Mike Maslanka had a farm…

Americans spent almost $30 billion on pet food for Fido and Fluffy last year, but you can’t exactly run to the store for a half-ton of kibble when you have elephants to feed. John Barrat spent the day in Front Royal to see how the Zoo keeps its critters locavore.

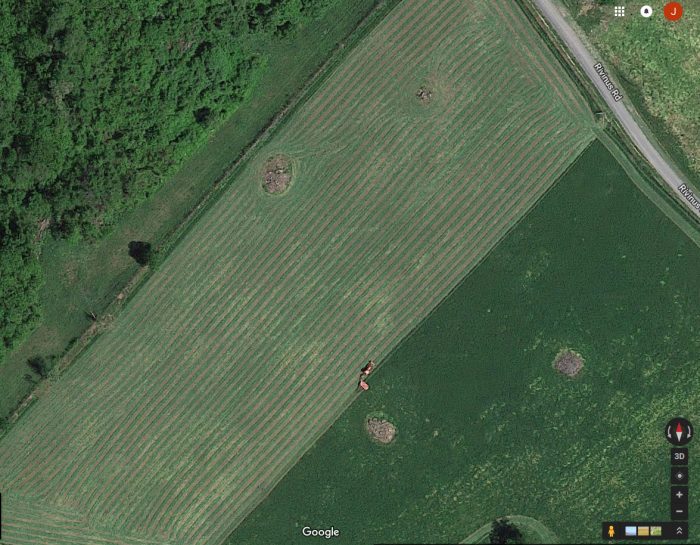

Windrows of warm season grass stretch across a high field at the Conservation Biology Institute near Front Royal, Virginia, waiting to be bailed. This grass is a four species mix, says Zoo nutritionist Mike Maslanka, consisting of switch grass, Indian grass, big blue stem and little blue stem grass. “We planted this warm season mix because it provides better habitat for a diversity of wildlife. It matures between 6-7 feet tall providing greater cover for bob whites and other wild ground nesting birds. (John Barrat photo)

Some of the most nutritious and beneficial food added to the diets of animals living at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington, D.C. and its Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Va., literally grows on trees. The “woody browse,” as zoo nutritionist Mike Maslanka calls it is, in fact, the trees themselves: leafy tree branches clipped from a variety of species native to the eastern United States. Elephants, gorillas, orangutans and other apes, and hoofed animals such as gazelles and oryx love it. Tree browse is what many animals eat naturally in the wild, and Maslanka makes sure they get it on a regular basis at the Zoo.

“Mulberry tends to be the favorite of most of the animals at the Zoo,” Maslanka says. “I have no idea why. The part of the plant that we target is the leaf, not the fruit. Mulberry leaves are high in fiber, lower in protein, and maybe a little bit lower in soluble carbohydrate content than the fruit,” which is only suitable as an occasional treat.

As nutritionists for the Zoo and SCBI, Maslanka, along with colleague Erin Kendrick, manage the diets of all the animals in the Zoo’s care.

From Sunday to Wednesday Maslanka works in Washington, beginning each day at 5:45 a.m. with the nutrition team in the Zoo Commissary. On Thursdays in spring, summer and fall, he’s out at the Conservation Biology Institute overseeing hay production and storage, a browse yard of young trees, a few plots of bamboo, a corn plot and other assorted projects, including leading a week-long practical zoo nutrition course for zoo professionals from around the world, through the Smithsonian-Mason School of Conservation.

From left, NZP Veterinary Resident Kailey Anderson and Smithsonian-Mason School of Conservation undergraduates Morgan, Peyton and Ana with freshly harvested bamboo. (Mike Maslanka photo)

They can’t leaf it alone

Inside a one-half-acre fenced-in yard at SCBI, Maslanka has established a small orchard of some 240 saplings that are harvested regularly for woody browse during spring, summer and fall. The trees, planted five years ago, are species the Zoo’s animals like the most and which grow the fastest: willow, birch, thorn-less honey locust, mulberry, and Norway maple.

Early on a Thursday morning in late August, for example, all of the branches on a 5-year-old willow in the browse yard were cut back hard and very close to the tree’s two-inch trunk. Some 200 pounds of tender shoots and leaves from the tree were bundled and sent by truck to the National Zoo where animals were munching on the fresh green vegetation a few hours after it had been cut.

Mike Maslanka stands next to a young honey locust tree growing inside the browse yard at the Conservation Biology Institute. Some 150 trees planted inside the yard represent species which are favored by Zoo animals and which grow the fastest. (Photo by John Barrat)

During months when trees are in leaf, the nutrition team cuts woody browse in the browse yard and elsewhere throughout the area several times a week. On other weekdays the team cuts locally grown bamboo, much of it grown on some 25 private properties whose owners have partnered with the Zoo to harvest bamboo.

In summer Maslanka and his team also freeze significant amounts of browse and bamboo in the Zoo Commissary’s big freezer to feed the animals during winter. “Some of the willow bundles we cut this morning—3 feet long and between 20-30 pounds—were put into big white bins and frozen,” he says. “In February or March when there isn’t a green thing to be found we will open those up those bins and have a bunch of green leaves that we can feed to the animals to provide them with a little bit of that fiber.”

The willow saplings cut in the browse yard—planted in a low area that gets a generous amount of water draining from a higher field—will spring back with enough new shoots to cut again next year.

Giant panda Tian Tian enjoys a favorite snack at the National Zoo. (Photo by Skip Brown)

The tall fence around the yard is a necessity, Maslanka points out. At the same time the saplings inside the yard were planted, a few were also planted outside the fence. “They’ve never been seen,” he says. Wild deer consumed the seedlings as soon as they sprouted a leaf.

A second plentiful source of woody browse Maslanka has tapped into comes from an ongoing partnership with the Zoo’s Horticulture Department, an office charged with maintaining the botanical aesthetics and health of vegetation on Zoo grounds. Maslanka shared a list of the tree species with the Horticulture team that can be eaten by the Zoo’s residents and they give Maslanka advance notice when they will be removing a large tree or doing significant trimming.

The Horticulture Department also has access to heavy equipment—a crane, front end loader, and other vehicles—that can handle big trees. “When we can place a tree with a two-foot-diameter trunk into the elephant yard, that’s fantastic,” Maslanka says.

Large trees and branches provide more diet complexity, interest and effort for the elephants than their standard diet. First they eat the leaves, then the finer ends of the branches, breaking them off with their trunks, and then they break up and chew the thicker parts of the branches. Eventually they strip the bark off of the trunk and consume as much of it as they can. It’s a gradual process that enhances the elephants’ nutritional welfare.

The branches of this young willow tree growing inside a fenced yard at the Conservation Biology Institute were cut back hard and taken in to the National Zoo to be eaten by some of the resident animals at the National Zoo. (John Barrat photo)

This type of foraging is ideal for an elephant, Maslanka explains, as it slows down the rate that which food enters and passes through their gastrointestinal tract. Working on a tree requires the use of different muscles; attention is required to take the tree apart; and a large tree usually provides enough room for a number of animals to work on it at one time, creating prolonged social interaction. “It’s a more natural situation,” Maslanka says.

Making hay while the suns shines

When in season, fresh alfalfa is another healthy dietary supplement Maslanka sends regularly from Front Royal to animals at the Zoo. He will ride up to the alfalfa field on the Institute’s grounds early on a summer morning and using hand clippers, fill a cooler with fresh alfalfa which is put on ice and sent to the Zoo.

“The gorillas and orangutans really like fresh alfalfa when it’s in flower. We can cut it here and it can be in the mouth of an ape at the Zoo in three and a-half hours,” Maslanka says. That’s probably fresher than what you’ll find at your lunchtime salad bar.

However, most of the alfalfa and grass forage grown in Front Royal arrives at the Zoo in dried bales throughout the year.

“Alfalfa is a legume, which means the hay has higher protein and calcium with about the same fiber as grass hay, “ Maslanka says.

