On the road in Hawaii III: The Secretary’s travel journal

In Part III of the Secretary’s journal, explore the ecology of the coral reef with one of the world’s foremost experts. Don’t miss Part I and Part II.

Saturday, September 1, 75 degrees and partly sunny

Today we will transition from 13,000 feet to sea level for a visit to Mary Hagedorn, a reproductive biologist at the Smithsonian’s Conservation Biology Institute and her colleague in the study of coral from the National Zoo, Mike Henley. They will take us snorkeling in Kanehoe Bay to get a firsthand look at a coral reef they are studying. We drive northeast across the island on the Pali Highway and meet Mary and Mike at the Pali Lookout, where the highway crosses the crest of the Koolau mountain range. The Koolau Mountains were formed from a massive volcanic caldera that is being constantly reshaped by landslides and erosion, forming steep cliffs and deeply incised gullies. From the Pali Lookout the view of the mountains standing high above Kaneohe Bay is striking. Distant rain showers glide across the lowlands and the Bay while winds push up the slopes of the mountains whipping the tops of the trees back and forth.

Historically, Pali Lookout is the location where a crucial battle was waged in 1795 by Kamehameha the Great to consolidate his control over all of the islands of Hawaii. As the opposing forces retreated up the mountain many were trapped at Pali Lookout and hundreds chose to leap over the cliff rather than surrender.

Mary uses this vantage point to point out the coral reefs in the Bay that can be seen as light, almost circular areas in the aquamarine water. She explains that the reefs are critical to the ecosystems of coastal waters, providing a home for thousands of fish species and other marine creatures; coral reefs also absorb carbon from our atmosphere just as tropical rain forests do. Unfortunately, coral reefs are under attack from polluted mainland runoff, disease, silting, warming oceans, and indiscriminate fishing using explosives and other illegal approaches. In the Caribbean and other areas around the world, coral reefs have deteriorated significantly; those that remain are under stress.

Mary Hagedorn describes the coral reefs in Kaneohe Bay from the vantage point of Pali Lookout. Mike Henley is in the foreground. (Photo by John Gibbons)

Mary explains why Hawaii is such an ideal place to conduct coral research. Hawaii is home to 70 percent of the coral reefs in the United States, and although there are danger signs from some disease and damage, there are still large areas of healthy corals, offering the opportunity to understand the life cycle of this remarkable invertebrate. Mary is a world-renowned specialist in coral reproduction and in using her knowledge to replenish and reestablish reefs.

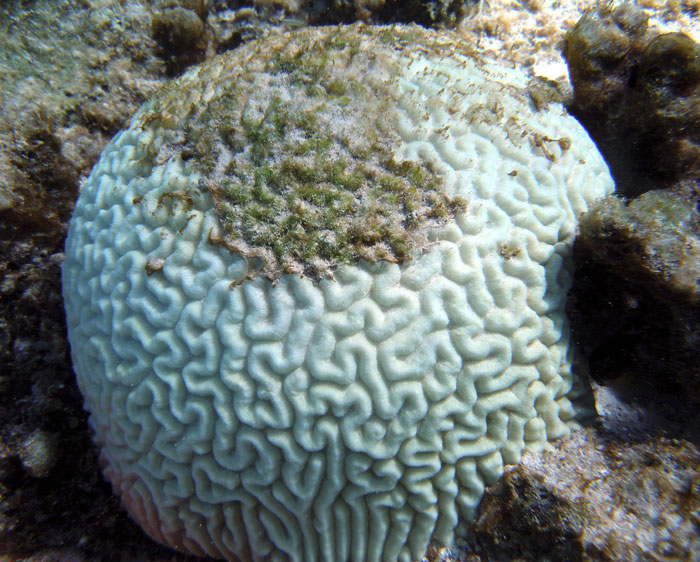

Corals are a relatively primitive form of life, consisting of approximately ten different types of cells. In spite of their seeming simplicity their systems and ecology are complex and are still being deciphered. Following the ancient rhythms of the lunar cycle, coral reproduce by ejecting eggs and sperm to mix and fertilize. This process is called spawning and we will have an opportunity to observe it Sunday night at Mary’s laboratory on Coconut Island. Corals form colonies that become reefs. Spawning creates tiny coral larvae that seek to attach themselves to the reef. Corals and algae are symbiotic species, with the algae, known as zooxanthellae, providing food to the coral through the process of photosynthesis. Zooxanthellae provide color to coral; if the algae die, the coral turns white or is “bleached.” Zooxanthellae also apparently provide signals to coral larvae as they seek to establish a colony site. Coral reefs form ideal homes for fish, turtles and invertebrates, giving them protection from predators and providing a platform for food. In return, fish help clean the coral and keep it healthy.

Mary is a pioneer in more ways than one. First, her work has led to breakthroughs in understanding how coral reproduce and in developing techniques to cryogenically store coral sperm and larval cells so it can be used to restore coral reefs. This is no simple matter and required years of experimentation. Second, she has done most of this work on her own relying on one or two staffers and students who have worked with her in internships and thesis studies. The Smithsonian has encouraged her work and provided basic support, but her relationships with the Marine Sciences program at the University of Hawaii has also been a key in providing facilities and students. Only recently, has she received the attention she deserves, including an article in the New York Times Science section.

Today, Mary and her husband, Ned, are hosting us at their home. The house has a wonderful lived-in quality, having once served as a local post office. It lies on a strategic point in the Bay with beautiful westerly views of the Koolau Mountains. We are blessed by beautiful weather, sunny with a slight overcast that keeps the heat down. Each of us is outfitted with a snorkel mask and swim fins for our adventure. Our transportation is provided by Mary and Ned’s trusty covered pontoon boat. Not built for speed, the craft is just the ticket to allow for a slow ride to the reef, perfect for observing the waters along the way.

As we depart we notice a beautiful umbrella shaped tree at the shoreline below the house—a monkeypod tree. The tree is not native to Hawaii; in fact, Mark Twain himself planted a monkeypod tree on a visit to Oahu that is still thriving. Known formally as albizia saman, the monkeypod is also known as the “rain tree” or “5 o’clock tree” because of its habit of closing its leaves when it rains and at night. Its beauty comes from the spreading symmetrical shape of the branches. The tree’s height ranges from 50 to 80 feet and the diameter can grow to more than 100 feet. It has a delicate pink flower that contrasts wonderfully with the green of the leaves. It reminds me of the mimosa trees that were common in south Georgia where I grew up.

Our destination is known simply as “Reef 42,” a prosaic name for what is in reality an underwater wonder. As we approach the reef large three- to four-foot green turtles rise from the deep waters to investigate us and our intentions. Seemingly finding us harmless, they go about their business and disappear. Ned insures a good anchorage and we jump into the warm water and swim towards the reef. I have never used a snorkel before and the process requires some practice to avoid getting salt water up my nose. I get the hang of it and soon am able to glide through the water, which is about three or four feet deep above the reef surface.

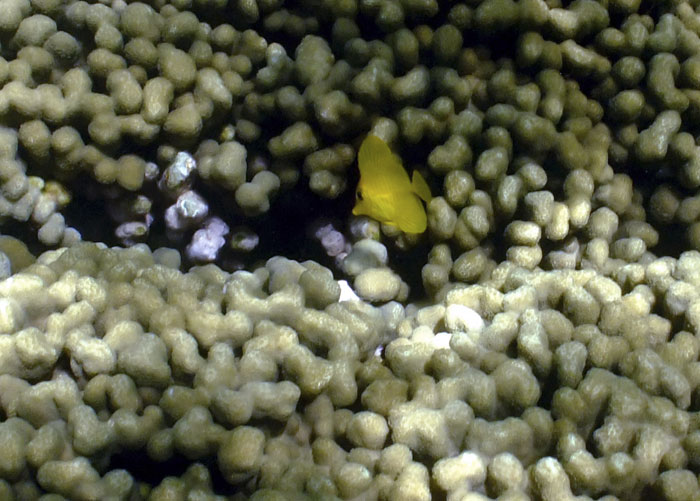

Mary and Mike have prepared us for what we will see—a variety of corals, different species of tropical fish and green turtles. We have been warned that we will not see large numbers of fish, or large specimens, because this area has been overfished by both professionals and amateurs seeking tropical fish for aquaria. Even so, the sight that greets us is straight out of a nature documentary. The reef is a montage of rice coral (Montipora capitata), mushroom coral (Fungia scutaria) and finger coral (Porites compressa), each exhibiting different shapes and colorations and forming ever changing patterns. It brings home the fact that a reef exists as one large organism formed from hundreds of thousands of individuals that work together in a complex system to survive.

As noted, the reef fish are not large, but those we see are delightful and colorful. A Yellow Tang with its dramatic sail-like shape and striking color swims in and out of the cavities in the reef. A school of pencil-thin and purposeful Needlefish cruise by, moving in unison and in a straight line. The colorful Saddle Wrasse work the top of the reef looking as distinguished as if they had just stepped out of GQ Magazine. It is sad to think the numbers of these amazing creatures have been diminished, not only for the fish species themselves, but also because they are crucial to the survival of the reef.

The largest resident of the reef, the green turtle, also finds the reef a place of respite, lying low in shallow bowls or recesses in the reef. Although these noble creatures do not spook when we swim nearby, one gets the impression from their baleful looks that they had rather we not be there. If we linger too long they will finally power up, and in spite of their size, swim gracefully and with surprising rapidity away to the deep.

As much as we are enjoying ourselves, time arrives for a return to Mary and Ned’s house. This experience has been not only pleasant but particularly educational for me since I have only heretofore seen reefs from a distance or from a boat. I will have a better understanding of Mary’s work when we visit her labs tomorrow, having seen the fullness of the reef ecology and its intricate structure.

Johnny and I take a route back to our hotel recommended by Mary to allow us to see more of the marine environment of Hawaii. We follow Kalanianaole Highway as it winds around the most eastern point of Oahu, an area famed for its state parks and dramatic rocky seashore pounded by large waves and raked by strong winds. The scenery lives up to its billing and we have to be careful not to spend too much time looking at it while we navigate the winding roadway. These park lands show Hawaii at its best and illustrate why it is so easy to fall in love with this island state.

Posted: 21 September 2012

-

Categories:

Collaboration , Feature Stories , From the Secretary , Science and Nature

Secretary Clough, thank you for your thoughtful and moving comments on the Hawaiian corals and your visit. As a new SCUBA diver, I relish hearing of others’ experiences with our great ocean. In April, I participated in two projects dear to me–Coral Restoration, Key Largo, and international fish count–always good to be reminded of our small place in the world. Susan