“Blackness is what I know best.”

As Black History Month winds down, consider these portraits of six iconoclastic African Americans who remind us that history is written every day, by each of us.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, by Winold Reiss, 1925. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Lawrence S. Fleischman and Howard Garfinkle with a matching grant from the National Endowment for the Arts

Sociologist and historian W.E.B. Du Bois originated the policies—legal suits, legislative lobbying, and public protest—that characterized the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. In the early 1900s, he organized protests against the increasing racial violence that spread from the South into northern cities. Breaking ranks with Booker T. Washington and his policies of accommodation and gradualism, Du Bois called for immediate civil and political rights for African Americans. He founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1910 and became editor of its monthly magazine, The Crisis. Du Bois’s disillusionment after World War I attracted him to Marxism and led him to question the efficacy of legal and political tactics to end racism. He eventually became a citizen of Ghana. Du Bois was the author of such classic works as The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and Black Reconstruction in America (1935).

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

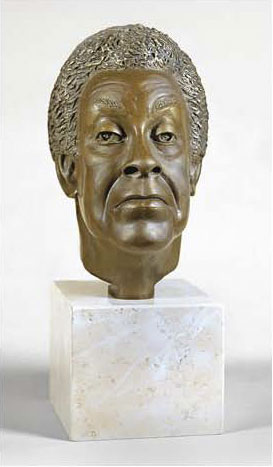

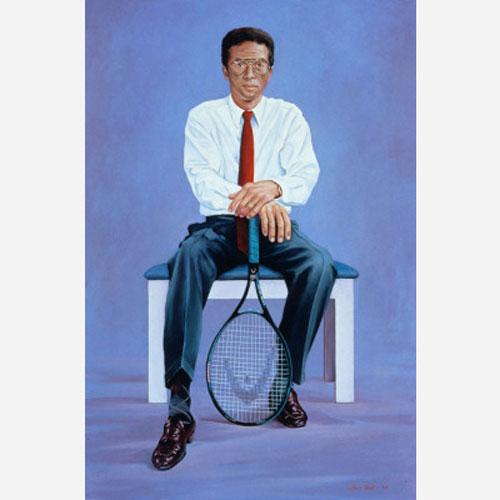

Arthur Robert Ashe, Jr., by Louis Briel, 1993. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of the Commonwealth of Virginia and Virginia Heroes, Inc.

Armed with superb natural talent, a keen competitive spirit, and poise that set him apart from his rivals, Arthur Ashe made his way from the segregated playground courts of his youth to the pinnacle of the tennis world. Rated among the world’s top-ten players while still in college, Ashe reached the number-one ranking in spectacular fashion in 1968. After capturing the U.S. amateur title, he served an astonishing twenty-six aces in the final to become the first African American man to claim the U.S. Open championship. Ashe went on to record multiple tournament victories, including his memorable triumph over Jimmy Connors at Wimbledon in 1975. Following a heart attack that forced his retirement in 1980, Ashe dedicated his energies to humanitarian causes. He became a leader in the fight against AIDS in 1992, after revealing that he had contracted the virus through a transfusion.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

“Blackness is what I know best. I want to talk about it, with definitive illustration,” said writer Gwendolyn Brooks. From her sensitive autobiographical novel Maud Martha to her popular rhythmic poem “We Real Cool,” Brooks devoted her work to portraying urban African American life with poignancy, artistry, and pride. During the course of her career, Brooks received two Guggenheim Fellowships and became the first black writer to receive the Pulitzer Prize and earn election to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. Brooks wrote of this sculpture: “Sara, thank you for extending my life; for sending my life into bronze and beyond.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

"Cat's Cradle" Mohammad Ali by Henry Caselli, 1981. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of the Sig Rogich Family Trust. Copyright 2002, Henry Casselli

When Muhammad Ali proclaimed “I am the greatest,” it was hard not to agree. Just twenty-two years old when he stunned the boxing world by upsetting heavyweight champion Sonny Liston in 1964, Ali (born Cassius Clay) would become the first three-time winner of the heavyweight crown. A consummate showman whose braggadocio and rhyming banter captivated the public, the fleet-footed and graceful Ali was mesmerizing as he confounded opponents with his unorthodox boxing style. Ali was also a potent force beyond the ring. In 1967 he became a symbol of conscience to many when he was convicted of draft evasion and stripped of his title after refusing military induction on the basis of his religious beliefs. The Supreme Court later overturned the conviction, and Ali battled back in the ring to regain the heavyweight title in 1974.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Asa Philip Randolph, by Ernest Hamlin Baker c. 1945. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph waged a lifelong battle for the economic empowerment of African

Americans. In 1925 he accepted the challenge of organizing the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters—the

first black labor union chartered by the American Federation of Labor. Continuing his advocacy for African

American workers, Randolph called for a march on Washington in 1941 to protest the exclusion of blacks

from defense industry jobs. He cancelled that march only after President Franklin Roosevelt signed an order

mandating an end to discriminatory practices by government contractors. Following World War II,

Randolph led the effort to desegregate the nation’s armed forces and waged a civil disobedience campaign against

the draft until President Harry Truman ordered an end to segregation in the military in 1948. Randolph crowned his

career in 1963 by helping to organize the celebrated March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Marian Anderson by Betsy Graves Reyneau 1955. National Portrait Gallery, gift of the Harmon Foundation.

Arturo Toscanini said that Marian Anderson had a voice that came along ―once in a hundred years.‖ When one of Anderson’s teachers first heard her sing, the magnitude of her talent moved him to tears. Because she was black, however, her initial prospects as a concert singer in this country were sharply limited, and her early professional triumphs took place mostly in Europe. The magnitude of her musical gifts ultimately won her recognition in the United States as well. Despite that acclaim, in 1939 the Daughters of the American Revolution banned her from performing at its Constitution Hall. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt ultimately intervened and facilitated Anderson’s Easter Sunday outdoor concert at the Lincoln Memorial—an event witnessed by 75,000 and broadcast to a radio audience of millions. The affair generated great sympathy for Anderson and became a defining moment in America’s civil rights movement.

Posted: 26 February 2013