“There are not a lot of animals that need legume hay at either facility, because it tends to be on the rich side for most, but we’ve got tufted deer, Eld’s deer, and some delicate gazelles, such as the damas, that benefit from alfalfa.

“One of the things that separates us from every other Zoo in the country is we can grow all of our hay here on campus,” Maslanka continues. ““Because of this we can tailor crops we are growing to what our animals need. For example, if we need hay with a little bit higher protein, we can mow a field early. Or, if we need hay with a bit higher fiber content, we can allow a field to fully mature before we mow it.”

This Google Earth image shows alfalfa being cut in windrows in preparation for bailing at the Smithsonian’s Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Virginia.

Two barns at the Conservation Biology Institute were packed to the rafters with grass hay and alfalfa bales by mid-summer. Most of the bales will eventually go downtown to the Zoo, Maslanka says, but the hay is also used for the animals living on the Conservation Biology Institute grounds.

Hay production at SCBI is done by an experienced local farmer. “We manage the contractor and he helps manage the land for us, making all the hay. It’s a 24/7 operation when it is time to make hay,” Maslanka says. “The contractor and his team have worked on this property for a long time, they know the place well, care about our land and our animals immensely, and do an excellent job for the good of our animals and operation.”

Mike Maslanka carries an armload of fresh bamboo to the giant pandas at the Zoo. (Photo courtesy Smithsonian’s National Zoo)

All land management activities, including hay, browse, and bamboo production at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute fit into an overall land use plan that guides the entire facility. The land-use committee vets all land management activities to ensure the “greater good of the property is kept in mind,” Maslanka says. “The land use committee works through many proposals and reviews their applicability given what we do here, and how if fits into the overall land-use plan, and forage production, whether hay, bamboo, or browse, is part of that.”

A corn-ucopia of deliciousness

On a hill bordered by a tall fence, Maslanka has planted what he calls a “meager” plot of corn. “We’re not after the ears, we’re after the plant,” he points out.

A few years ago at a conference in Scotland, zoo keepers from Austria asked Maslanka and other Zoo staff if they had ever tried feeding corn stalks to the National Zoo’s giant pandas. It is just grass and pandas eat bamboo (grass), they said. Why not try it?

“We gave them corn stalks when we returned and the pandas love it, actually love it,” Maslanka says. “The first time they tried it was in summer and we put it down in their outdoor exhibit area. To the delight of our visitors, the pandas sat down there and interacted with it, peeled it and ate it for hours. Before, on hot days, all they wanted was to be inside in the air conditioning.”

On a hot day in late August Mike Maslanka inspects a small plot of corn planted on a hill on the northern border of the Conservation Biology Institute near Front Royal, Virginia. The corn stalks are cut fresh and fed to giant pandas, elephants and other animals at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. (Photo by John Barrat)

Zoo animals aren’t the only ones who enjoy SCBI’s bounty. Here is the cornfield the morning after some local bears had a feast. (Photo by Mike Maslanka)

As Maslanka and others were to learn, the pandas don’t seem to like the corn stalks until the corn plants set their ears. Elephants and a variety of other animals at the Zoo also prefer the stalks only after the ears have set. “We don’t give them the ears but pull them off and just give them the stalk,” Maslanka says. Once mature, the ears are put to good use in the Zoo’s Commissary.

Despite the small size of the corn plot, “it is fantastic for our needs,” Maslanka says. “This morning we probably sent a couple of hundred pounds of corn stalks back to the Zoo, in addition to the browse we sent back.”

Being able to manage some of the natural resources available to us in Front Royal is a great benefit to the animals at both facilities. It is one of the unique ways in which we constantly strive to best address the nutritional needs and welfare of our animals every day.

From left, Mike Kirby, Chris Stout (NZP Department of Nutrition Science) and Kailey Anderson with a truckload of bamboo and woody browse destined for the Zoo. (Mike Maslanka photo)

Posted: 18 October 2018

-

Categories:

Feature Stories , Science and Nature , Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute