Access + Ability: Designing with people, not for them

Secretary Skorton examines some of the ways we are working to include people of all abilities in the Smithsonian experience.

My morning routine is fairly simple: I enter the east door of the Smithsonian Castle, climb a flight of stairs to my office, log onto the computer, and check my email and schedule to begin the day. But for someone without the strength to push open those heavy doors, the mobility to climb stairs, the dexterity to manipulate a mouse or the ability to see a computer screen, these mundane tasks present almost insurmountable barriers.

I was inspired to write about accessibility and inclusion this month by the thought-provoking new exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York. “Access+Ability” was inspired in part by an Institution-wide effort to expand public accessibility to our collections and programs.

Prosethetic Leg Cover, ca. 2011, designed by McCauley Wanner and Ryan Palibroda. These prosthetic leg covers adorn and add a human silhouette to artificial limbs. Intended as a fashion accessory, the goal is to give amputees choice to select from a large variety of colors and patterns and the ability to shop in the same way they choose clothes.

The exhibition features more than 70 innovative designs developed with and by people with a wide range of physical, cognitive, and sensory abilities. From low-tech products that assist with daily routines to the newest technologies, the exhibition explores how users and designers are expanding and adapting accessible products and solutions in ways previously unimaginable.

Many of the objects on display are evolved versions of their former selves, still recognizable as assistive devices, but elevated into elegant accessories. From increasingly versatile canes and customized prosthetic leg covers to shirts with magnetic closures and shoes with wrap-around zipper systems, the exhibition shows how products created in the last decade are becoming more accessible, functional, and fashionable all at the same time.

Maptic (Tactile Navigation System for the Visually Impaired), 2017, designed by Emilios Farrington-Amas. Necklace and bracelets are a wearable navigation system for people who are blind. Connected to a voice-controlled iPhone app and GPS, haptic vibrations not only guide the wearer, but also are able to track obstacles above the knee.

Motivation Rough Terrain Wheelchair, 2005. This wheelchair navigates rough, unpaved, and uneven terrain, specifically in the developing world where the ground may be mud or sand. The three rather than four wheels provide extra Access+Ability stability when pushing, propelling, and even tipping around obstacles.

In 2017, Cooper Hewitt committed itself to a campus-wide effort to broaden audiences and ensure the museum is even more welcoming to all. The museum partners with key individuals and organizations and uses its galleries, programming, and online resources to raise awareness of accessible design innovation; inspire dialogue; and promote problem-solving in support of inclusivity. For example, the museum recently partnered with the New York City Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities to host a 10-day lab using gallery space for experimentation and discussion around accessibility. One workshop focused on access and inclusion for college students and showcased student projects. “The lab was very successful,” says Caroline Baumann, Cooper Hewitt’s director. “It is very encouraging that so many students are focusing on the area of accessibility. We decided to exhibit their innovative solutions and ideas on the ground floor of the museum.”

In February, Cooper Hewitt presented Cooper Hewitt Lab: Design Access, 12 days of free programming to raise awareness off accessible design, including a workshop for college students.

Photo © 2017 Scott Rudd

The innovative designs created by college students during Cooper Hewitt Lab: Design Access in February are showcased on the museum’s first floor.

“Accessibility and Inclusivity is or should be a primary goal for all organizations and leaders today,” Caroline continues. “Cooper Hewitt needs to be a leader in this conversation and movement, and encourage this spirit of inclusivity. We want to emphasize what people can do, not what they cannot do. Life is about design or the absence of design and it’s horrible if the interfaces are incomplete. We are raising awareness around making life experiences more accessible to all. We need to design with people, not for them. Don’t design for age, design for ability levels.”

Visitors on the autism spectrum who might be sensitive to flashing lights or noise; people who have hearing loss; persons with traumatic and other brain-based disabilities, including dementia; wheelchair users; people who learn best through tactile experiences; people who have vision loss: are they being served? If not, what can we do to make sure the Smithsonian’s resources and experiences are accessible to everyone?

In February, Cooper Hewitt presented Cooper Hewitt Lab: Design Access, 12 days of free programming to raise awareness off accessible design, including a program designed especially for teens.

Photo © 2017 Scott Rudd

Access Smithsonian (formerly the Smithsonian’s Accessibility Program) works to ensure the broadest inclusion, in part by implementing Smithsonian Directive 215, which covers accessibility for people with disabilities, including visitors, staff, interns, volunteers, fellows—anyone associated with the Smithsonian community. Director Beth Ziebarth and Program Specialist Ashley Grady create practices and guidelines on such things as the use of service animals, but also work in concert with museums and other Smithsonian organizations on facility design, exhibition design, and programming.

Access Smithsonian also does a significant amount of training for Smithsonian staff about accessibility and disability. This can include everything from training new security officers who will interact with visitors to working with exhibition designers on how to introduce tactile elements and technology to a new exhibition. Access Smithsonian also works directly with individuals in the disability community as well as groups such as the American Association of People with Disabilities; with other cultural arts institutions such as the Kennedy Center; and with organizations such as the HSC Foundation (a parent organization that supports different levels and stages of care for people with disabilities) to identify opportunities to better serve the community.

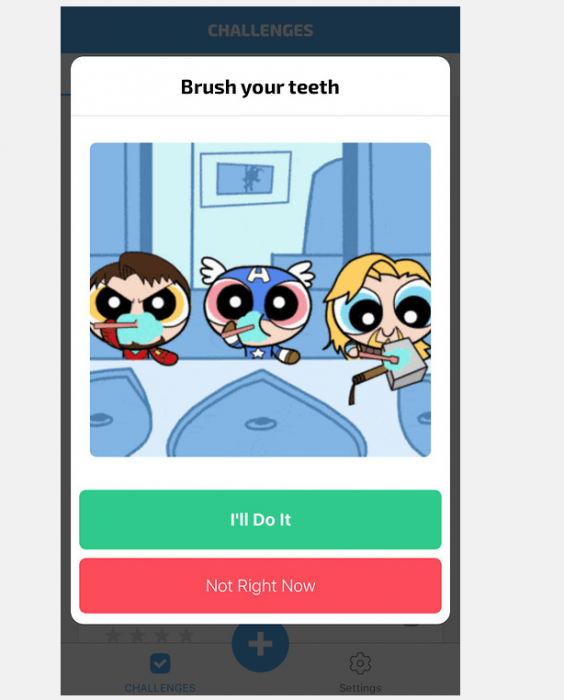

LOLA (Laugh Out Loud Aid) app, designed by Tech Kids Unlimited, 2015. The LOLA Laugh Out Loud Aid) app is designed to engage children on the autism spectrum using humor as a tool to help train their brain and acquire different social and daily living skills.

“One of the benefits of a centralized accessibility office is that we can look at the Smithsonian as a whole to make sure we are offering consistent accessibility for people with disabilities,” Beth explains. “If we see a real variation among the museums, that’s problematic. If a family with a child who has a sensory processing disorder comes to the Smithsonian, they want to know they can access all of the Smithsonian equally—the dinosaurs, the pandas, the planes, everything.”

“Inclusion and diversity are two very important tenets of who we are as an institution,” says Ashley, a former special education teacher. “A lot of Smithsonian staff are very passionate about accessibility, about making sure that programs and facilities and content of the museums are accessible to all.”

In February, Cooper Hewitt presented Cooper Hewitt Lab: Design Access, 12 days of free programming to raise awareness off accessible design, including the symposium “Designing Accessible Cities.”

Photo © 2017 Scott Rudd

Access Smithsonian’s Morning at the Museum program continues to expand as Ashley and Beth train peers across the Institution. During Morning at the Museum, a museum opens early for families of children who may benefit from reduced crowds, shorter wait times, less noise, and other factors. Staff and volunteers offer accommodations such as noise-cancelling headphones, touchable objects, quiet spaces, sensory maps, picture schedules, and other supports to help guests ranging in age, ability, and learning styles enjoy a less stressful museum visit. Since its pilot in 2011 at the American History Museum, the program has grown: from six Mornings in 2015 to more than 25 that will be held this year. I had the privilege of participating in a recent Morning at the Museum at the National Museum of African American History and Culture and was inspired, moved and impressed by what I saw.

A child wearing noise reduction headphones enjoys the aquarium during a recent Morning at the Museum program at the National Museum of Natural History. (Photo by Jaclyn Nash)

The Smithsonian Accessibility Network (SAN) was established last year as a way to share best practices to meet the needs of a diverse public. Headed by Julia Garcia, exhibit developer at the American History Museum, and Devra Wexler, an exhibit developer at the Zoo, SAN has held several meetings to share ideas and techniques.

“We think about SAN as a marketplace of ideas,” says Brooke Rosenblatt, visitor experience manager at the Freer and Sackler Galleries. “Each time one of us wants to start a new initiative, we don’t have to reinvent the wheel because our colleagues at another museum have probably done something similar.”

While FSG was closed for renovations, staff across departments had a chance to think about accessibility in new ways, says Brooke, who leads the accessibility task force for the galleries. When the museums reopened last October, some innovations included label sets with larger print, movie clips that indicate there is no narration (to assure a visitor with hearing loss that she is not missing out on any information), a lower information desk that is more accessible for children or visitors using wheelchairs, and lightweight folding stools that visitors can opt to carry with them throughout the exhibition rooms in order to take a break.

A young visitor enjoys a recent Morning at the Museum program at the National Museum of Natural History. (Photo by Jaclyn Nash)

When it comes to enhancing accessibility, no idea is too bold, says Devra. The Zoo offers “Take a Break” spaces at events such as “Boo at the Zoo” that offer many types of sensory objects for families to use, including headphones, body socks, weighted blankets, and koosh balls, that can help calm visitors who may become overstimulated.

Among other projects under consideration are improved ramp access, signage that includes raised text and Braille, objects that can be touched, incorporating visual and auditory elements, and additional ways to increase equal access.

The Zoo’s unique topography and campus layout present both challenges and opportunities in terms of expanding the boundaries of what accessibility can mean. Primates keeper Melba Brown, who assists with the Morning at the Museum program at the Zoo, has written “social narratives”—step-by-step breakdowns, in words and pictures, of what a child might expect on a visit—for the Small Mammal House, Great Ape House, Lemur Island, Think Tank, Gibbon Ridge and Amazonia, with a Zoo-wide narrative map in the works.

I cannot possibly enumerate all the ways we are working toward inclusivity, but these and other initiatives truly represent the spirit of One Smithsonian. I am inspired by the empathy and enthusiasm of our community and by the surging groundswell of support across the Smithsonian for greater inclusiveness and accessibility for people of all abilities.

Editor’s note: The Friends of the National Zoo’s education team played the lead role in developing the ‘social stories’ noted in the article. FONZ secured the funding, wrote and/or rewrote the stories using Melba Browns’s outlines, assured they were 508-compliant, made sure photo releases were secured, and translated them into Spanish. FONZ was also instrumental in developing ‘quiet spaces’ at Zoo events. We regret the omission.

Posted: 12 March 2018