Armistice and peace: Victory letters from WWI

One hundred years ago, November 11, 1918, world leaders signed the Armistice, marking the end of World War I. On that day, many American soldiers serving abroad were instructed to write victory letters to their fathers. Elizabeth Borja takes a look at the correspondence between a father and son that illustrates a different understanding between home and the front, armistice and peace.

Harvey Dunn’s painting “On the Wire” from the A.E.F. Collection of the National Museum of American History.

Letters home from the front reveal the personal side of wars. On Armistice Day, November 11, 1918, marking the end of World War I, many American soliders serving abroad were instructed to write victory letters to their fathers. As we move towards the celebration of the 100th anniversary of Armistice Day, a pair of victory letters from France and Connecticut illustrate a different understanding between home and the front, armistice and peace.

When the United States entered the war in 1917, Harold F. Pierce was a fellow in physiology at Harvard Medical School. Pierce initially contributed to the war cause working with the Bureau of Mines on the effects of poison gas and the improvement of gas masks. He then accepted a commission as a Captain in the Sanitary Corps under the Surgeon General.

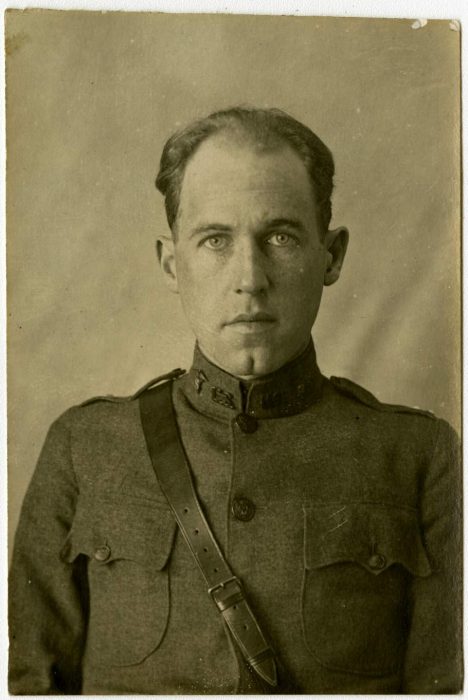

Portrait of Harold Fisher Pierce, in uniform, taken in Issoudun, France, September 27, 1918. Credit: National Air and Space Museum Archives, NASM 9A12103.

Pierce began his service as a flight surgeon at the Medical Research Laboratory at Hazelhurst Field in Mineola, New York, under the command of Col. William H. Wilmer. Given that airplanes were still a relatively new technology, the field of aviation medicine was also brand new, as doctors rushed to understand how flight affected human physiology.

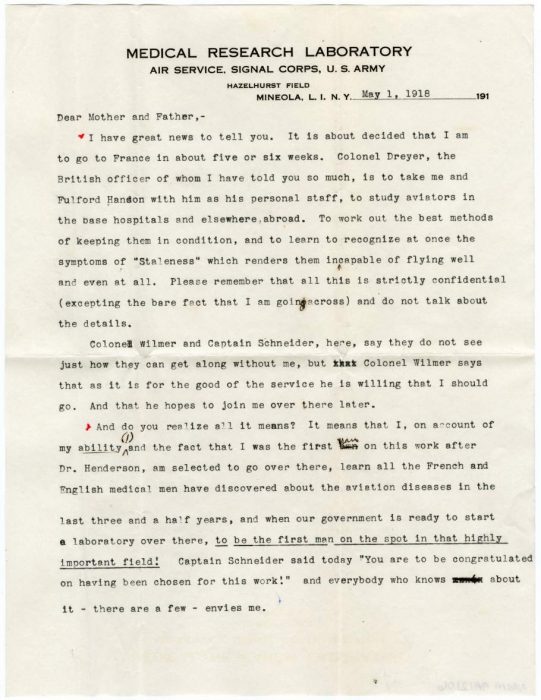

In May 1918, Pierce wrote home that he was to be a member of the first group from the Medical Research Laboratory to travel to France to establish research facilities there. His excitement leaps off the page: “[To] be the first man on the spot in that highly important field!”

Page 1 of a letter from Harold F. Pierce to his parents, dated May 1, 1918. Sent from the Medical Research Laboratory at Hazelhurst Field, New York, Pierce tells his parents he is being sent to France and discusses the importance of the work he will do there. Credit: National Air and Space Museum Archives, NASM 9A12106

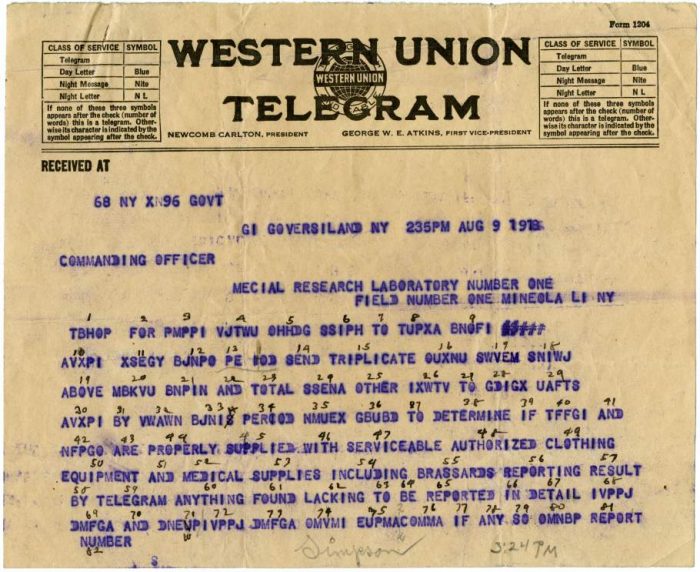

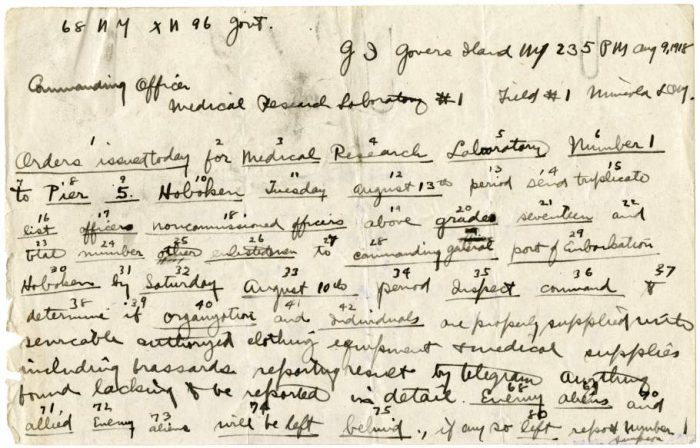

Subsequent letters reveal Pierce’s frustration with the long, bureaucratic process in establishing this overseas post. He made list upon list of supplies necessary for the new facility. An August 9 telegram issuing orders to the Medical Research Laboratory regarding their upcoming transport of people and supplies to France highlights the importance of this undertaking. It was written in code!

Coded telegram dated August 9, 1918 to the Commanding Officer, Medical Research Laboratory at Hazelhurst Field, New York. Credit: National Air and Space Museum Archives, NASM 9A12107

Translation of coded telegram dated August 9, 1918, to the Commanding Officer, Medical Research Laboratory at Hazelhurst Field, New York. Telegram describes necessary arrangements to be made for setting up a medical research laboratory in France. Credit: National Air and Space Museum Archives, NASM 9A12108

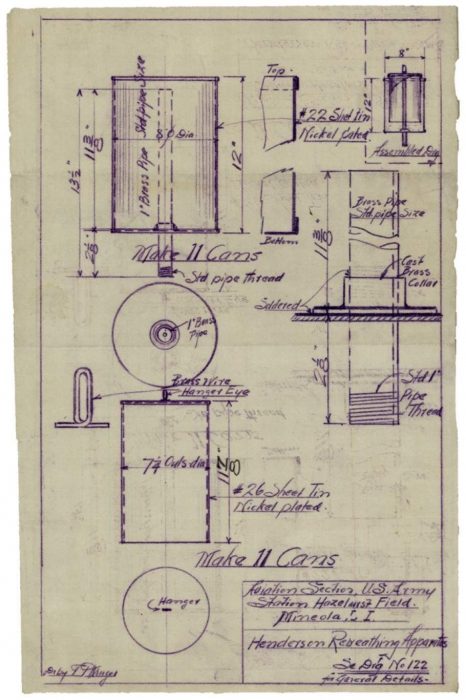

Pierce finally set foot in France in late August 1918. He continued his work on a rebreathing apparatus, based on his research from the Bureau of Mines and Hazelhurst. The Henderson-Pierce rebreathing apparatus (named after Pierce and Yale physiologist Yandell Henderson) tested an aviator’s ability to withstand low oxygen, particularly those conditions at high altitudes.

Engineering Drawing for Henderson Rebreathing Apparatus [Henderson-Pierce Rebreathing Apparatus], Aviation Section (US Army). Credit: National Air and Space Museum Archives, NASM DrwItm-0076418

U.S. Army Air Service personnel testing a rebreathing device at the medical research laboratory at Tours Aerodrome, Second Air Instructional Center (2d AIC), American Expeditionary Forces, 1918. Credit: National Air and Space Museum Archives, NASM 9A11930

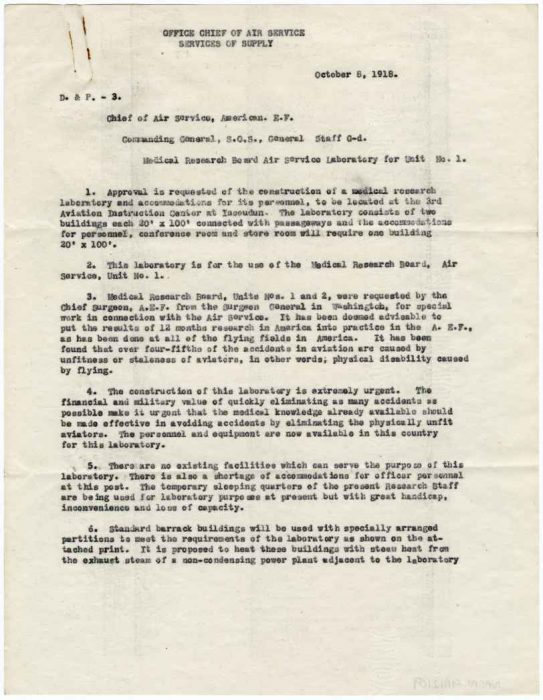

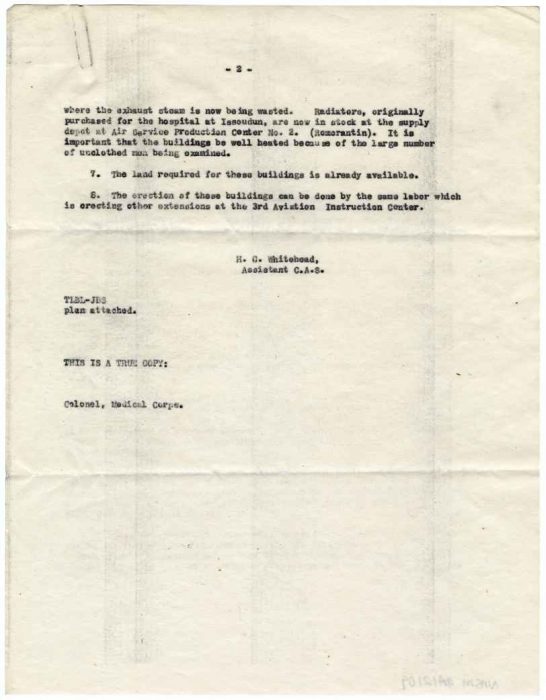

Pierce and his colleagues established facilities at the Second Aviation Instruction Center at Tours, France, and the Third Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun, France. As late as October 1918, the Air Service was working to approve and construct these research centers.

Page one of two-page memo, dated October 8, 1918, from H.C. Whitehead, Assistant Chief of Air Supply, to the Commanding General, Services of Supply, requesting permission to construct a medical research laboratory at Issoudun, France. Credit: National Air and Space Museum Archives, NASM 9A12109

Page two of two-page memo, dated October 8, 1918, from H.C. Whitehead, Assistant Chief of Air Supply, to the Commanding General, Services of Supply, requesting permission to construct a medical research laboratory at Issoudun, France. Credit: National Air and Space Museum Archives, NASM 9A12109

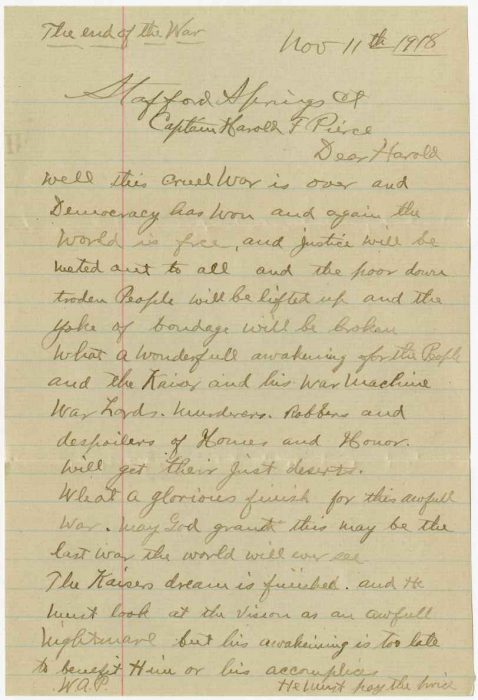

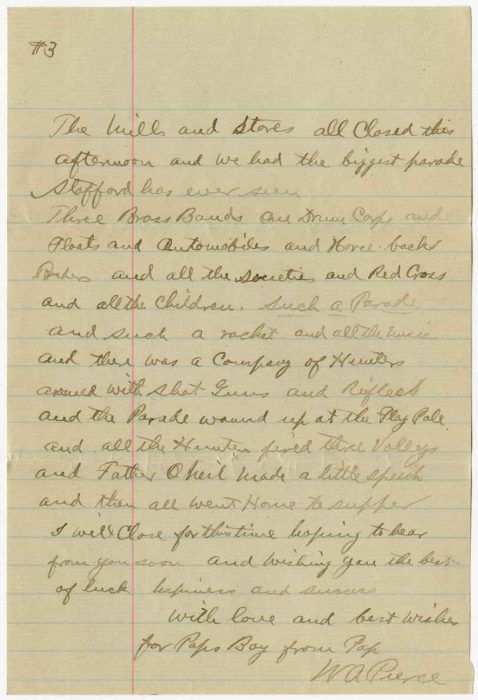

Armistice came on November 11, 1918. The home front was jubilant. Pierce’s father in Connecticut wrote a victory letter to his son as soon as he heard the news: “Well, this cruel war is over and Democracy has won and again the World is free, and justice will be meted out to all and the poor down-trodden people will be lifted and the yoke of bondage will be broken…May God grant this may be the last war the world will ever see.”

Page 1 of W.A. Pierce’s “victory letter” to his son, Harold F. Pierce (serving in France), dated November 11, 2018. Credit: National Air and Space Museum Archives, NASM 9A12105

Page 3 of W.A. Pierce’s “victory letter” to his son, Harold F. Pierce (serving in France), dated November 11, 2018. Credit: National Air and Space Museum Archives, NASM 9A12105

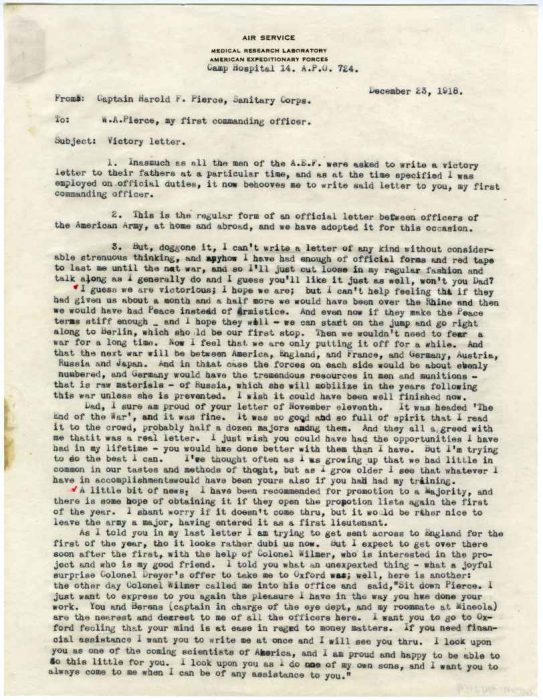

Pierce’s response on December 23 was much more tempered. Touchingly, he addressed the letter to his father, “my first commanding officer.” He began formally that the men of the American Expeditionary Forces were instructed to write a “victory letter to their fathers.” By paragraph three, “doggone it,” he gave up on formality.

Pierce’s next words are chilling: “I guess we are victorious; I hope we are; but I can’t help feeling that if they had given us about a month and a half more we would have been over the Rhine and then we would have had Peace instead of Armistice. And even now if they make the peace terms stiff enough – and I hope they will – we can start on the jump and go right along to Berlin, which should be our first stop. Then we wouldn’t fear war for a long time. Now I feel we are only putting it off for a while. And that the next war will be between America, England, and France, and Germany, Austria, Russia and Japan. And in that case the forces on each side would be about evenly numbered, and Germany would have the tremendous resources in men and munitions – that is raw materials – of Russia, which she will mobilize in the years following this war unless she is prevented. I wish it could have been well finished now.”

Page 1 of Harold Fisher Pierce’s “victory letter” to his father, sent from France and dated December 23, 1918. Credit: National Air and Space Museum Archives, NASM 9A12104

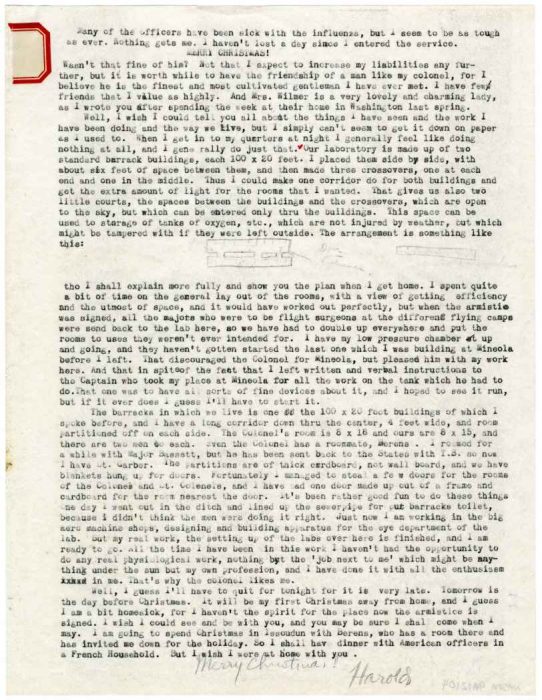

Page 2 of Harold Fisher Pierce’s “victory letter” to his father, sent from France and dated December 23, 1918. Credit: National Air and Space Museum Archives, NASM 9A12104

Pierce’s war ended with an invitation to Oxford University to continue his studies and work with rebreathing equipment as a tutor and demonstrator of physiology. He even worked with British Mount Everest expeditions. He returned to the United States in 1922 to serve as Associate Physiologist at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University, earning his Ph.D. in 1927. He then spent eight years at the Wilmer Institute at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, having served in WWI with William H. Wilmer, the institute’s founder. Pierce served as a consultant for the design of the capsule for the Explorer II manned high-altitude balloon launch with Captain Albert W. Stevens, maintaining a friendship with Stevens and his wife, Ruth, long after the event.

In 1941, the United States entered World War II, the war that Pierce had feared “only putting…off for a while.” Pierce returned to service as a flight surgeon and altitude physiologist for the United States Army Air Forces at the School of Aviation Medicine (the new name for the Medical Research Laboratory) at Randolph Field, Texas. In 1945, he transferred to the Avon Old Farms Convalescent Hospital in his home state of Connecticut. After World War II, he served as a medical director of the Connecticut State Welfare Department and as a consultant in aero-physiology at Hartford Hospital until retiring in 1960.

The Harold F. Pierce Aviation Medicine Collection at the National Air and Space Museum documents Pierce’s pioneering career in aviation medicine, covering his work with the Bureau of Mines, WWI, the Wilmer Eye Institute, Explorer II, and WWII. The three cubic feet of material include correspondence, military records, photographs, certificates, technical drawings, and news clippings. His personal letters home during WWI are particularly enlightening regarding camp life in France and the birth of aviation medicine.

This post by Elizabeth Borja of the National Air and Space Museum’s Archives Division was originally published by the museum’ blog.

Posted: 11 November 2018

-

Categories:

Air and Space Museum , Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories , History and Culture