Going viral: OUTBREAK weighs the risk of epidemics in a connected world

It took Magellan four years to circle the globe, but we can cross oceans in hours and reach the other side of the world in a day. Just as diseases such as smallpox and measles hitched a ride with early explorers to wreak havoc in the New World, globalization means that worldwide pandemics can be just an airplane flight away.

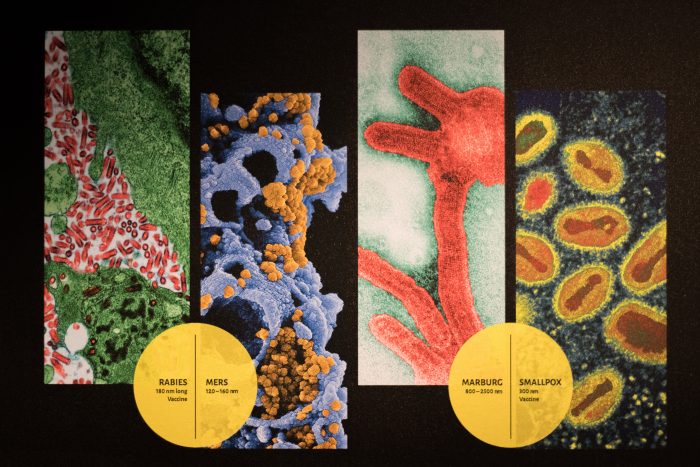

Microscopic images of some of the many diseases explored in “Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World,” a new exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History on view through 2021. (Photo by Jeremy Snyder / Smithsonian)

The irony was not lost on biological anthropologist Sabrina Sholts that she was home nursing a scratchy throat while discussing the new exhibit at National Museum of Natural History, “OUTBREAK: Epidemics in a Connected World.”

“I thought it was better that I not go to work and potentially infect my colleagues,” she said, with a chuckle.

OUTBREAK manages to meld easy, practical tips to contain viruses—such as staying home from work when you are ill and sneezing into the crook of your elbow to limit the spread of germs—with unsettling data about how pandemics begin and the threats they pose to global health. On a recent walk through the exhibit, which opened May 18, teen and adult visitors grappled with labels showing how SARS arrived in North America on an airplane while children ogled the oversized model of a mosquito and a giant fruit bat suspended from the ceiling (the exhibit looks closely at “zoonotic” viruses, or those that jump from animal to human).

Some animal species carry viruses that can also infect humans. These animals are reservoir hosts. Bats, rodents and non-human primates are the most common reservoirs in nature. This specimen of a wild fruit bat is on display in the new exhibition, “Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World,” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History through 2021. (Photo by James Di Loreto, Lucia RM Martino and Fred Cochard / Smithsonian)

“We recognize that our subject matter is complex and important and scary, but we also wanted to find ways to be effective in delivering these messages about how some infectious diseases spread,” said Sholts, the lead curator on OUTBREAK. “We don’t anticipate that people will immediately walk out of there and change their behavior, but we hope they will feel equipped and empowered to try and that we can raise their curiosity” about how viruses move around the world—sometimes in a matter of hours, typically via plane travel.

OUTBREAK considers how globalization and industrialization increase our exposure to viruses like avian influenza and Ebola—viruses many people had never heard of until they dominated the news with images of medical personnel in hazardous materials suits or cages full of chickens in a public market. The concept of One Health—that the health of the environment, animals and people must be considered holistically across myriad disciplines—is another key theme throughout the exhibit. No longer can the health of each be considered in a vacuum.

nimal health is linked to human health. Most viruses that infect humans are zoonotic—they originated in other animals. Influenza, Ebola, Zika, HIV and SARS are just a few of the over 800 known zoonotic viruses that cause human diseases. From industrial farms to live-animal markets, animals kept in crowded environments can easily spread influenza and other viruses. A crowded market scene featuring taxidermy specimens and models of wild animals provides a look at how spillover opportunities increase in scale and scope in an urban setting. In some countries, animals of different species are caged stacked or close together in live markets. Many of these animals never ordinarily meet in the wild. This creates opportunities for viruses to jump from one species to another. This market scene is on display in the new exhibition, “Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World,” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History through 2021. (Photo by James Di Loreto, Lucia RM Martin, Fred Cochard / Smithsonian)

Sholts trained as a biological anthropologist at University of California Santa Barbara, earning her doctorate in 2010. OUTBREAK—under development since 2014—is the first exhibit she has led.

Also known as physical anthropology, biological anthropology seeks to understand “the biological aspects of humanity by looking at the physical characteristics, functions, and uses of the body,” Sholts said. “I am particularly interested in the ways in which humans and the environment interact,” such as how the effect of pollutants in the environment impact people’s health over time.

Scientists can use remains and artifacts from past outbreaks to learn about modern ones. This man was diagnosed with influenza and tuburculosis at the time of death in 1929, but today scientists are studying his skull for new information about what other microbes and pathogens he harbored. The hardened plaque on his teeth preserves DNA that can be used to characterize the diverse community of his oral microbiome and explore its potential impacts on his health. This skull is on display in the new exhibition, “Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World,” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History through 2021. (Photo by James Di Loreto, Lucia RM Martino and Fred Cochard / Smithsonian)

In helping to develop OUTBREAK’S content, she had to find a way to simultaneously wear her scientist and educator hats to convey the information accurately yet manageably. When she moves through the hall discreetly listening in on visitors’ conversations, Sholts says she “feels relieved” that the messages seem to be getting through.

As a scientist, “I felt it would not be appropriate to put a rosy perspective on this global problem,” she said. Initially, “I had this idea that [we had to use fear] to drive understanding.” But Sholts and the rest of the team behind OUTBREAK—educators Robert Costello and Ashley Peery, exhibit designers Julia Louie and Shannon Willis, exhibit developer Sally Love, project manager Meg Rivers, writer Angela Roberts, and external science advisors Jon Epstein (EcoHealth Alliance) and Daniel Lucey (Georgetown University)—believe they managed to strike the proper balance between visitors feeling fearful and staying hopeful.

During World War I, more people died from the influenza pandemic (estimated 50 million–100 million) than from the war (estimated 17 million). Over half of the deaths from the pandemic virus were adults between the ages of 20 and 40, rather than the young children and elderly who typically die from the flu. Hospitals were quickly overwhelmed by the number of people sick from the flu and the secondary pneumonia cases that followed. Temporary, often overcrowded, infirmaries were created in auditoriums and public buildings to care for the sick. This photo of flu victims during World War I is on display in the new exhibition, “Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World,” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History through 2021. (Photo courtesy U.S. National Library of Medicine)

“We don’t sugar-coat the information, but we also give plenty of examples about what is succeeding” in terms of identifying, containing and halting outbreaks, she said.

Together with manager Audrey Chang and writer Laura Donnelly-Smith, some of the OUTBREAK team developed an innovative do-it-yourself version of the exhibit (OUTBREAK DIY) that people anywhere in the world (teachers, public health officials, museum workers, etc.) can access online to create a version of the exhibit suited to their own communities and resources. Printable, poster-sized panels of the exhibit’s content; multimedia videos and games; a style guide; and assorted other digital assets are available in multiple languages. To date, more than 50 venues from the American Center in New Delhi to the Global Health Institute at Harvard University to the Heureka Science Center in Helsinki, are working on their own versions of OUTBREAK.

A version of the DYI Outbreak exhibition on display in Thailand earlier this year. (Photo courtesy Sabrina Sholts)

Posted: 25 July 2018

-

Categories:

Collaboration , Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories , Natural History Museum , Science and Nature