Digging the Fossil Record: Paleobiology at the Smithsonian

The Smithsonian has been in the bones business for quite a while. Learn how the accomplishments of a gentleman paleontologist who excavated sites in a coat and tie still resonate within the walls of the Natural History Museum: The Enduring Contributions of James W. Gidley.

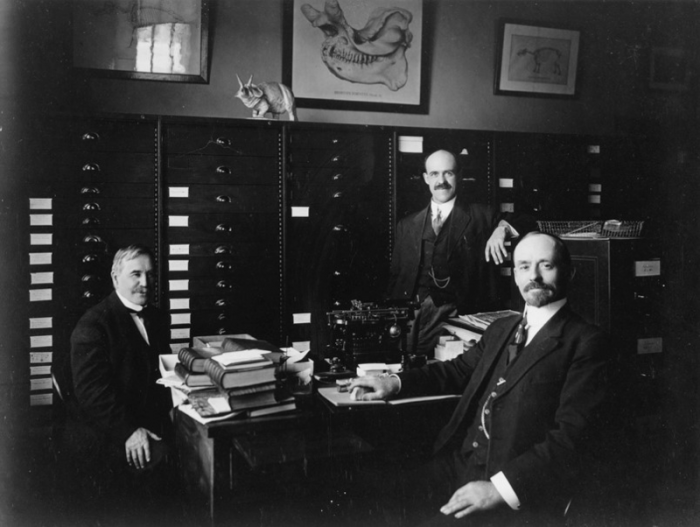

James Williams Gidley (1866-1931) was a vertebrate paleontologist at the United States National Museum, the forerunner of the National Museum of Natural History, during the early 20th Century. He was both a skilled fossil preparator and an active researcher, and his accomplishments in both areas are still felt within the museum’s exhibits and collections. His career is described in a new essay by Department of Paleobiology volunteer Mark Lay, which was adapted for this post, originally published by Digging the Fossil Record: Paleobiology at the Smithsonian.

Dr. Gidley led or co-led approximately 20 field expeditions from the Museum to locations as far flung as Maryland, Montana, Indiana, Nebraska, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Florida. One of the most important was his collection and study of Pleistocene mammals from Cumberland, Maryland.

As the Western Maryland Railroad Company expanded its line west in 1912, workers exposed a small cave system while cutting through limestone rock on the side of Wills Mountain near Cumberland, Maryland. A local resident and amateur fossil collector, Raymond Armbruster, noticed that workmen were carrying fossil bones from the cave as curiosities, and sent a small sample to the USNM for examination. While caves are relatively common, caves containing fossils are not, so Dr. Gidley planned a trip to the site in October 1912. This initial trip resulted in the collection of more than 100 specimens, mostly jaws and jaw fragments from at least 29 different species of mammals, most of which are now extinct. This success was encouraging enough that Gidley and Armbruster collected sporadically at the site for another three years.

- The Cumberland Cave in Maryland, circa 1913. The photo shows the cave entrance, dwarfed by the size of the railroad cut. A tarp and wooden beams mark the opening, which is just left of center at the level of the railroad tracks. (Photo b R. Armbruster)

- James Gidley stands just outside the entrance to the Cumberland Cave in Maryland, circa 1913. (Photo by R. Armbruster)

- The 1913 wardrobe choice of dress shirt and tie is no longer de rigueur at fossil excavations. (Photo by R. Armbruster)

Although the limestone of Wills Mountain is of Devonian age, all the specimens collected from the cave and identified by Gidley are of Pleistocene age, suggesting that, roughly 200,000 years ago, the cave system was connected to the surface for a time by a sinkhole. Based on the probable topography, the sinkhole was approximately 100 feet deep, making it likely that anything that fell in would remain there. The fossils found are a mixture of animals that may have lived in the caves (such as bats, owls and invertebrates), some that may have fallen in, including terrestrial vertebrates (such as wolverines, bears, and peccaries), and numerous plants, all encased in sediments washed in over the years.

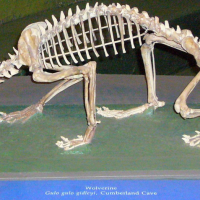

Several exhibit mounts were made from Gidley’s Cumberland Cave fossils. The black bear and wolverine shown below were exhibited in the Ice Ages Hall until recently.

- Black bear (Ursus americanus, USNM 10304) from Cumberland Cave. (Photo by James Di Loreto)

- Wolverine (Gulo gulo, USNM 8175) from Cumberland Cave. (Photo by Mike Brett-Surman)

These mounts are relatively small in size, but Dr. Gidley’s overall impact on exhibits was huge – literally. He supervised the mounting of a whale, Basilosaurus cetoides, the “Indiana Mastodon,” and a large titanothere, Megacerops coloradensis.

Basilosaurus cetoides

Basilosaurus is a genus of Eocene whales that lived about 35-40 million years ago. Our specimen of Basilosaurus cetoides (USNM 4675) is a composite made from the skull and skeletal elements of three individuals collected by Charles Schuchert (Assistant Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology in the USNM) in Alabama in 1894 and 1896. At first, no attempt was made to reassemble the skeleton into a life-like pose, but after Frederic Lucas (Curator in the Division of Comparative Anatomy in the USNM) published a partial description of the whale’s anatomy in 1901 it became possible to consider creating a true restoration. Dr. Gidley was responsible for directing the creation of the mounted specimen, and the work was completed in 1912. This was the first mount of a Basilosaurus ever done. It measured in at approximately 55 feet long and was given a prime spot, shown below, in the Hall of Extinct Monsters.

Gidley’s mount of Basilosaurus cetoides (USNM 4675) as it was first displayed in the Hall of Extinct Monsters. (Photo courtesy of Smithsonian Archives)

The mount survived essentially “as is” until 1989, when it was given some anatomical corrections and repairs and moved into the “Life in the Ancient Seas” exhibit (below, left). Then, in 2008, it was remounted in a new pose on a modern armature. The hind limbs were replaced with cast bones from another specimen, and the skeleton was moved to the Sant Ocean Hall (below, right), where it can be seen today. It remains the only real mounted Basilosaurus specimen on display in the world.

- Basilosaurus cetoides (Photo by Chip Clark)

- Basilosaurus cetoides (Photo by Chip Clark)

Indiana Mastodon

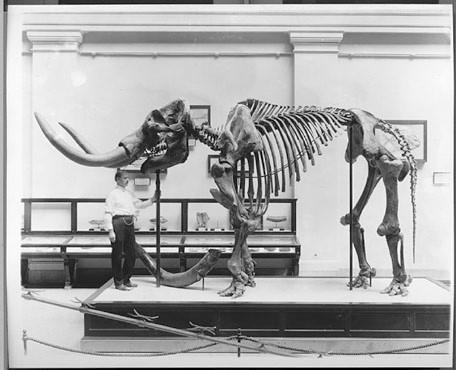

Most of the American mastodons (Mammut americanum) found in this country are fragmentary. Complete (or relatively complete) skulls and skeletons are rare. One of those rare finds was reported to the USNM in 1914. On October 30th, George P. Merrill, Head Curator of Geology, wrote to the Assistant Secretary that “Mr. W. D. Pattison, a druggist of Winamac, Indiana, called at the office a few days ago and stated that in the work of ditching on some of his property in Indiana they had found a Mastodon skeleton, evidently in a good state of preservation; that they had removed only portions of the skull and one limb bone, which they would donate to us if we wished, and also give us the privilege of exhuming the entire skeleton.” The Museum paid for the bones to be shipped to Washington, where James Gidley examined them. Gidley reported to Merrill that, “the specimen… consist(s) of finely preserved portions of… an unusually large individual and with a minimum amount of preparation would make an attractive exhibit.” He went on to describe where a mount of such size could fit within the existing exhibit hall, concluding, “If, therefore, funds should become available at any time in the reasonably near future, I believe it would be well worth while accepting Mr. Pattison’s offer to exhume the remaining parts.” Funds must have been forthcoming because Gidley made two trips in 1915 to excavate and remove the rest of the specimen. The nearly complete skeleton (USNM 8204) required only limited restoration (done under Gidley’s direction) and the mount was put on display in 1916.

James Gidley stands with the newly mounted “Indiana Mastodon” (Mammut americanum, USNM 8204) in the Hall of Extinct Monsters. (Photo courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives)

Megacerops coloradensis

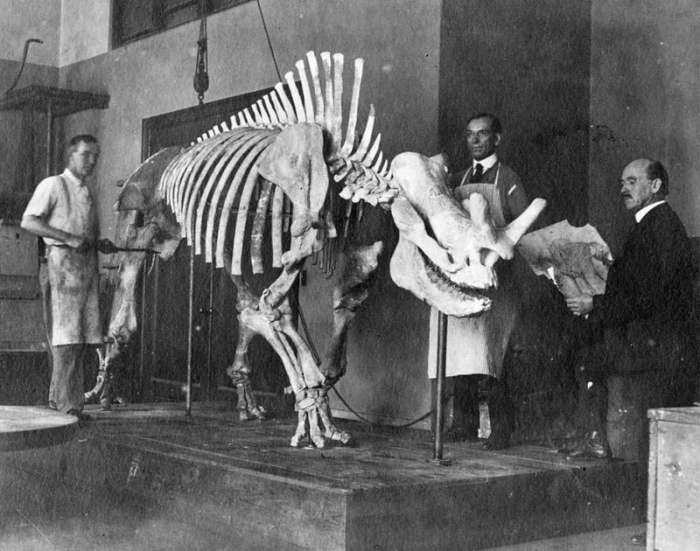

A photograph (below) from our archives suggests that Gidley also supervised the creation of a third large display mount, that of Megacerops coloradensis (USNM 4262, this specimen had been excavated in Nebraska by John Bell Hatcher in 1887 and identified previously as Brontotherium hatcheri.) Dated 1919, the photo shows Gidley posed at the head of the mount with a sketch of the animal in his hands. Two men in work aprons, presumably Thomas Horne, who is known to have built the mount, and a helper, believed to be John Barrett, stand to either side of the skeleton. The Museums Annual Report of 1920 trumpeted both the skill involved in creating the mount and that, “this imposing addition [to the exhibits] … is the first and only mount to the genus to be exhibited.”

At work on the mount of Megacerops coloradensis (USNM 4262), a large Eocene herbivore. (Photo courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives)

The museum has always been justifiably proud of the many unique fossil specimens exhibited in its halls, and through the work of Gidley and others during the early decades of the 20th Century the number of these important mounts rose substantially. But with time they have become outdated. The mastodon and Megacerops, along with many other exhibit specimens, were disassembled recently as part of our ongoing National Fossil Hall renovations. After their bones have been conserved, they will be remounted on modern armatures and positioned in new stances that reflect 100 years of advancement in our scientific understanding of how these animals stood and moved. We have no doubt that James Gidley would approve of these changes to his century-old work.

Read more about the history of the Department of Paleobiology at the National Museum of Natural History, our collections and exhibits here.

Posted: 3 August 2015

-

Categories:

Feature Stories , Natural History Museum , Science and Nature