A shared history, a human story

NMAAHC’s Mary Elliott brings grace and gravity to her work helping museum visitors broaden their understanding of the causes and consequences of slavery.

Mary Elliott (Photo by Amy Rogers Nazarov)

Weaving her way through a large, hushed crowd of museum attendees moving slowly through the Slavery & Freedom exhibit she helped bring to life, Mary Elliott reiterates the guiding theme of the gallery.

“We view the American story through the African American lens. During the period of slavery that lens looked out onto a diverse world that included enslaved Africans, free people of color, Native Americans, poor whites, yeoman white farmers and the planter elite.” says Elliott, a museum specialist at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture. “The history of this nation is our shared history.”

As Elliott quietly describes to a visitor the items on view, numerous guests drift her way to listen and ask questions, which she fields with patience and scholarship.

Wrought iron slave collar with a three inch locking device and a three inch key. The collar is made up of two pieces of iron attached with a hinged, chain link back. Each end of the collar has an eyelet that can overlap and the lock can be inserted in to. The lock has a cylinder locking mechanism and a curved shackle hinged on one side. The key has an eyelet on one end and a shoulder in the middle of the shaft. The teeth of the key are threaded like a screw. (Courtesy National Museum of African American History and Culture)

Recently elected to serve on the governing board of the American Historical Association, this former attorney found that genealogy and independent history research served as a springboard for a museum career. Elliott traced her family’s roots from their enslavement in Mississippi through Reconstruction to their migration to Indian Territory (which later became the state of Oklahoma). Landowners, entrepreneurs, educators and civic and community leaders, Elliott’s forebears out west (some of whose photos are on display in this exhibit) were among those working to secure a place for black Americans in the young country.

There is little greater satisfaction than knowing her work on Slavery & Freedom– along with that of co-curator Nancy Bercaw (now at the National Museum of American History), and of numerous NMAAHC staff – is spurring transformative conversations among museumgoers of all races, ages and backgrounds. Here visitors reflect on the scourge of slavery, its economic, political and cultural legacies and what it teaches us about human resilience.

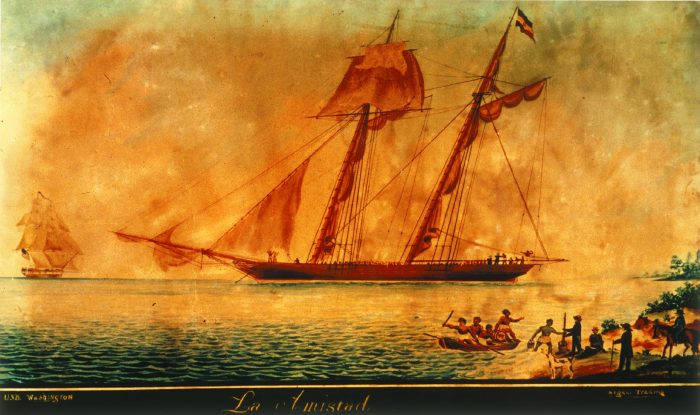

The schooner Clotilda was the last known U.S. slave ship to bring captives from Africa to the United States, arriving at Mobile Bay in autumn 1859 (some sources give the date as July 9, 1860), with 110-160 slaves. The ship was a two-masted schooner, 86 feet long with a beam of 23 feet, similar to this painting of La Amistad. Clotilda was burned and scuttled at Mobile Bay.

This is a contemporary painting of the sailing vessel La Amistad off Culloden Point, Long Island, New York, on 26 August 1839; on the left the USS Washington of the US Navy (courtesy New Haven Colony Historical Society and Adams National Historic Site)

Elliott recently returned from a trip to Alabama where she was part of a team from the museum called on by the Alabama Historical Commission. The Slave Wrecks Project team was tapped to consult on the site of a potential key discovery: the remains of the slave ship Clotilda, the last known such ship to arrive (in 1859) in the States. The SWP, hosted by NMAAHC, researches, preserves and shares the history of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, primarily using maritime archaeology.

While it was later established by the Slave Wrecks Project and partner organizations that the wreckage was likely not the Clotilda after all, Elliott’s time on the ground yielded its own treasures. She engaged with the community of descendants of the African captives held on the Clotilda who established the community known as Africatown in Mobile, Ala. She also served as a liaison between the residents, historians, legislators and others who would like to see the neighborhood’s historic and cultural relevance developed in as-yet-undetermined ways.

Africatown residents have struggled with community blight and with environmental issues brought on by industrial encroachment. State and local collaborators are working with community organizations to draw attention to what happens to the historic community and to help with its preservation and revitalization. Even as the wreck of the Clotilda remains elusive, the fact that the desire for the search to continue underscores the historic value of the region. It elevates the importance of ensuring that the community residents have a voice as to what will become of Africatown and that they are positioned to benefit from growing recognition of its place in history.

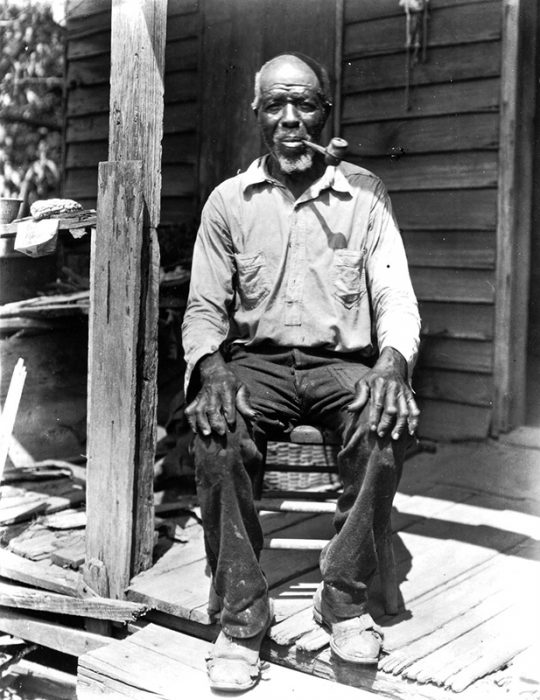

Cudjo Lewis (ca. 1841-1935) was a founder of African Town (now Africatown) in Mobile, Alabama, and was the last survivor of the Clotilda, the last ship to illegally transport captive Africans to the United States. Toward the end of his life, Lewis became famous when his story was published in a book and newspapers. (Photo courtesy Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama)

Elliott said she expects to return to the area with SWP team members to continue to engage in the effort to bring forward the story of Africatown and illuminate its importance in the American story and the American landscape.

She surveys the diverse crowd of guests studying shackles sized for adults and for children, a wall with the names of some of the thousands of ships that carried captive Africans across the Atlantic and the cabin that once housed enslaved African American men, women and children. Observing their expressions, she notes that she continually mulls new ways to bring the exhibition content to life and to extend it beyond the walls of the museum.

“I appreciate that our visitors give each other space to wrestle with this history,” she says. That they are doing so “means we’ve done what we needed to do, and that [visitors] are taking ownership of this as a shared history, as a human story.”

Posted: 16 May 2018