“If you want to do something, don’t wait for the masses, because they ain’t coming.”

Christopher Wilson, Director of Experience and Program Design at the National Museum of American History, reflects on the legacy of Civil Rights activist and friend, Franklin McCain. This post was originally published by American History’s blog, “O Say Can You See?”

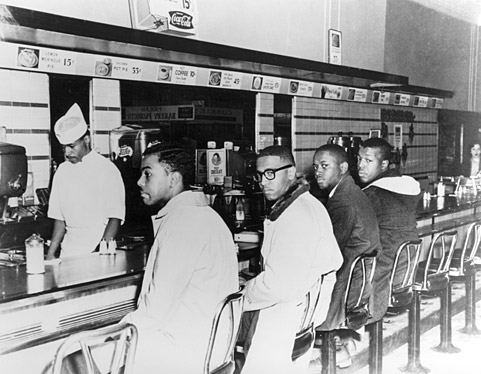

Today our nation has lost a true champion of democracy. Franklin McCain, one of the Greensboro Four, four college students who staged a sit-in at “whites only” lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, on February 1, 1960, has died after a short illness. If our democracy depends on citizens taking an active role in society and working to ensure the nation lives up to the promise of its founding, then there are few better models than Frank.

McCain was born in Union County, North Carolina, in 1942 and grew up in Washington, D.C., before moving to Greensboro to attend North Carolina A&T. Even as a child, McCain had challenged the system of racial segregation he saw all around him by drinking out of both the “white” and “colored” water fountains to see if the taste of the water was different.

On the second day of the Greensboro sit-in, (from left) Joseph A. McNeil and Franklin E. McCain are joined by William Smith and Clarence Henderson at the Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C. (Image courtesy of Greensboro News and Record).

By the time he got to college, he said, “I was angry with a system that led me on and betrayed me, and destroyed most of my faith in a lot of humankind.” His anger, disappointment, and bitterness toward the America in which he lived, however, was directed toward peacefully, nonviolently, and with personal courage and conviction, making the country a better place.

Historian Howard Zinn wrote that “it is hard to overestimate the electrical effect of that first sit-in in Greensboro, as the news reached the nation on television screens, over radios, in newspapers.” Within weeks, thousands of young people were inspired by the action of McCain and his “colleagues” as he called them and soon, as Zinn argued, “for the first time in our history a major social movement, shaking the nation to its bones, is being led by youngsters.” Throughout his life, McCain remained proud of his participation in the movement and claimed he never felt more powerful or confident than while protesting segregation.

This section of the Woolworth’s lunch counter with four stools is on the American History Museum’s second floor.

McCain graduated from A&T in 1964 with degrees in chemistry and biology. The following year he married Bettye Davis, a Bennett College alumna who was a fellow participant in the Greensboro sit-in protests that continued for six months before the F. W. Woolworth lunch counter desegregated. After getting married, McCain he joined the Celanese Corporation in Charlotte as a chemist, where he worked for more than 35 years.

I had the pleasure of knowing Frank for the last ten years and speaking with him often. He visited the museum quite often and was a frequent speaker at our programs, enthusiastically sharing the story of the sit-ins and his advice for young people and all Americans who would like to make a difference and make the world a better place. Frank always told it like it was and did what he felt was right—he was not a man one could corral.

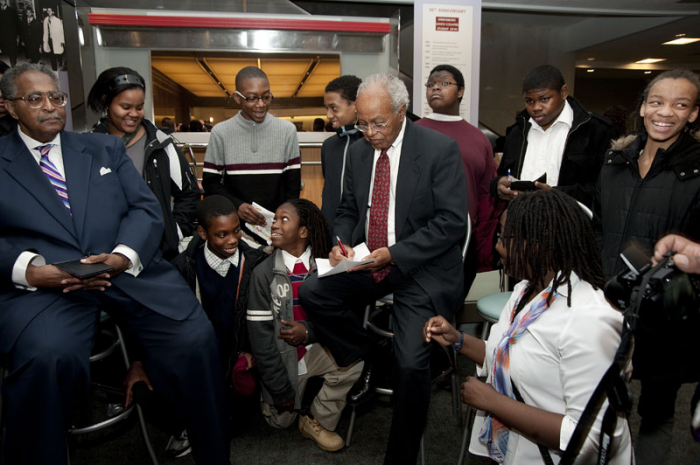

Three surviving members of the Greensboro Four– Jibreel Khazan (formerly Ezell Blair, Jr.), Franklin McCain and Joseph McNeil– participated in an oral history on Feb. 4, 2010.

In 2010, it was my honor to work to present him and the other members of the Greensboro Four with the Smithsonian’s James Smithson Bicentennial Medal. It was fitting that the nation should recognize his contribution to freedom and equality. It was a bit of a challenge, however, trying to shepherd someone with Frank’s spirit from one social engagement to the next, especially when so many young people wanted to shake his hand or take a picture with him. As we went to usher him along, Frank said, “You know, you’re giving us this award because we didn’t follow the rules, right?”

When Frank spoke at the museum in 1995, he stirred the audience with wonderful lessons to take away and live by. “If you are concerned about what is or is not happening today, just reflect on history just a little bit, I’d say.” He spoke of his inspirations, like Ghandi and Mary McCleod Bethune, who made great change at great odds. “History is replete,” he said “with people of that ilk—people who were committed and people who were willing to lay it on the line and do whatever it took” to make a difference. “Don’t wait for the masses,” he said. “I am saying to you the youth, all you have to do is believe, all you have to do is have a dose of commitment, throw yourself to the wind, forget about caution… become the true believer. If you want to do something, don’t wait for the masses, because they ain’t coming.”

Franklin McCain advises that we cannot wait for the approval of others to do something that we know is right in this video:

Christopher Wilson has also blogged about his reflections on the legacy of Nelson Mandela.

Posted: 14 January 2014

- Categories: