The Renwick Gallery reopens with a renewed sense of “WONDER”

The venerable Renwick Gallery has reopened in its third iteration in three centuries. In celebration of its enduring impact on American art and craft, nine artists have created nine awe-inspiring works that draw on the unchanging power of the natural world for their inspiration.

Gabriel Dawe, Plexus A1, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Courtesy Conduit Gallery

Photos by Ron Blunt

An intersecting prism of light arcs overhead—made of thousands of strands of thread. A massive hemlock tree hovers above the floor, occupying an equally massive gallery from portal to portal. The Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, rendered in shining marbles, meander across the floor and up the walls of its space.

Walk into the newly renovated Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the debut exhibition there grabs the mind and does not let go.

“Wonder,” which features nine artists’ interpretations of experiences that create awe, opened Nov. 13 in the revamped space, whose updates, including new windows and all-new LED lighting, are expected to save the building 70 percent in energy costs over the next several years.

By complete coincidence, all of the works draw from nature for their inspiration. The artists walked through the building while it was still empty to help direct their creativity, Nicholas Bell, curator of the “Wonder” exhibition, points out. The artists all worked toward nature in their own way, but were not directed to do so.

The artists were chosen for their sensitivity to architectural space, their passion for making, and an intense attentiveness to what surrounds them, Bell continues. The exhibition turns the Renwick’s mission to show the work of artisans and craftsmen on its head by inviting the finished works to dominate the galleries. Yet every object in the museum is as painstakingly fashioned as any smaller work of craft.

“When people come to the Renwick, they come to ponder what it means to be skilled, to value labor and process in an age when a lot of that information has been forgotten,” Bell said. “And here we see regular objects, things you’re used to, but out of context and filtered through the artists’ genius.”

“It says that people are really concerned and interested in what’s going on in the world,” Bell said. “The artists looked to the natural world. That’s where they find wonder for themselves. When you come here, it refreshes your eyes, so when you go back outside, you have the potential to see the world differently.”

The artists

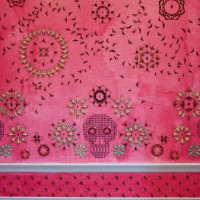

Jennifer Angus

born Edmonton, Canada 1961; resides Madison, Wisc.

In the Midnight Garden, 2015

cochineal, various insects, and mixed media

Angus’s genius is the embrace of what is wholly natural, if unexpected. Yes, the insects are real, and no, she has not altered them in any way except to position their wings and legs. The species in this gallery are not endangered, but in fact are quite abundant, primarily in Malaysia, Thailand, and Papua New Guinea, a corner of the world where Nature seems to play with greater freedom. The pink wash is derived from the cochineal insect living on cacti in Mexico, where it has long been prized as the best source of the color red. By altering the context in which we encounter such species, Angus startles us into recognition of what has always been a part of our world.

The Renwick will soon host a tour of In the Midnight Garden hosted by an entomologist from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History to examine the space Angus created: four walls of natural wallpaper-like designs, made entirely from the bodies of insects.

-

Jennifer Angus, In the Midnight Garden, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Jennifer Angus, In the Midnight Garden, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Jennifer Angus, In the Midnight Garden, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Jennifer Angus, In the Midnight Garden, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Jennifer Angus, In the Midnight Garden, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

Chakaia Booker

born Newark, N.J. 1953; resides New York City

ANONYMOUS DONOR, 2015

rubber tires and stainless steel

Booker was inspired to explore tires as a material while walking the streets of New York in the 1980s, when retreads and melted pools of rubber from car fires littered the urban landscape. By massing, slashing, and reworking a material we see daily yet never fully consider, she jolts us out of complacency to grasp these materials for what they are: a natural resource marshaled through astonishingly complex channels into a product of great convenience and superabundance.

-

Chakaia Booker, ANONYMOUS DONOR, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Chakaia Booker, ANONYMOUS DONOR, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Chakaia Booker, ANONYMOUS DONOR, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Chakaia Booker, ANONYMOUS DONOR, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

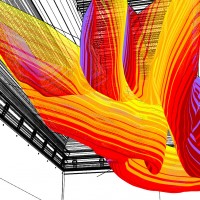

Gabriel Dawe

born Mexico City, Mexico 1973; resides Dallas, Texas

Plexus A1, 2015

thread, wood, hooks, and steel

Dawe’s architecturally scaled weavings are often mistaken for fleeting rays of light. It is an appropriate trick of the eye, as the artist was inspired to use thread in this fashion by memories of the skies above Mexico City and East Texas, his childhood and current homes, respectively. The material and vivid colors also recall the embroideries everywhere in production during Dawe’s upbringing.

-

Gabriel Dawe, Plexus A1, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Courtesy Conduit Gallery

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Gabriel Dawe, Plexus A1, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Courtesy Conduit Gallery

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Gabriel Dawe, Plexus A1, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Courtesy Conduit Gallery

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Gabriel Dawe, Plexus A1, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Courtesy Conduit Gallery

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Gabriel Dawe, Plexus A1, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Courtesy Conduit Gallery

Photos by Ron Blunt

Tara Donovan

born New York City 1969; resides New York City

Untitled, 2014

styrene index cards, metal, wood, paint, and glue

Employing mundane materials such as toothpicks, straws, Styrofoam cups, scotch tape, and index cards, Donovan gathers up the things we think we know, transforming the familiar into the unrecognizable through overwhelming accumulation. The resulting enigmatic landscapes force us to wonder just what it is we are looking at and how to respond. The mystery, and the potential for any material in her hands to capture it, prompts us to pay better attention to our surroundings, permitting the everyday to catch us up again.

-

Tara Donovan, Untitled, 2014

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

© Tara Donovan, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Tara Donovan, Untitled, 2014

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

© Tara Donovan, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Tara Donovan, Untitled, 2014

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

© Tara Donovan, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Tara Donovan, Untitled, 2014

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

© Tara Donovan, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Tara Donovan, Untitled, 2014

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

© Tara Donovan, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Photos by Ron Blunt

Patrick Dougherty

born Oklahoma City, Okla.1945; resides Chapel Hill, N.C.

Shindig, 2015

willow saplings

Dougherty has crisscrossed the world weaving sticks into marvelous architectures. Each structure is unique, an improvised response to its surroundings, as reliant on the materials at hand as the artist’s wishes: the branches tell him which way they want to bend. This give and take lends vitality to Dougherty’s work, so that walls and spires are a record of gestures and wills. Finding the right sticks remains a constant challenge, and part of the adventure of the art-making sends him scouring over the forgotten corners of land where plants grow wild and full of possibility.

-

Patrick Dougherty, Shindig, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Patrick Dougherty, Shindig, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Patrick Dougherty, Shindig, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Patrick Dougherty, Shindig, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Patrick Dougherty, Shindig, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

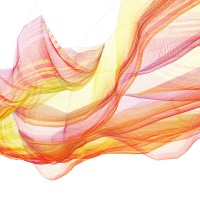

Janet Echelman

born Tampa, Fla. 1966; resides Brookline, Mass.

1.8, 2015

knotted and braided fiber with programmable lighting and wind movement above printed textile flooring

Echelman’s woven sculpture corresponds to a map of the energy released across the Pacific Ocean during the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, one of the most devastating natural disasters in recorded history. The event was so powerful it shifted the earth on its axis and shortened the day, March 11, 2011, by 1.8 millionths of a second, lending this work its title. Waves taller than the 100-foot length of this gallery ravaged the west coast of Japan, reminding us that what is wondrous can equally be dangerous.

-

Janet Echelman, 1.8, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Courtesy of Janet Echelman, Inc.

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Janet Echelman, 1.8, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Courtesy of Janet Echelman, Inc.

Photos by Ron Blunt

John Grade

born Minneapolis, Minn. 1970; resides Seattle, Wash.

Middle Fork (Cascades), 2015

reclaimed old-growth western red cedar

To commemorate the Renwick’s reopening, Grade selected a hemlock tree in the Cascade Mountains east of Seattle that is approximately 150 years old—the same age as this building. His team created a full plaster cast of the tree (without harming it), then used the cast as a mold to build a new tree out of a half-million segments of reclaimed cedar. Hundreds of volunteers assisted Grade, hand carving each piece to match the contours of the original tree. After the exhibition closes, Middle Fork (Cascades) will be

carried back to the hemlock’s location and left on the forest floor, where it will gradually return to the earth. Grade’s second tree, Middle Fork (Arctic), is on view downstairs in the Palm Court.

Middle Fork (Arctic), 2015

Shortly after completing Middle Fork (Cascades)—the larger of his two trees, on view upstairs— Grade traveled to northern Alaska, where he was dropped by bush plane at the fringes of the tree line to search for the elusive balsam poplar. After several days’ travel by raft and foot, he located and cast a specimen using the same technique as for the Cascades hemlock. Astonishingly, given its stunted size, the balsam poplar used as a model is the same age as the hemlock re-created upstairs, about 150 years old. The difference in its scale is attributable to the harsh climate in the rocky plains just below the Beaufort Sea.John Grade

-

John Grade, Middle Fork, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

John Grade, Middle Fork, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

John Grade, Middle Fork, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

John Grade, Middle Fork, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

John Grade, Middle Fork, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

John Grade, Middle Fork, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

Maya Lin

born Athens, Ohio 1959; resides New York City

Folding the Chesapeake, 2015

marbles and adhesive

Architect and artist Maya Lin, perhaps most famous for her winning design of the Vietnam War Memorial while still a college student at Yale, brought the Chesapeake Bay indoors, recreating it from thousands of translucent marbles affixed to the floor and walls. Creeping up the walls and around the windows, its far-reaching tendrils show just how broad the reach of the estuary and its tributaries is, an impact difficult to represent on a mere map.

Growing up in Ohio in the 1960s, Lin watched her father participate in the fledgling studio glass movement then gathering steam in nearby Toledo. The marbles used in this installation are the same industrial fiberglass product Henry Huan Lin and other glass-blowing pioneers experimented with then, which were soon abandoned by artists as technical knowledge matured. Folding the Chesapeake marks their first use by Maya Lin and a new chapter in her decades-long investigation of natural wonders. By shaping rivers, fields, canyons, and mountains within the museum, Lin shifts our attention to their outdoor counterparts, sharpening our focus on the need for their conservation.

-

Maya Lin, Folding the Chesapeake, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photo copyright Stephanie Sinclair

-

Maya Lin, Folding the Chesapeake, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Maya Lin, Folding the Chesapeake, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Maya Lin, Folding the Chesapeake, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Maya Lin, Folding the Chesapeake, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Maya Lin, Folding the Chesapeake, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Maya Lin, Folding the Chesapeake, 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photos by Ron Blunt

Leo Villareal

born Albuquerque, N.M. 1967; resides New York City

Volume (Renwick), 2015

white LEDs, mirror-finished stainless steel, custom software, and electrical hardware

Only part of Villareal’s artwork is visible in the materials suspended above the staircase. This hardware serves primarily as a vehicle for the visual manifestation of code—an artist-written algorithm employing the binary system of 1s and 0s telling each LED when to turn on or off. This simple command creates lighting sequences that will never repeat exactly as before. It also changes how we think of code, from a line of characters that can be read on any screen to an object that must be witnessed in the museum.

-

Leo Villareal, Volume (Renwick), 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

© Leo Villareal, courtesy CONNERSMITH

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Leo Villareal, Volume (Renwick), 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

© Leo Villareal, courtesy CONNERSMITH

Photos by Ron Blunt

-

Leo Villareal programming Volume (Renwick), 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

© Leo Villareal, courtesy CONNERSMITH

-

Leo Villareal programming Volume (Renwick), 2015

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

© Leo Villareal, courtesy CONNERSMITH

Though most of the installations will move on by mid-2016, Leo Villareal’s glittery suspended sculpture, composed of 23,000 LEDs pulsating in a perpetual random pattern, will become a permanent addition to the Renwick, said Betsy Broun, The Margaret and Terry Stent Director, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Broun also noted that the decision to annotate the engraved inscription above the Renwick’s entryway, “Dedicated To (the future of) Art”, is a fun-spirited and enthusiastic nod to the innovations that the present and future bring to what it means to be a craftsman in the 21st century.

“We’re not turning our backs on the digital age; many artists couldn’t be here without it,” Broun said. “But what the eye and hand do, together with what the mind and computer do, combine to create something wondrous, and that validates us as human beings.

“Now here we are [re]opening for the third time in three centuries,” Broun continued. As that dawns on us, we need to understand that it’s [the renovation] something more than updated windows and air conditioning. When we think about the inscription chipped in stone above the front door, it’s also about encouraging American genius. We’re rethinking what a crafts museum is in the 21st century.”

The renovation

The Renwick Gallery was one of the first buildings in America designed specifically to be an art museum and is considered one of the first and finest examples of Second Empire Architecure in the country. James Renwick Jr. designed the building in 1859 to display William Wilson Corcoran’s art collection, taking inspiration from the new pavilions of the Louvre in Paris. When the building first opened a decade after the Civil War it was hailed as the ‘American Louvre,’ symbolizing the young nation’s aspirations for a distinctive culture. It was saved from demolition by Jackie Kennedy in 1962 and subsequently designated a National Historic Landmark. The Smithsonian American Art Museum has used the building since 1972 to present a program of traditional and modern crafts, decorative arts and architectural design. The opening marks the third time that the building has opened as an art museum in three centuries (1874, 1972, 2015). Read an in-depth history of the Renwick Gallery here.

This project marks the first comprehensive renovation to the building in 45 years. Westlake Reed Leskosky is the lead architectural design and engineering firm, and Consigli Construction Co. Inc. is the general construction contractor. Both firms are recognized leaders in working with museums and historic buildings.

A dramatic new carpet for the Grand Staircase, designed by French architect Odile Decq in her signature red color, re-establishes the French influence in the building. Further enhancing the new, contemporary look of public spaces are a lighter paint palette in the galleries, custom-designed furnishings for the lobby by metalsmith Marc Mairoana, LED up-lighting of the ceiling coves and gilding on decorative moldings.

The renovation of this National Historic Landmark has revealed two long-concealed ceiling vaults on the second floor, restored the original 19th-century window configuration throughout and repaired original moldings and other decorative features, in addition to numerous other preservation efforts. Infrastructure has been replaced or upgraded with the most up-to-date sustainable and energy-efficient technologies.

Public and gallery spaces are now illuminated entirely with LED lighting. The new lighting system is a landmark advance in museum energy efficiency and, combined with other infrastructure improvements, will reduce the building’s energy usage by more than 70 percent, making the Renwick Gallery one of the most energy efficient Smithsonian museums. Read more in-depth details about the renovation here.

Learn how David Gleeson and his design team at SAAM took a decidedly modern approach to historic preservation: “Everything is pared back, cleaner, and brighter and lighter,” Gleeson says. “All of the architectural elements are still there, and highlighted. But it’s going to be a lot easier to enjoy the artwork with this pared-back, minimalist approach.” How subtle presentation enhances art’s power.

- Front exterior of the renovated Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American Art. (Photo by Ron Blunt)

- Artist Leo Villareal’s installation above the Grand Staircase of the renovated Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian’s American Art Museum. (Photo by Ron Blunt)

- A rug by Odile Decq graces the stairs to the Nancy Brown Negley Hall at the renovated Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian’s American Art Museum. (Photo by Ron Blunt)

- The Octogan Room with a chandelier by Dale Chihuly and Hiram Powers’ “The Greek Slave” in the renovated Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian’s American Art Museum. (Photo by Ron Blunt)

- Detail of the new palette and gilding in the interior of the renovated Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian’s American Art Museum. (Photo by Ron Blunt)

- The new palette and gilding in the interior of the renovated Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian’s American Art Museum. (Photo by Ron Blunt)

This post was compiled from staff reports and original reporting by Michelle Donohue.

Posted: 24 November 2015

-

Categories:

American Art Museum , Art and Design , Collaboration , Feature Stories , News & Announcements , Renwick Gallery

[…] Read more about the Renwick’s most recent renovation and spectacular opening exhibition. The Renwick Gallery reopens with a renews sense of WONDER […]