How do you dismantle a dinosaur? (Very carefully.)

It’s been just a year since the National Fossil Halls closed for renovation and the last fossils, models, dioramas and paintings have been removed. Find out what’s involved in dismantling these giant specimens as we prepare for an entirely new, bigger and better Fossil Hall coming in 2019.

It’s been just over a year since the National Fossil Halls at the Natural History Museum closed for renovation, and we’ve reached an important landmark: The last fossils have been taken out of the exhibit, and numerous models, dioramas and paintings have been removed as well. Demolition is under way.

The final dinosaur specimens to exit the halls were the tail and hind limbs of Corythosaurus casuarius ) and the full skeleton of Ceratosaurus nasicornis. Both had been exhibited on the wall as “plaque mounts,” with most of the bones partly embedded in plaster. Neither was small enough to pass out of the exhibit intact.

Specimens of Ceratosaurus are rare, and the Smithsonian’s, found in the 1880s, was the very first discovered. Because of its scientific and historical importance, the original bones will be preserved in NMNH’s collections and casts will be made for exhibit in the renovated Fossil Halls.

- The plaque mount of Corythosaurus before it was removed from the wall in the National Fossil Hall at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. (Photo via Digging the Fossil Record, NMNH)

- Sheathed in plywood to protect the fossil from overhead work, the frame holding the Corythosaurus was detached from the wall and lifted onto the floor. (Photo via Digging the Fossil Record, NMNH)

- Preparator Matthew Miller split the plaque carefully, separating the front of the specimen from the back. The halves were small enough to move into storage. (Photo via Digging the Fossil Record, NMNH)

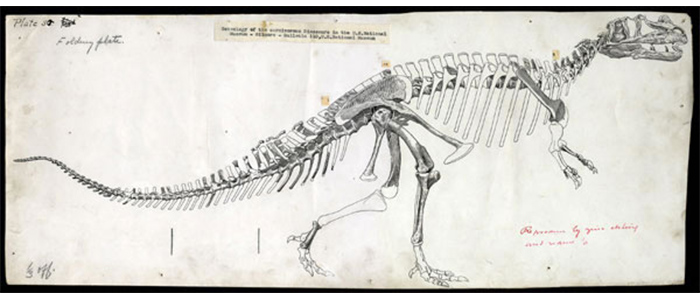

- This 1920 drawing from a scientific publication by Charles W. Gilmore shows the reconstructed skeleton of Ceratosaurus as it was positioned for display. The mount was first exhibited in 1910. (Photo via Digging the Fossil Record, NMNH)

- Preparator Deborah Wagner freed the skeleton of Ceratosaurus from the plaque in sections. (Photo via Digging the Fossil Record. NMNH)

- The empty plaque after the framework was cut and chunks of Ceratosaurus skeleton were extracted from the plaster. (Photo via Digging the Fossil Record, NMNH)

The last mammals to leave the Fossil Halls were Harlan’s ground sloth, Paramylodon harlani and the Stegomastodon arizonae. These large specimens are rotating out of the exhibit lineup and entering storage, where they will be available for scientific study. But first they must be conserved and dismantled, and appropriate archival storage jackets and trays must be built for all of the bones.

- Before the Stegomastodon could be moved, the surrounding exhibit flooring had to be pried away–a dusty job. (Photo via Digging the Fossil Record, NMNH)

- Taking off the ribs: Too large to fit in the elevator, the Stegomastodon skeleton was partly dismantled before removal from the exhibit halls. (Photo via Digging the Fossil Record, NMNH)

- Many hands make less-heavy work. The Harlan’s ground sloth was just small enough to fit through all the doorways between the exhibit and the lab where it would be dismantled. (Photo via Digging the Fossil Record, NMNH)

- The sloth’s arm and hand bones are shown in the new archival storage that is being created for specimens not returning to the renovated exhibit. (Photo via Digging the Fossil Record, NMNH)

- Preparator Alan Zdinak sets up to build a storage jacket for the ground sloth’s pelvis. (Photo via Digging the Fossil Record, NMNH)

Fossils weren’t the only things that needed to make way for the renovation:

A team of art conservators peels a mural off the wall in the Ice Ages Hall. This 1975 painting on canvas by paleoartist Jay Matternes depicts life on the tundra during the Pleistocene. It is part of a set of Matternes’ murals that will be conserved and held in our collections for future use. (Photo via “Digging the Fossil record,” NMNH)

We are keeping many of the models that helped bring the Fossil Halls to life for our visitors, but some models have been given to other museums. The life-sized models of the pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus and Stegosaurus, for example, were trucked to the Museum of the Earth in Ithaca, New York. These models, too, had to be cut into pieces to fit through the doors, so they will have to be reassembled before they can be exhibited.

A version of this post was originally published by Digging the Fossil Record: Paleobiology at the Smithsonian. Read earlier posts about dismantling the Fossil Halls here. The National Fossil Hall is currently closed for renovation. A brand new hall will open to the public in 2019. Dinosaurs are currently on view in the new exhibit The Last American Dinosaurs on the second floor of the National Museum of Natural History.

For more information about the National Fossil Hall renovations or current or upcoming dinosaur exhibits, please visit http://naturalhistory.si.edu/fossil-hall.

Posted: 16 June 2015