How high did the Wright Brothers fly?

Kent Wang introduces us to Vince Massimini, a combat veteran and volunteer docent at the National Air and Space Museum.

The 1903 Wright Flyer is on display in the The Wright Brothers & The Invention of the Aerial Age exhibition at the National Air and Space Museum.

The National Air and Space Museum is home to the world’s greatest collection of vintage aircraft. These historic, beautiful, time machines inspire both the experienced pilot and the simply curious visitor with the courageous, optimistic spirit of American aviation.

The volunteer docents at Air and Space are as knowledgeable and enthusiastic as even the most aviation-obsessed visitor who has ever dreamed of soaring above the clouds. Take a tour and you’ll hear fascinating stories about the artifacts on display, and have your questions answered by a knowledgeable and engaging docent. Whether your tour is with an expert volunteer or a veteran pilot, you’ll explore the dramatic story of aviation, from the dawn of flight to the Space Age.

Vince Massimini is an aviation buff and talented aeronautics engineer and his knowledge of the planes is encyclopedic. There is a good chance you’ll find him in the gallery spending time the 1903 Wright Flyer—a signature Smithsonian object. (Photo by Kent Wang)

Once of those expert volunteer docents is Sebastian V. “Vince” Massimini, an aviation buff and talented aeronautics engineer, with a doctorate in operations research from The George Washington University. Vince is one of the many veteran pilots among NASM’s 300+ docents. He retired in 1990 as a Lt. Col. from the U.S. Marine Corps, where he flew the A4 Skyhawk, the T-39 Sabreliner, and other jet aircraft, including several hundred combat missions in Vietnam. His knowledge of the planes is encyclopedic and he has done the kind of flying most of us will only ever experience in adventure movies. He has been a docent since 2005, working every other Saturday at the Mall museum and leading school and VIP tours at the Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Va.

“It’s a perfect match for me,” Vince explains, “and it’s been wonderful–I love it. To me, the most enjoyable part of being a docent is getting to talk to the public. I try to make each tour educational, pleasant, and funny.”

He loves to speak with visitors about the aircraft on display and share stories with them. “You meet a lot of interesting people as a volunteer,” Vince says. Mrs. Massimini is also enthusiastic about his weekend volunteering: “He gets to talk and I don’t have to listen,” she says. (“Not that she listens to me anyway,” Vince says.)

Vince Massimini is one of many pilots among the 300-plus docents at the National Air and Space Museum. He often flies from his home at an airport on the Eastern Shore to College Park to take the Metro to NASM. College Park. Md. is also where the Wrights trained Army aviators in 1909.

For all the jokes about volunteering as a way to get a retired husband out of the house, docents at NASM receive no pay, have fixed time commitments and must undergo rigorous training. Being a docent is a volunteer job, but it requires the same drive, determination and dedication of a paid vocation and is a major commitment

Such expectations grow from an understanding of the docent’s power. Anyone who leads a guided tour or answers a visitor’s questions can have a profound effect on how people experience our museum. Docents are the face, the voice and the character of NASM and must be teachers as well as tour guides, and engaging as well as experienced.

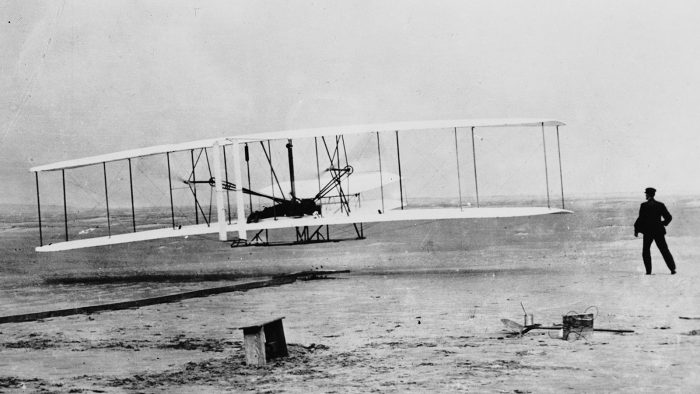

For docents, patience is not just a virtue, it is another requirement. One of the most popular exhibits in the museum is the gallery celebrating the Wright brothers. Docents are regularly asked about the 1903 Wright Flyer. “Is it real?” “How high did the Wright brothers fly?” “Were they really the first?” Often, docents must persuade argumentative visitors to the gallery that yes, the Wright brothers’ work led them to make the first controlled, sustained, powered flights on December 17, 1903 in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, not in Dayton, Ohio, as some maintain. “On December 17, 1903,” Vince says. “Orville Wright piloted the first powered airplane about 20 feet above a wind-swept beach in North Carolina. The flight lasted 12 seconds and covered 120 feet. Three more flights were made that day with Orville’s brother Wilbur piloting the record flight, lasting 59 seconds over a distance of 852 feet.”

1903 Wright Flyer First Flight, Kitty Hawk, N.C. With Orville Wright at the controls and Wilbur Wright mid-stride, right, the 1903 Wright Flyer makes its first flight, Dec. 17, 1903

According to Vince Massimini, a good docent is someone with a curious mind and a willingness to share. “It’s all about connections, and we really need to make those connections,” he says. “That’s why we focus on providing that connection between the visitors and what the Wright Flyer represents: the first powered, heavier-than-air machine to achieve controlled, sustained flight with a pilot aboard. We want to build relationships and that takes more than just saying, ‘We have wonderful exhibitions. Come see the great airplane’ and then walking away.”

Kent Wang has been a volunteer docent at the Air and Space Museum since 1997.

Posted: 20 September 2018

- Categories: