his work focuses on the effect of global changes that are impacting tropical rain forests, particularly growing levels of carbon in the earth’s atmosphere. He and his team are able to simulate the elevated carbon levels by using large glass-encased chambers housing tree species that respond differently to carbon effects. His results have attracted the attention of the science community around the world.

The main item on our agenda is the groundbreaking, and we are joined by several participants from the Panamanian government who have an interest in the research facility and the science that will be done there. Steve Hoch, the chair of the newly formed STRI board, opens the celebration with his remarks and Biff and I follow. The afternoon is pleasant and fragrant from the flowers of the rainforest. The groundbreaking is officially completed by shoveling dirt at the site of the building.

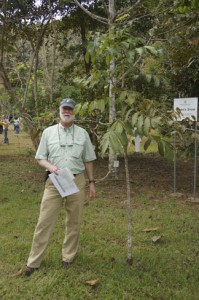

After the formalities a few of us check out the condition of the trees we planted in 2009. My tree is still there, but I have to say, others planted at the same time seem healthier. For example, my wife’s tree is now 20 feet high, while mine is only about 6 feet tall and they are the same species. I bring this to Biff’s attention, but am informed that it is up to nature to determine the growth rate. So I leave hoping that nature will give my tree a little more attention in the future.

As we close this day’s work, we board a bus for the hour ride to our hotel in Panama City. In the evening we attend a dinner that features the Fundacion Smithsonian de Panama, a group of Panamanian businessmen who provide support for STRI. It is a good opportunity to meet them and to renew our joint commitment to the future of STRI.

February 3—Warm and breezy with clouds and a hint of rain in the air

Today we will go to the excavation of the Canal expansion on the Atlantic side of the Isthmus in Gatun. On our bus trip we hear from Esteban Saenz of the Panama Canal Authority. Esteban is one of those people who is able to tell a complex story in down-to-earth terms and he inspires confidence with his knowledge and understanding of how the Canal operates. He tells us about the existing locks and the new “Third Locks” under construction. Excavation began in 2009 and if progress remains on target, the Third Locks will open in 2014. At $6 billion it is one of the largest construction projects underway in the world.

The existing locks, 110 feet wide and 1,050 feet long, have been in continuous operation since 1914 and are one of the engineering wonders of the world. Over time, the demand for transit through the Canal has expanded and the size of ships has grown. “Panamax” is the term used to describe the maximum ship size that can pass through the canal at present. Larger ships offload at West Coast ports like Los Angeles where cargo is loaded onto trains that carry it to points east. The Third Locks will handle what will be known as “New Panamax” ships with lock chambers 180 feet wide and 1,400 feet long. New Panamax ships carry 12,000 shipping containers (think of a semi truck) as opposed to the Panamax capacity of 5,000 containers. The new construction includes two sets of three chamber locks, one on the Pacific side near the present Mirafores Locks and one on the Atlantic side near the present Gatun Locks.

This "Panamax" ship has a capacity of 5,000 shipping containers. The new Third Locks will allow ships with a capacity of 12,000 containers to pass through the Panama Canal. (Photo by John Gibbons)

The impact of the Third Locks will be enormous, increasing the revenues flowing to the Panama Canal Authority and the country of Panama, but also changing the equation for all of the ports on the east coast of the United States. Already, ports such as Houston, Baltimore, Charleston and Savannah are dredging their harbors to handle the New Panamax ships that will begin arriving in 2014. On the other side of the country, Los Angeles and San Diego are improving efficiencies to offset any losses of traffic to the Canal.

STRI’s work intersects directly with the Canal, especially regarding our science understanding the fresh water supply deriving from the forests and rivers adjacent to the Canal. The original locks are operated using fresh water which is “lost” each time the lock is opened. To minimize the need for fresh water, the Third Locks will recycle up to 60 percent of the water used to operate the locks.

STRI scientist Carlos Jaramillo (right) takes me on a tour of the rich fossil record at a cut near the Gatun Locks. (Photo by John Gibbons)

The principal fresh water source for the Canal is the Chagres River, which was damned during the construction of the original locks to create Gatun Lake. Recently, flow from the Chagres has fluctuated more than in the past, and there are concerns that climate change will make these fluctuations more dramatic in the future. In 2010, the flow from the watersheds into the Chagres exceeded 300-year-flood levels at the same time water had been released into the lake from the dam in preparation for the dry season. This led to considerable stress on the systems of the Canal and flooding resulted downstream. Because of the concern about the fresh water supply, both in terms of “too much” and “too little,” STRI has been engaged in study of the issues through projects like Aqua Salud.

As our bus approaches the Gatun Locks we stop at a location nearby where a large cut has been made in what is termed the Gatun Formation. The cut was made to obtain soil and rock to be used for fill at a nearby housing and retail development. Geologically, the materials in this area are relatively recent and moderately consolidated sedimentary rocks. The STRI science team led by Carlos Jaramillo is interested in this location because 10 million years ago it was a shallow marine basin, rich in marine life, particularly sharks, which used it as a nursery. As we walk toward a bluff from which soil and rock has been removed, we can look down and see thousands of fossils of small marine creatures. Carlos and his team members tell us about the history of the site and then stroll with us as we examine the plentiful supply of fossils and shells, all from millions of years ago. Among them are the tight spirals of the Turritella, or turret shell, beautiful Conicas or cone shells, the graceful Ovlia or olive shell and skeletal remnants of Euphylax or the swimming crab.

Less frequently, our group finds shark teeth. Our guides assure us there are many to be found, but you need a practiced eye. A number of shark species lived in the shallow marine seas that existed 10 million years ago, the largest of which was Megalodon, with lengths reaching more than 50 feet. Most of the Megalodon teeth in this deposit are from smaller specimens, leading to the belief that these were young sharks, being protected in the nursery. All of these fossils and those at other sites have allowed STRI scientists to develop a new understanding of how the Isthmus of Panama developed and how its unique species evolved over time. This is an exciting time to be a scientist at STRI.

We depart this site reluctantly feeling that with time each of us might find a Megalodon tooth, but we must push on as we are due to at the Gatun Lock to watch as a Panamax-sized ship passes through. We are greeted at the Lock by an enthusiastic tour guide working who explains the steps involved in getting the ship from Lake Gatun into the lock chamber and waiting as the water releases to lower the ship to sea level. Four powerful mechanical “mules” that are linked to the ship with cables perform a delicate ballet as they loosen and tighten the cables to insure the ship does not strike the lock walls as it moves from the chamber towards its eastward goal, the Atlantic Ocean. This is no simple task, as the huge ship fits snugly into the lock chamber with only a few feet to spare on each side. This job is done over and over again each day with precision, although it can be seen from the lock walls that some hits have occurred now and then—but not bad, given that, as mentioned, the locks have been in continuous service since 1914.

There is little margin for error as a ship makes its way through the Gatun Lock. (Photo by John Gibbons)

Our last stop is to the visitors’ overlook for the new lock structure. This overlook is not yet open to the general public, so we are lucky to be among the first to take in what is a remarkable view of the construction. The site is something out of a Cecil B. DeMille movie set with hundreds of workers and dozens of trucks scurrying about with loads of rock and earth amid massive excavations for the locks. The scale is hard to reconcile with its staggering proportions.

As we watch the work we are treated to a lecture on the care taken with the ecology of the site and the efforts that will be made to restore it after construction is complete. STRI student interns and researchers have set up tables exhibiting some of the fossils that have been found in the lock excavations. As if on cue, a large harlequin beetle flies in and lands on a concrete step. A colorful fellow, he is a creature of the tropical rain forests who seems to be checking out the new facility.

Finally we load onto our buses for the ride back to Panama City. We zip back along a toll road and arrive at the hotel after about an hour and 45 minutes ride. An amazing country—we have crossed it from coast to coast and back again in one day, with allowances for three stopovers.

In the evening we close our activities with a casual dinner at STRI’s Punta Culebra education facility. As night falls, enjoying the beautiful views of Panama City across the water with good friends on a warm Panama evening is a wonderful way to end the day.

Many of the Smithsonian National Board members will travel on to Bocas del Toro, STRI’s Marine Center on the Caribbean. I have to return to Washington, but I am glad to have had the chance to renew my acquaintance with colleagues, meet those who are new to STRI and gain a deeper understanding of the important work being done at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Read Part One of the Secretary’s travel journal describing the hundred-year history of the Smithsonian’s relationship with the country of Panama. Take a video tour of Barro Colorado Island.

Posted: 29 February 2012

-

Categories:

Feature Stories , From the Secretary , Science and Nature , Tropical Research Institute